On Friday night, the Portland experimental music group Fear No Music performed a selection of short pieces that went with a selection of short films and video. We were there.

On Friday night, the Portland experimental music group Fear No Music performed a selection of short pieces that went with a selection of short films and video. We were there.

Even for those of us without much technical training (which would include this department of Art Scatter), a literature of sorts exists to talk about music in non-technical terms. Histories, biographies, reviews, learned opinion expressed in lay terms, received opinion that belittles as it’s grudgingly given, even sharp new opinion that cuts things open from new angles — an apparatus of sorts exists if you want to access it.

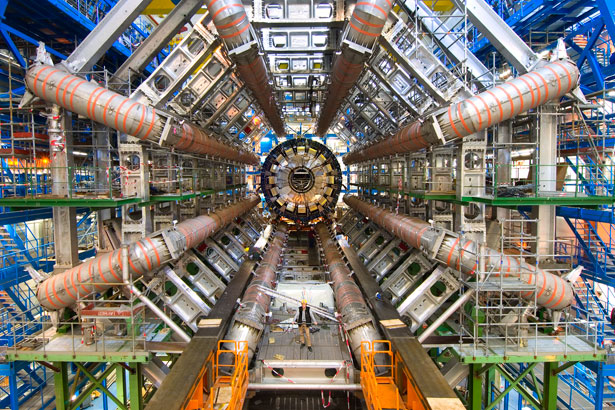

All of this involves sentences. You know, the atom of writing. But sometimes the music itself is sub-atomic. In fact, one of the threads of the past century — our immediate history, musical or otherwise — involves something we could call the sub-atomic. And sometimes our sentences don’t seem up to the chore of describing these minute and evanescent phenomena, especially a series of them.

So, right, we are preparing to use our sentences to talk about Fear No Music’s latest combine — recently created experimental visuals (video/film/etc.) and some musical experiments of the past century (and most of them on the more recent end of the time-line, though a Webern string quartet on the program was composed exactly 100 years ago). The program was called “Parallaxis: music and moving pictures,” and it was assembled (or curated) by Fear No Music and Leo and Anna Daedalus of Helsinqi media studio.

The composers chosen included some well-known modernists — in addition to Webern, there were Gyorgy Ligeti, Gyorgy Kurtag, Morton Feldman and Webern. And then there were several composers working in a similar vein, such as Karim al-Zand, Matthew Burtner, Robert Parris, Iannis Xenakis and Benedict Mason — 14 in all. Steve Ricks himself was on hand to direct his Mild Violence (2005) and Mary Wright was in the audience for her sweet, short Buttercup in Space, which was a relief after the intense percussion work of Xenakis’s Rebonds B (1989), which Joel Bluestone played with skill and intensity.

None of the names of the filmmakers (this isn’t precise — most used video) meant anything to me, but then I barely know this world at all. Although some recognizable fragments of “reality” entered into many of them, they were abstract in the various ways art works can be abstract — abstract and meditative, abstract and jangly, abstract and colorful, abstract and stark, etc.

Back to sentences and their discontents, because you’re already beginning to sense my difficulty here. Fourteen pieces of music, most of them built on small fragments of aural flotsam, sub-atomic bits and pieces, just to reiterate my original metaphor. Fourteen short films, similarly fragmentary and disjointed.

They start to flow together. We hear scraping. Scratching. Squeaking. Odd suggestions of odd chords. It’s harsh. It’s fragile. (And I’m tempted to put quotation marks around every single adjective I’ve used here!) And we see tree branches, buttons being attached, beaches, lunar scapes, lots of water images, reflections on pavement, road kill, candles, rockets and bunnies wearing weird headgear, caterpillars, a little narrative of family strife (in the 1950s?), trains, wet hair and the braiding of hair, flowers, the Broadway Bridge (!) and other local landmarks as seen during a snow storm, clouds, words, and then varieties of images that are “made up” — flashing diamonds, lozenges and other geometric figures, color fields, blotches, you get the idea maybe.

My notes on all of this are cryptic. They are not sentences. Much of the time they aren’t even fragments. And now, as I go back to them, I wonder what exactly occasioned some of the words. “Needle goes with harsh music,” for example. The needle went with the button-sewing video by Samuel Miller to Ligeti’s String Quartet No. 2 (1968), but now the particulars of that “harsh” music has been swept out of my memory. And even if I remembered, I would be hard pressed to describe it for you. I’m afraid it would involve lots of adjectives I’d want to place quotation marks around. And frankly, button sewing doesn’t begin to explain the images in their particularity, either. There was more than one button, for example, and they were various sizes. The thread-pulling was quicker than I thought it would be in one tiny sequence.

So, what am I saying here, you may well ask. That language isn’t up to the task at hand? That it either “lies” by failing to record everything or catalogs in boring detail? And even the boring detail can’t catch the movement? That the observer is unequal to the “flow” — never can be, never will be? That any task quickly becomes an essay on how limited we are, how remarkable and yet how limited? Not really. Aren’t these our basic assumptions?

Assembly required. But don’t call us if you can’t find the instructions: We didn’t pack any. Something makes me want to write you one long, smooth sentence that gets to the heart of “Parallaxis.” That collages the fragments, visual and aural, into a simple “picture” — a tree with apples and a swing hanging from one of the lower branches. Because I know that if I get into the thickets of that incredible Webern quartet, with images by Konrad Steiner (the train, European street scenes, etc.), I’m quickly left speechless. A sentence from my notes: “It’s a cool piece of music.” Which is true, but doesn’t begin to get at its fits and starts, the scraping and grinding, the sudden assertions followed by the most tentative vibrations, all in a sequence I don’t get understand at all on this first hearing.

It also doesn’t get how beautiful Steiner’s film is, or how transporting they are together — to Mitteleuropa, madly industrializing five years before World War I, everyone worrying about the loss of… what? One heart beating? If Webern’s quartet were a psychograph, somehow, we’d be worried about the nerves of the subject, sure, but we’d be even more fearful about the monster that was causing those nerves to act up in this way. Something is really wrong. Alex Ross in The Rest Is Noise ascribes it to the death of Webern’s mother (actually Ross is talking about Webern’s Six Pieces, Opus 6, but a similar melancholy is at work, just more in miniature), but we don’t really know that do we? A whole range of issues formal, psychological, sociological and political could be in there, too. Maybe we take what we need.

These days, one of the ways I’m thinking about art: It’s a description of reality, the exterior life outside the artist’s head or the interior inside the noggin or even more likely a little of both. And for me, either that description is useful in some way or not. (Careful Art Scatter archivists will know that I’m doing my usual deformations of John Dewey here.) The more useful, the more important I think the art is, at least in that moment. So, of course, in our own nervous times, I find this Webern useful. (The Austrian Webern eventually embraced Hitler during World War II even thought the Nazis condemned his work — so Webern isn’t without his problems. He was accidentally killed by an American soldier after the war.)

I also dived into the honking of Michael Lowenstern’s solo for bass clarinet, King Friday, which followed the Webern in the Fear No Music program and was played by Philip Everall with the necessary abandon. And Dutch filmmaker’s Koen Dijkman and his snowy Portland travelogue somehow amplified the rhythmic jazzy bleating of the music: My city described by Dijkman and my emotional need to blat and blather described by Lowenstern. I didn’t know I needed it until I saw it and heard it.

I find the literature interesting. Alex Ross explains the development of Webern’s atonality in a way that I think I understand, and how Ligeti and Kurtag extended it, for example. What if you’d never heard atonal music before, though? Neither Ross’s nor my own word “sounds” would be enough.

One related thought I had as I listened to the concert — we should be able to hear more music like this, and not just the “big” names, either. It’s possible to find it in weird places (I like Kyle Gann’s “program” available via his website), but at some point the classical “establishment” decided it mostly wasn’t fit for our concert halls and radio stations. There have been nibbles at the edges, but really, we have to rely on groups such as Fear No Music and Third Angle for a taste here in Portland. I thought the playing in this concert, which was incredibly demanding, was inspiring — challenges thrown down and accepted, stunning moments accumulated, conventions demolished, new techniques developed. And the video was accomplished, too, not a clunker in the bunch from my seat.

I’m still looking for that smooth sentence for you. Or is it for myself? I’m sure it has something to do with those sub-atomic particles, those strange and charmed quarks and all the odd lot, and the debris field created by the collision of such massive bodies as Beethoven and Charlie Parker. Did the video help? It made the description process utterly impossible, but on a flickering image we can sometimes build imaginary cities.