Starting with A Mask for Janus, which W.H. Auden picked for the Yale Series of Younger Poets in 1952, W. S. Merwin’s first poems were written in a traditional mode, many on themes drawn from classical mythology. In the 1960s, Merwin opened up his forms, abandoned formal lines and punctuation, and infused his poems with anti-war and environmental themes. The Moving Target (1963) and The Lice (1967) revolutionized poetry in a manner different from the way the Beats did. Merwin’s poems still hit me in the gut. A mystical, searching quality sparked by everyday perception and simple language. “Looking for Mushrooms at Sunrise” finds the poet recognizing gold chanterelles pushing through sleep and wondering “Where else am I walking even now / Looking for me”. He discovers that his “eyes are waiting for me / in the dusk / they are still closed / they have been waiting a long time/ and I am feeling my way toward them.” That from “Words From a Totem Animal,” Merwin’s characteristic evocation of the spirit haunting man’s relations with the natural world.

Starting with A Mask for Janus, which W.H. Auden picked for the Yale Series of Younger Poets in 1952, W. S. Merwin’s first poems were written in a traditional mode, many on themes drawn from classical mythology. In the 1960s, Merwin opened up his forms, abandoned formal lines and punctuation, and infused his poems with anti-war and environmental themes. The Moving Target (1963) and The Lice (1967) revolutionized poetry in a manner different from the way the Beats did. Merwin’s poems still hit me in the gut. A mystical, searching quality sparked by everyday perception and simple language. “Looking for Mushrooms at Sunrise” finds the poet recognizing gold chanterelles pushing through sleep and wondering “Where else am I walking even now / Looking for me”. He discovers that his “eyes are waiting for me / in the dusk / they are still closed / they have been waiting a long time/ and I am feeling my way toward them.” That from “Words From a Totem Animal,” Merwin’s characteristic evocation of the spirit haunting man’s relations with the natural world.

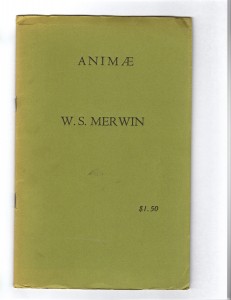

So when Kayak press published Animae, a 1200 copy chapbook, in 1969, I was ready for Merwin’s next leap into the unknown. I ordered it through a college bookstore, and when it arrived I loved immediately the paper bag feel of the green cover, the faded salmon pages. It was a shock–but not that much of a shock–to find the pages blank through the whole book. “Animae,” I thought, spirit manifest by its absence. A neat trick, and a low-budget effect, too, at $1.50, and whatever change for postage. I’ve returned to it over the years, as much probably as to any book I own with words. It is seldom listed among Merwin’s published books, and I’d never read about it until last year an academic article referenced it as containing poems about animals, as well as illustrations by Lynn Schroeder. Shocked again! Somehow, my copy ended up a misprint, or non-print. Now, of course, I see the words that are not there. I lived nearly forty years with my blank book and wish I could have it back.

So when Kayak press published Animae, a 1200 copy chapbook, in 1969, I was ready for Merwin’s next leap into the unknown. I ordered it through a college bookstore, and when it arrived I loved immediately the paper bag feel of the green cover, the faded salmon pages. It was a shock–but not that much of a shock–to find the pages blank through the whole book. “Animae,” I thought, spirit manifest by its absence. A neat trick, and a low-budget effect, too, at $1.50, and whatever change for postage. I’ve returned to it over the years, as much probably as to any book I own with words. It is seldom listed among Merwin’s published books, and I’d never read about it until last year an academic article referenced it as containing poems about animals, as well as illustrations by Lynn Schroeder. Shocked again! Somehow, my copy ended up a misprint, or non-print. Now, of course, I see the words that are not there. I lived nearly forty years with my blank book and wish I could have it back.

And yet absence is a presence in many of the poems. The easiest thing to say about Merwin’s poems is that they are about what is unexpressed or inexpressible. That is the truth, but also inadequate because we always want to find other words for the meaning we find in a poem, note how it echoes singular or universal experience, or correlate it to the uncanny in our own life.

And yet absence is a presence in many of the poems. The easiest thing to say about Merwin’s poems is that they are about what is unexpressed or inexpressible. That is the truth, but also inadequate because we always want to find other words for the meaning we find in a poem, note how it echoes singular or universal experience, or correlate it to the uncanny in our own life.

Of the dozens of books and hundreds of poems Merwin has published the last 60 years, the title of the 1973 volume, Writings to an Unfinished Accompaniment, captures what to me is the characteristic strangeness in his poems, a spiritual dimension that is part animism—a haunting “otherness†evoked in the natural world—and part personal, spontaneous, provisional instant-of-creation experience.

First to last, there’s no other poet who shivers my timbers in the way, say, “Habits†does, here from that 1973 book:

Even in the middle of the night

they go on handing me around

but it’s dark and they drop more of me

and for longerthen they hang onto my memory

thinking it’s theirseven when I’m asleep they take

one or two of my eyes for their sockets

and they look around believing

that the place is homewhen I wake and can feel the black lungs

flying deeper into the century

carrying me

even then they borrow

most of my tongues to tell me

that they’re me and they lend me most of my ears to hear them

And then there’s this little bit of scatter-shot, perfectly emblematic of the Scatter view of life:

Little children you will all go

but the one you are hiding

will fly

(“Song of Man Chipping an Arrowheadâ€)

Merwin’s poems flip me into another way of thinking about things. Sure, in the hundreds of poems there are some that fall flat and some with repetition that is merely repetition, not an altered echo. But Merwin’s latest book, The Shadow of Sirius, shows him still vigorous, clear and cool, as in “A Codexâ€:

It was a late book given up for lost

again and again with its sentencesbare at last and phrases that seemed transparent

revealing what had been there the whole way

Merwin read from his new book last Thursday at Newmark Theater. The way he reads poems, too, echoes his own astonishment at what he’s found erupting from the unconscious, a shadow hailed from afar, across a wide valley, in the dark or early morning coming-to-light.