Let’s just say your mother is a potter, an accomplished potter, a demanding potter. At the end of her life she started work on a new approach and made some progress. But then she took ill and joined the ceramic guild in the sky. Her last request? Destroy that last pot. What would you do? Honor her request by breaking it into a thousand pieces or honor her life’s work by keeping it?

Let’s just say your mother is a potter, an accomplished potter, a demanding potter. At the end of her life she started work on a new approach and made some progress. But then she took ill and joined the ceramic guild in the sky. Her last request? Destroy that last pot. What would you do? Honor her request by breaking it into a thousand pieces or honor her life’s work by keeping it?

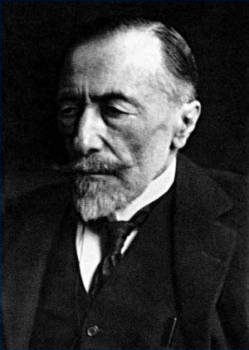

That’s the dilemma faced by Dmitri Nabokov, son of Vladimir. To destroy his father’s last manuscript, actually the 138 index cards on which was assembling his last novel in typical Nabokovian fashion, or keep it and perhaps publish it. Perhaps you already know about this, yes? It’s made the mainstream media and the literary blogs, and the New York Times had an interview with Dmitri on Sunday.

So, should Dmitri burn The Original of Laura as Vladimir asked, light index card number one (with what, a kitchen match? a lighter made especially for the occasion? toss it into a good wood fire?) and watch the stack of them turn to ash? That’s what he said he wanted. Oops. Did you catch that “he said”? That’s a crack in the door through which Dmitri inserted his foot. Because what did Vladimir really want? Because sometimes he said things that he didn’t mean. We all do. And what we say can run counter to our deepest desire. And the request seems like such a gesture, a Romantic gesture. Dmitri knew his father (he even visited him recently to help him resolve the dilemma!). And he has decided to publish Laura. Scholars and the literary public rejoice!

Personally, I imagine that Vladimir meant what he said: Burn the damn thing. It’s caused me nothing but trouble. I keep getting sick. It’s not done. It’s not good. Yet. (I give him the “yet”.) It will be a weight off my shoulders, and I need to be unencumbered as I pass across the River Styx. Actually, I ‘m sure he wouldn’t say “weight off my shoulders” and I don’t know what his views on the afterworld are. But you get the idea. It’s a reasonable point of view. Dmitri defied his father.

Continue reading Scatter considers the Nabokov Dilemma