Size matters. When a traveler in an antique land stumbles upon, let’s say, a sphinx towering from the sands of a desert, a part of the astonishment is the sheer scale of the thing. What impact would Richard Serra‘s Tilted Arc have had if it had been three feet long and sitting serenely on a display table at the Museum of Modern Art?

We’ve gotten used to monumental works, and some of the — what’s the best word: terror? — of the things has leeched out of our reactions. A giant typewriter eraser by Claes Oldenburg inspires other admirations (and, for a rising generation, a bit of head-scratching: what the heck’s a typewriter?), and as the Burj Khalifa pricks the sky 160 stories above Dubai, we think of our own iconic steel giants, the Empire State Building and the Chrysler Building, with warm, compact, nostalgic pleasure. Not the biggest of the big, we tell ourselves, but still the best of the big.

Bigness and pleasure struck me the other day as I entered the rotunda of the Portland Art Museum and came face to face with Jaume Plensa‘s massive 2009 sculpture In the Midst of Dreams. Make that face to face to face: Plensa’s lighted polyester piece, 35 feet long and 24 feet wide and more than 7 feet tall, consists of the large heads of three women “buried” on a bed of stones. It’s the first thing you see when you enter the museum’s new exhibit Disquieted, and I thought immediately, “This is the most fun this space has been in a long time.”

Bigness and pleasure struck me the other day as I entered the rotunda of the Portland Art Museum and came face to face with Jaume Plensa‘s massive 2009 sculpture In the Midst of Dreams. Make that face to face to face: Plensa’s lighted polyester piece, 35 feet long and 24 feet wide and more than 7 feet tall, consists of the large heads of three women “buried” on a bed of stones. It’s the first thing you see when you enter the museum’s new exhibit Disquieted, and I thought immediately, “This is the most fun this space has been in a long time.”

Fun? At an exhibition that is built around what its curator, Bruce Guenther, calls “the things that wake us up at nights. … the things that make us mutter in the streets”?

Well, yes. Those heads fit fantastically in the museum’s rotunda. And Friend of Scatter D.K. Row got it right, in his recent review for The Oregonian, when he wrote that despite its title, Disquieted is “an expression of the calming power of beauty and artistic feeling.”

In other words: the impulse of these 38 works by 28 living artists is the fraught and fractured state of contemporary society. But what the artists produce, in many cases, is like a balm. If Guenther has an eye for the fault lines in society, he also has an eye for the skilled craftsmanship that can elevate dissent into aesthetic form. That creates an interesting rub. We’re unnerved, perhaps. We’re also entertained.

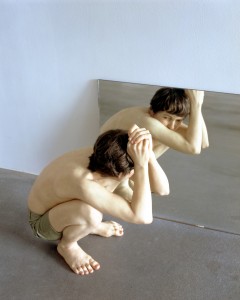

Not all of these works are big. Tanya Batura’s 10 x 17 x 10 inch sculpture Sourire en Bois, a 2007 bust of a reclining woman’s head splayed awkwardly on a flat plane, may be more genuinely disturbing than Plensa’s gargantuas, and Australian sculptor Ron Mueck’s two pieces — a tiny wall plaster of a baby looking downward like Christ on the cross; the hunkered, knotted Crouching Boy in Mirror — pack a genuinely disturbing wallop in small packages.

Not all of these works are big. Tanya Batura’s 10 x 17 x 10 inch sculpture Sourire en Bois, a 2007 bust of a reclining woman’s head splayed awkwardly on a flat plane, may be more genuinely disturbing than Plensa’s gargantuas, and Australian sculptor Ron Mueck’s two pieces — a tiny wall plaster of a baby looking downward like Christ on the cross; the hunkered, knotted Crouching Boy in Mirror — pack a genuinely disturbing wallop in small packages.

A few pieces, such as Charles Ray’s 1992 sculpture Fall ’91, an 8-foot-tall mannequin of a dominating woman in a power suit, seem already to have passed their time, although his 1990 Male Mannequin, with Brooks Brothers-perfect head and hairy genitals, still seems potent, maybe because we’re used to powerful women but still think of our privates as private: This piece could be a cooler, far less eroticized response to Courbet‘s transgressive 1866 portrait of a woman’s genitalia, The Origin of the World.

Some pieces veer toward the overtly political, without, in most cases, losing their aesthetic edge. German photographer Andreas Gursky, in two very large prints, creates entrapments of different kinds. One shows the massive cattle corrals sprawling across the plain in Greeley, Colorado: miles of animals waiting for slaughter. The other shows vast rows of workers in a textile sweat shop in Nha Trang, Vietnam. Without words, each conveys an unsettling message, and the message is double edged: (1) we treat other living beings like this; (2) the image itself is beautiful. Disquieting? You bet.

This wary tension between technique and topic — between the beauty and the beast — highlights a lot of the most intriguing pieces in the show. You can feel it in the raw energy of Glenn Ligon’s two paintings of lost battles in the African American community, Remember the Revolution #1 and In My Neighborhood #1, which use bright color and broken typographical lettering to suggest something powerful in ruins: “Remember the revolution? We lost. Motherfuckers kicked our ass in about six months. … What? Huh? What happened? Where Huey and Eldridge? …” In these paintings, engaged anger weds intense aesthetic focus.

This wary tension between technique and topic — between the beauty and the beast — highlights a lot of the most intriguing pieces in the show. You can feel it in the raw energy of Glenn Ligon’s two paintings of lost battles in the African American community, Remember the Revolution #1 and In My Neighborhood #1, which use bright color and broken typographical lettering to suggest something powerful in ruins: “Remember the revolution? We lost. Motherfuckers kicked our ass in about six months. … What? Huh? What happened? Where Huey and Eldridge? …” In these paintings, engaged anger weds intense aesthetic focus.

A couple of other black artists take a more satiric route — Ellen Gallagher with 2004’s Deluxe, her wall-sized lineup of 60 manipulated prints sending up attitudes toward hair and other matters of self-image; and Sanford Biggers’ 2008 Cheshire, a shiny lighted pair of bright red blackface lips with watermelon-seed lips.

A lot of other pieces speak to the more interior disturbances that Sigmund Freud laid to “civilization and its discontents” — the inevitable raw spots that come from the rub between the desire for independence and the fact that we are social animals. That might be the key to this place called Disquieted.

Maybe none manages it as elegantly and painstakingly as video artist Bill Viola with his 2000 piece The Quintet of the Astonished, a feverishly slow-moving portrait of five figures moving from still life to gestures of agony or ecstasy. The process takes several minutes, and is both brutal and gorgeous: Think Kathe Kollwitz and George Segal putting on a Samuel Beckett play.

Now, that’s disquieting.

PICTURED, from top:

Jaume Plensa, “In the Midst of Dreams,” 2009. Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Lelong, New York

Daniel Richter, “royit on sunsetstrip,” 2008, oil on canvas, 88 x 67 x 1 inches. The Eugene Sadovoy Collection.

Ron Mueck, “Crouching Boy in Mirror,” 1999/2002. The Broad Art Foundation, Santa Monica.

Su-en Wong, “Baby Pink Painting with Three Girls,” 2000. Acrylic and colored pencil on linen; 108 x 76 inches. Portland Art Museum, gift of the artist.