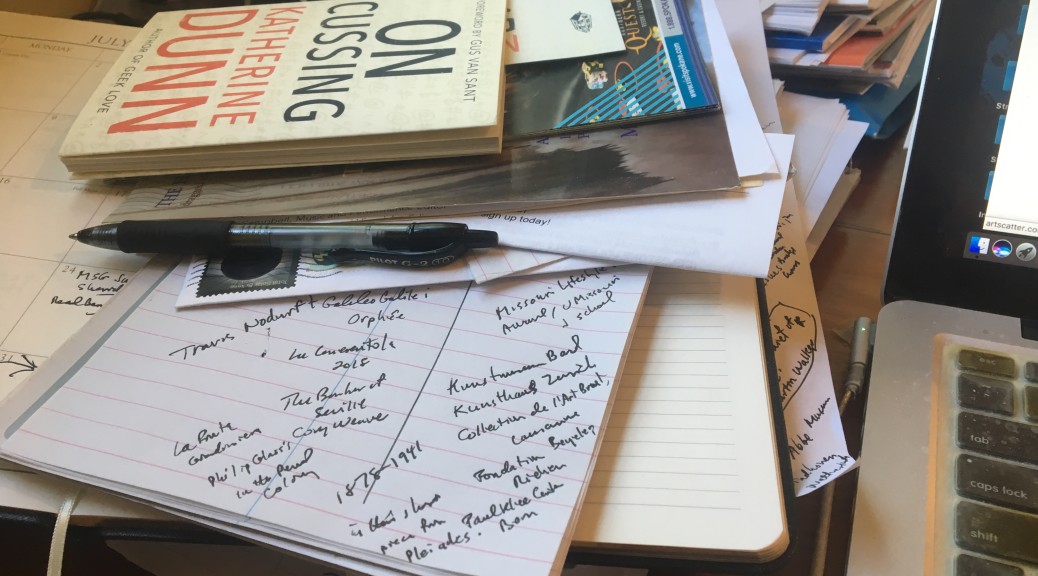

STACKS OF NOTEBOOKS TEETERING a foot and a half high. Scraps of paper torn from here and there, covered in cryptic and often indecipherable scrawls: old envelopes and junk mail, stray printouts, performance programs, grocery lists flipped to the other side. In our brave new electronic age, odd passages struck by thumb and stored in the Notes app of our smart phones. Strange names and phone numbers. Possibly important dates, if only you could remember what they’re for. Vital phrases and dead ends. Whole paragraphs out of the blue, scribbled in haste before they can vanish into the mist.

Writing is a messy enterprise, a stumble toward clarity through a thicket of confusion. The writer jots down notes amid the chaos, little clues to mark a path toward a destination he can’t quite see and whose appearance, if ever he discovers it, might easily arrive as an utter surprise, not at all like whatever it was he envisioned when he set out.

It’s possible, of course, that some writer somewhere sits down to keyboard or notepad at a desk of virginal cleanness and simply composes, fresh, from brain to fingers, in a smooth spontaneous stream. I have not met this person. My own writing environment is a haphazardly orchestrated disaster zone of unfinished projects, dubious side trips, and cryptic hints of ideas that, having been jotted onto paper or screen, have joined the daunting pile of faint yet hopeful possibilities. Now, where is that thing that I wrote down three weeks ago and suddenly realize might fit into the blank spot on the page I’m working on today? What was it, again? Let me just see if I can track it down. Somehow, this organizational calamity comforts me and spurs me on.

A CERTAIN CAPITULATION TO THE WHIMS of chance and circumstance is necessary, it seems to me, to the delivery of a healthy tale. I don’t mean to suggest that writing is some sort of holy mystical process, and that the writer is merely the conduit for messages funneled from the gods (although religions have been fortified by this very belief). Far from it. A writer has to have a clear sense of what her subject is, and how she wants to begin exploring it, and where she hopes it might lead. She’ll want to be specific, and to make connections both to other, parallel specifics and to broader cultural points. Even if she isn’t a formal outliner, an outline will be forming in her head, and shifting as she gains new information. Much of writing is very conscious, goal-oriented, and precise, like mapping a terrain: How do I get from this place to that, without wandering unduly in the wilderness? Yet the subconscious is along on this journey, too, and often takes the lead. It’s carrying out its labor belowground, working the shortcuts and alternate connections we call intuition, using other logics, trying out unanticipated shapes and seeing how they fit. This isn’t magic. It’s just another way the brain works, and one of the writer’s primary tasks is to figure out, when her subterranean worker emerges from its tunnel with its fresh ideas, how to incorporate them into a story’s existing framework – or even, sometimes, to let them redesign the framework from scratch.

These two ways of thinking, the analytical and the improvisational, are common, I suspect, in all creative enterprises: painting and sculpting, composing and performing music, designing houses or everyday products, engineering, higher mathematics, cooking, teaching. And in each of these there are ideas that come to bat and just strike out. This isn’t a bad thing. It might even be necessary.

KILL YOUR BABIES, editors advise, meaning, sacrifice those precious passages that are dear to you for their witticism or elegance or turn of phrase but that call undue attention to themselves, getting in the way of your overall structure and argument. What editors and writing teachers tell you less often is that many of your babies will die a natural death – ideas that pop up and demand your attention and then, for whatever reason, go nowhere. Maybe their timing isn’t right. Maybe they don’t connect. Maybe they’re just dead ends. You still need to look at them, and give them a chance, and then, if they don’t work out, abandon them with no regrets. Not all notes are created equal.

About those notes: When do you take them, and why, and what use are they? At a New York performance I once sat next to a nationally prominent writer who scribbled so assiduously into her notebook that it seemed she couldn’t possibly be allowing herself the opportunity to let the performance itself sink in: To analyze, mustn’t one experience first? People often ask me whether I take notes during a performance. I took a lot when I was beginning: lines of dialogue, notes on lighting or costuming, anything and everything that struck me as possibly important. Now I take very few, and often just a word or two to remind me of a point when I’m writing later. Interviewing someone is different. I want to catch not just the actualities of the conversation but also the nuances of what’s being said, along with impressions of the surroundings, the topics, and the person. That can wind up filling several pages with notes that become, in the writing process, pieces of a puzzle.

Other notes, of course, serve their immediate purposes and are done: the spelling of a name, an address, the title of a painting. And yet there they are, in the notebook, ghosts in the machine.

THE OTHER DAY I REALIZED that the Notes app on my phone was cluttered with a few years’ worth of messages to myself, and decided it was long past time to clear them out. Shopping lists, appointment reminders: gone gone gone. But buried among them were quite a few writer’s notes – quick thoughts and even extended passages that had struck me at odd times and places and had seemed so important that I typed them on my smart phone’s tiny keyboard to keep them available for further use. What use, if any, did they eventually come to? Did they live or die? If they died alone and forgotten, was there still a purpose in recording them? What might they still mean to the larger questions of how a person writes?

Here are a few, as a typed them in, followed by their fates as I remember them. Some became parts of stories. Some went nowhere. But even going nowhere they are part of the picture, insights into the writing process, which necessarily says both yes and no. Notes, after all, are what writers do:

*

THE NOTE:

“Rolling, rocking, rollicking on the train out of New York toward New Haven. It’s a forward thrust with a sideward sway, a reminder of why train images turn up in so many kinds of music, of why music and trains get along so well, from Western to folk to blues to jazz. A honk, a thump, a snare roll rhythm down the line. Music is motion. When it stops, it stops so it can start again.”

THE RESPONSE:

Written on the train, somewhere east of Grand Central Station. Well, yes – I’ve always liked the rhythm of a train. But unlike the New Haven Line, this scrawl went nowhere: The tracks ran out. Best leave this sort of thing to Jimmie Rodgers the Singing Brakeman and other songwriters and guitar players who do it so well.

*

THE NOTE:

“… which is too bad, because Katherine had a voice like sour mash and cigarette ash, deep and funky and magnetic. The effect was like rolling over train tracks on the Coast Starlight or Empire Builder: a little jumpy and clattery but also warm and soothing, with a hum of amusement and a cadence to match the rhythm of the passing miles.”

THE RESPONSE:

On the other hand, sometimes a train metaphor actually crosses the Continental Divide. Stories take time to ripen, and often they do their ripening out of sight, while you’re busy doing other things. The makings of this description must’ve been tumbling around in the back of my brain, chugging away on their own time to formulate themselves into words, and when they forced their way to my attention I plugged them into my phone before they flitted off again, not knowing how they’d fit with other sentences that hadn’t been written yet. They ended up in a short piece – an item in a weekly column – about the late, great Portland writer Katherine Dunn, author of the novel Geek Love, on the occasion of a coming-out party for the publication of her very short and wryly funny posthumous book On Cussing. I must’ve had something in mind when I started typing on my phone, because I began mid-sentence, complete with ellipses to indicate a missing lead-in, which eventually got written. Interestingly, the beginning of the column was about a concert by the great tap dancer Savion Glover, of whom I wrote that watching his performance “was a bit like watching and listening to the Midnight Special at full throttle, barreling down the track.” Take a note: I do like trains.

*

THE NOTE:

“It took me a while to realize that the past is always present, lurking, ghosting, stealthily shaping what we think of as the new.

“I was not enamored of history as it was mostly taught, a dry and pedantic recitation of wars and rulers and dates, and so as a child I didn’t much read those spiced-up, tamped-down, breathless books about capital-H Heroes in their formative years. Something with sly humor, like the mouse-narrated “Ben and Me,” yes — but I knew it was a fiction of a different and more honest sort than those tales of the boyhood heroics of men who, mostly, grew up to be politicians. I sensed on the authors’ part a kind of condescending manipulation, not to mention a narrative unimaginativeness, and I shied away.

“I wish I’d known of …”

THE RESPONSE:

I wish I’d known of what? For the life of me, I have no idea. Did I have a particular essay in mind? What spurred this thought? And why did it end up abandoned, going nowhere at all? That said, this short passage does spell out some themes in my writing and my life: that the past is very present in our lives and culture, shaping what we think and do, and that to ignore it is a devastating mistake; that the past must be assessed honestly, avoiding the urge to mythologize, or, when looking at existing myths, to try to understand why they take the shape they do. If this particular passage didn’t come to fruition, its ideas are scattered across much of what I write.

*

THE NOTE:

“It is a matter of confusion and distress that one wishes not to spend all or even a majority of one’s waking hours thinking about politics (the greatest freedom in the land of the free is the freedom to ignore the public sphere and simply lead a private life) and yet it is the purloining of public life by the privateers of business and their political handmaidens that brings to bear the intrusion of the public into our every private thought. This is the curse of the rogue corporocity and its faithful lieutenant, the theocracy-in-waiting: there is no escaping it; no refuge or retreat. To regain our privacy we must give it up, and join the fray.”

THE RESPONSE:

All true, in my assessment of the state of our current culture and politics, but thickly stated, a bit badgering, as much a complaint as an assessment. What illumination might be added? Where might one go from here that hasn’t already been said, and better? One states a problem. Then one must posit a solution, or at least some avenues of exploration.

*

THE NOTE:

Chekhov of the suburbs.

“Maybe it’s not a life of quiet desperation, after all. Maybe they just think it is, but it’s something else entirely. Maybe they’ve been happy all along, wandering through life thwarted and morose, because that, when it comes right down to it, is the way they prefer things. Or maybe that’s not it at all: maybe life just happens, and you accept it or you don’t. Maybe happiness is a rare visitation, a gift, a moment when the stars collude and you realize who you are and how you fit and just accept it, and then the moment floats away but not before it’s left you with enough hope and light to make it through the stumbling morass of mere reality, of life happening and crumbling, until the visitation comes again. Maybe it’s just paying attention, just reaching out instead of in. Maybe happiness is love, and you found it long ago and then forgot, but there it’s been all that time, in front of you, beside you, only waiting. Maybe that’s the real reality. Might it be?

“Someone’s ill, and maybe someone else, and it’s tough to face but maybe it’s not going to get better, and that’s the thing: life is terminal, and maybe that’s not its point but that’s it’s reality, and in the meantime, what are you going to do?

“Theater is tragedy. Sometimes life is just a situation comedy that deepens and takes on shadings and becomes real. Or maybe that’s what theater does. Who knows?”

THE RESPONSE:

This is a highly unusual note in that it’s both relatively lengthy and it ended up being used, not as a rough passage to be reworked or mined but almost exactly as written (a few words are added, and the next-to-last paragraph is moved up), as the conclusion to a review of Third Rail Repertory Theatre’s 2015 production of Will Eno’s play The Realistic Joneses. It’s a rare case of a note becoming not just a reminder or a detail or a statement of a theme but a crucial part of the compositional process: In this note, the improvisation and the structure fused, and, as the body of the essay hadn’t yet been begun, set the tone and structure of the entire review. Unusually, I began at the end and worked my way back to the beginning. Have I mentioned, writing is a funny game?