One of our favorite Portland writers, Fred Leeson, has a sweet cover story in the inPortland section of today’s Oregonian on Sweet Baby James Benton, the smooth-singing jazz guy who is one of the last links to the great old days of the city’s North Williams Avenue jazz scene.

That scene was pretty much wiped out, along with the thriving black neighborhood that nourished it, by the midcentury sweep of urban renewal that also obliterated the bustling working and ethnic neighborhoods of south downtown, which at least led to the terrific Lawrence Halprin fountains that will be celebrated this weekend.

But enough of the heavy stuff. What we’re thinking about now is cool nicknames (Benton was being called Sweet Baby James at least a decade before James Taylor wrote that unavoidable song).

Jazz and blues and pop music have ’em. Count Basie. Duke Ellington. King Oliver. (Do we detect a pattern here?) Big Mama Thornton. Wild Bill Haley. Doctor John.

Football has ’em. Crazy Legs Hirsch. Whizzer White (who whizzed all the way to the United States Supreme Court bench). Night Train Lane (who gets honorary musical billing, too: He was married to the great Dinah Washington).

Baseball has ’em. Three Finger Brown. Big Poison Waner. Little Poison Waner. Stan the Man Musial. Moose Skowron. Catfish Hunter. Blue Moon Odom. Nuke Laloosh. (We don’t count sportswriter inventions such as the execrable “Splendid Splinter” for Ted Williams, or even “The Bambino” for George Herman Ruth: “Babe” was quite enough.)

Baseball has ’em. Three Finger Brown. Big Poison Waner. Little Poison Waner. Stan the Man Musial. Moose Skowron. Catfish Hunter. Blue Moon Odom. Nuke Laloosh. (We don’t count sportswriter inventions such as the execrable “Splendid Splinter” for Ted Williams, or even “The Bambino” for George Herman Ruth: “Babe” was quite enough.)

We confess to a longstanding if not deeply felt regret for our own un-nicknamedness. A few people in our youth called us Hopalong: Although it’s true we once created a whole Hopalong Cassidy comic book with a fresh storyline by carefully cutting apart several old Hoppy comics and rearranging the panels in a way that fit our desires, the monicker was tied more directly to our unorthodox running style, which included a couple of hops and a jump. And a few people, knowing both our middle name and our family roots in the rural South, refer to us as “Bobby Wayne.” But those aren’t real nicknames. They don’t stick.

So, the big question: How about you? Got a favorite nickname for a public or semi-public figure? (Arianna Huffington, it seems, has annointed Sarah Palin with “The Trojan Moose,” but we have a feeling the honoree should actually be willing to accept the honor.) Something you were tagged as a kid that has sadly (or not so sadly) drifted away? A name you’d really like to be known by, if only someone else would get the ball rolling? Hit that comment button. All of Art Scatter really, really wants to know.

************************************

THE CHANGING OF THE GUARDS:

Big news at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which some of us consider one of the coolest spots on Earth. Thomas P. Campbell, a late horse in the running, has been selected to replace the venerable Philippe de Montebello as director and chief executive. Campbell is 46 and widely respected by those who know him; his specialty is European tapestries. Montebello is 72 and has run the Met, extremely well, for 31 years; he retires next year. With Campbell, the Met went in-house and chose someone with impeccable professional credentials — no sure thing in the go-go museum world, where directors, like college presidents, are often chosen more for their ability to haul in the bucks than for their artistic or academic chops. Of course, Campbell’s going to have to raise tons of money, too. Good luck! Carol Vogel has the story in the New York Times. Plus, a compelling analysis from the Wall Street Journal.

Meanwhile, Alexei Ratmansky, artistic director of the Bolshoi Ballet, is leaving Moscow for New York to become artist in residence at American Ballet Theater: The internationalization of the ballet world continues apace. Again, The Times has the report.

And up the freeway in Seattle, Gerard Schwarz has announced he’ll retire as music director of the Seattle Symphony in 2011. He’s 61 now and will have been at the helm in Seattle for 26 years , guiding the orchestra, among other achievements, into its splendid home at Benaroya Hall. His leavetaking will not exactly be met with wailing and gnashing of teeth by a number of orchestra members, who have chafed under his autocratic leadership. But others at the symphony are stout defenders, and he’s put this orchestra on the map. A lot of potential replacements are going to consider this a plum job. Reports from the Seattle Times and the New York Times.

Starting with A Mask for Janus, which W.H. Auden picked for the Yale Series of Younger Poets in 1952, W. S. Merwin’s first poems were written in a traditional mode, many on themes drawn from classical mythology. In the 1960s, Merwin opened up his forms, abandoned formal lines and punctuation, and infused his poems with anti-war and environmental themes. The Moving Target (1963) and The Lice (1967) revolutionized poetry in a manner different from the way the Beats did. Merwin’s poems still hit me in the gut. A mystical, searching quality sparked by everyday perception and simple language. “Looking for Mushrooms at Sunrise” finds the poet recognizing gold chanterelles pushing through sleep and wondering “Where else am I walking even now / Looking for me”. He discovers that his “eyes are waiting for me / in the dusk / they are still closed / they have been waiting a long time/ and I am feeling my way toward them.” That from “Words From a Totem Animal,” Merwin’s characteristic evocation of the spirit haunting man’s relations with the natural world.

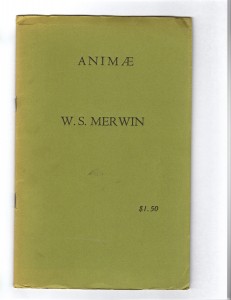

Starting with A Mask for Janus, which W.H. Auden picked for the Yale Series of Younger Poets in 1952, W. S. Merwin’s first poems were written in a traditional mode, many on themes drawn from classical mythology. In the 1960s, Merwin opened up his forms, abandoned formal lines and punctuation, and infused his poems with anti-war and environmental themes. The Moving Target (1963) and The Lice (1967) revolutionized poetry in a manner different from the way the Beats did. Merwin’s poems still hit me in the gut. A mystical, searching quality sparked by everyday perception and simple language. “Looking for Mushrooms at Sunrise” finds the poet recognizing gold chanterelles pushing through sleep and wondering “Where else am I walking even now / Looking for me”. He discovers that his “eyes are waiting for me / in the dusk / they are still closed / they have been waiting a long time/ and I am feeling my way toward them.” That from “Words From a Totem Animal,” Merwin’s characteristic evocation of the spirit haunting man’s relations with the natural world. So when Kayak press published Animae, a 1200 copy chapbook, in 1969, I was ready for Merwin’s next leap into the unknown. I ordered it through a college bookstore, and when it arrived I loved immediately the paper bag feel of the green cover, the faded salmon pages. It was a shock–but not that much of a shock–to find the pages blank through the whole book. “Animae,” I thought, spirit manifest by its absence. A neat trick, and a low-budget effect, too, at $1.50, and whatever change for postage. I’ve returned to it over the years, as much probably as to any book I own with words. It is seldom listed among Merwin’s published books, and I’d never read about it until last year an academic article referenced it as containing poems about animals, as well as illustrations by Lynn Schroeder. Shocked again! Somehow, my copy ended up a misprint, or non-print. Now, of course, I see the words that are not there. I lived nearly forty years with my blank book and wish I could have it back.

So when Kayak press published Animae, a 1200 copy chapbook, in 1969, I was ready for Merwin’s next leap into the unknown. I ordered it through a college bookstore, and when it arrived I loved immediately the paper bag feel of the green cover, the faded salmon pages. It was a shock–but not that much of a shock–to find the pages blank through the whole book. “Animae,” I thought, spirit manifest by its absence. A neat trick, and a low-budget effect, too, at $1.50, and whatever change for postage. I’ve returned to it over the years, as much probably as to any book I own with words. It is seldom listed among Merwin’s published books, and I’d never read about it until last year an academic article referenced it as containing poems about animals, as well as illustrations by Lynn Schroeder. Shocked again! Somehow, my copy ended up a misprint, or non-print. Now, of course, I see the words that are not there. I lived nearly forty years with my blank book and wish I could have it back.