“Surrealism and Painting” Max Ernst (1942)

I celebrated Scatter birthday by revisiting the Menil Collection in Houston, the source for my posts last year on the extraordinary art collection amassed by two Europeans, John and Dominique de Menil, who brought their oil business and modern art collection to America at the beginning of World War II. Located in a park-like complex that is surrounded by a neighborhood of modest bungalows, the Collection of more than 16,000 pieces includes a gallery devoted to Surrealism and offers individual shows, such as last year’s idiosyncratic “How Artist’s Draw,” curated by Bernice Rose.

Last week I spent two days at the Menil, most of it wandering through the gallery housing “Max Ernst in the Garden of Nymph Ancolie,†then in its last two days. The show focused mostly on the evolution of Max Ernst’s themes and motifs between the two World Wars, culminating with a view of a huge (nearly 14 x 18 feet) oil on plaster mural he produced for a Zurich nightclub, which has been transferred to plywood panels and restored.

Surrealism and Ernst are the Collection’s core. The de Menils met Max Ernst (1891-1976) in Europe before World War II and became unalterably infected with his Surrealist vision. The show included a new film about the installation of a 1973 Ernst exhibit at nearby Rice University, supervised by Dominique de Menil. The film, “Max Ernst Hanging,†was produced by Francois de Menil and John de Menil, son and grandson of the de Menils, and features vintage black and white footage of Dominique de Menil organizing the show, as well as incredible coverage of Ernst, then in his early eighties, walking through the space while the exhibit is being hung, looking at pieces he hadn’t seen in years, and then mingling with Houston’s art patrons during the opening. Many of the pieces in the 1973 exhibit were on view in the current show. (Olga’s Gallery is a great place to get a quick look at a cross-section of Ernst’s work.) The experience sparked a few reflections.

Surrealism and Ernst are the Collection’s core. The de Menils met Max Ernst (1891-1976) in Europe before World War II and became unalterably infected with his Surrealist vision. The show included a new film about the installation of a 1973 Ernst exhibit at nearby Rice University, supervised by Dominique de Menil. The film, “Max Ernst Hanging,†was produced by Francois de Menil and John de Menil, son and grandson of the de Menils, and features vintage black and white footage of Dominique de Menil organizing the show, as well as incredible coverage of Ernst, then in his early eighties, walking through the space while the exhibit is being hung, looking at pieces he hadn’t seen in years, and then mingling with Houston’s art patrons during the opening. Many of the pieces in the 1973 exhibit were on view in the current show. (Olga’s Gallery is a great place to get a quick look at a cross-section of Ernst’s work.) The experience sparked a few reflections.

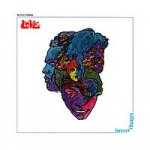

“What kind of bird are you?†(A question from a patron at the 1973 opening in “Max Ernst Hanging.â€) A good question. Ernst and his work are filled with birds, so much so that the painter adopted an alter-ego, “Loplop,†a phoenix-like, anthropomorphic bird that is at once image and observer in his work, and appeared again and again in his paintings and sculpture. Birds that are cut-out drawings or photographs used in collages, dotted-line or cartoonish birds in cages lightly painted on the surface of otherwise detailed paintings, sculptured birds, and strange biomorphic creatures that share bird and human and even vegetal and insect forms and characteristics. At times the birds seem trapped and isolated, at other times spiritual and free, and then, as in, “Surrealism and Painting,†shown above, the bird-human form – is it one figure or are there three? – suggesting an almost sentimental notion of family. It is serene, secure and a bit claustrophobic. But birds. Birds everywhere.

Continue reading What kind of bird are you? Looking at Max Ernst

Cousin Rick, a far-flung Scatter-friend, writes from Paris. Writes! On writing paper, with hand-formed, fully-formed letters and elegant sentences. Like tooled leather, it seems to me.

Cousin Rick, a far-flung Scatter-friend, writes from Paris. Writes! On writing paper, with hand-formed, fully-formed letters and elegant sentences. Like tooled leather, it seems to me.  “We change what we remember, then it changes us, and so on, until we both fade together, our memories and ourselves. Something like that.†This is Salman Rushdie on the way our lives intertwine with the history of rock ‘n’ roll. The Ground Beneath Her Feet (1999 ) is a novel about Ormus and Vina, Indians raised in Bombay, who become the first couple of international rock. Propelled by Ormus’ words and melodies and Vina’s voice, they blaze across the rock firmament as VTO (“Vertical Take Offâ€), their lives mirroring the rise and fall of many sacred monsters of rock the last half century.

“We change what we remember, then it changes us, and so on, until we both fade together, our memories and ourselves. Something like that.†This is Salman Rushdie on the way our lives intertwine with the history of rock ‘n’ roll. The Ground Beneath Her Feet (1999 ) is a novel about Ormus and Vina, Indians raised in Bombay, who become the first couple of international rock. Propelled by Ormus’ words and melodies and Vina’s voice, they blaze across the rock firmament as VTO (“Vertical Take Offâ€), their lives mirroring the rise and fall of many sacred monsters of rock the last half century. I thought about Rushdie’s novel watching the documentary film Love Story, about the legendary L.A. band

I thought about Rushdie’s novel watching the documentary film Love Story, about the legendary L.A. band  “I’m a stranger here myself.â€

“I’m a stranger here myself.†