OK, this one’s a little long, but it tries to get at some important issues of how we organize ourselves, operate in the world, through the lens of two “artist managers,” Seattle’s Anne Focke and the late Joel Weinstein.

OK, this one’s a little long, but it tries to get at some important issues of how we organize ourselves, operate in the world, through the lens of two “artist managers,” Seattle’s Anne Focke and the late Joel Weinstein.

I was rummaging around the Matthew Stadler-edited The Back Room: An Anthology, and after I’d found what I was looking for (and it really wasn’t), I flipped to Anne Focke’s essay “A Pragmatic Response to Real Circumstances”. Which turned out to be what I should have been looking for all along — the tao of managing an arts organization artfully.

A little background. The Back Room started as an offshoot of Ripe, the food/culture hybrid restaurant “empire” started by Michael Hebb and Naomi Pomeroy. We won’t go into its complicated history here or its swift and unappetizing demise. The most recent Back Room, event was in October (’08), but the book was collected from writing commissioned between 2005 and 2007. Back Room events were a hybrid themselves — food, writing, music and art — threaded together by discussion.

Folke appeared at the Back Room in 2005, when she was executive director of Grantmakers in the Arts. She is best known in Seattle for her role in starting the legendary and/or arts organization in the mid-’70s. I started to write gallery, because exhibiting art was part of the mission, but early on, and/or split into a number of self-contained units, some of which still exist today. (I remember some of those early days at and/or, though I don’t think I ever met Focke — I was the publisher and dance writer for a little alternative weekly, the Seattle Sun, in the late ’70s.)

Focke’s essay is basically a memoir, beginning with and/or and continuing to the present. It focuses on Focke’s approach to creating, managing and escaping various arts projects and organizations. And it’s almost impossible to read without disappearing into some reveries of your own, comparing her experience with what you’ve seen in the world or even done yourself.

As she tracks the evolution of her management practices (and that sounds so suit-and-tie MBA and she is not), it’s surprising — at least it was to me — how early she developed her governing ideas and how consistently she kept to them. At the heart of it all is her own awareness of herself and what she’s try to achieve and then of the people she’s working with, who are inherently connected to her practice. But it all starts with that intense awareness, the awareness of the artist applied to the problems of the organization.

This seems exactly counter to the hard-headed business approach that arts boards of directors so often want to bring to their organizations. Artists running things as art projects? That sounds frivolous; leave the bean counting to bean counters, marketing to marketing experts, management to the tough-minded. But here I’ll quote John Dewey, because as her title, “A Pragmatic Response to Real Circumstances”, suggests Focke’s approach really is pragmatic in the historical/philosophical sense of the word.

Here’s Dewey very early in Art as Experience, the clearest formulation of his aesthetic ideas: “This task is to restore continuity between the refined and intensified forms of experience that are works of art and the everyday events, doings, and sufferings that are universally recognized to constitute experience.”

And now here’s Focke quoting herself in 1976, a couple of years into the and/or experiment:

“I’m often involved in finding a very tricky, delicate balance between giving enough structure, stability/credibility to assure a continued existence, and giving enough openness, flexibility, free-ness to allow for real growth, surprise, significant work and change.”

Two years later, Focke was worrying about how the growing institutionalization of her organization (and other early Boomer projects) was likely to curb their appetite for risk and change. And by 1984, she’d decided to close down and/or and let its component parts at that point go their own way, including the artists granting organization, Artist Trust, still a major part of cultural life in Washington today. Then, she wrote her board of directors (again quoting from her essay):

* and/or ws not built to last, profoundly not

* Its energy went to doing, not to building a lasting structure

* In the end, it seeded, divided, dissolved its center

* It was allowed to become a “myth,” to have a beginning and an end

I am still a little in awe at the courage of this, though in my mind I understand her thinking — sometimes it’s time for things to end. And as the essay progresses, Focke describes times when she sees that her participation should come to an end. It sounds scary and risky. Which is exactly what artists, real artists, do — face the fear, take the risk.

She then spent 15 years as a freelancer, doing a variety of things, and she admits that some of the projects that worked out weren’t her best ideas, and some of her best ideas never worked out. But when her ideas connect to similar ones of other people, then she accomplished some substantial things — such as Arts Wire, an artists news service, for example — some temporary, some that lasted.

“I usually didn’t set out to do something temporary, any more than I set out to make something permanent. I don’t start that way; instead, my action is a pragmatic response to real circumstances, one that is by nature one of a kind. Each has a cycle, a begining and an end. Some stay, some go.”

Then she becomes the executive director of Grantsmakers in the Arts, and she gets to apply her ideas about organizations to it. I’m tempted to quote the entire memo about structure/patterns/approaches that she wrote her board, but here is one of the key, suggestive, points:

“It (her proposed idea of GIA) moves lightly. It can change and will change. It avoids codifying or homogenizing its programs. It observes a few rules of thumb from James C. Scott in Seeing Like a State: take small steps, favor reversibility, plan on surprises and on human inventiveness.”

One more quote, this time about her on the ground working practice, which connects intimately to her philosophy of the open-ended organization.

“I often help move a group along by listening carefully, learning from what I hear, identifying individuals who articulate some key idea well, and then emphasizing their words or helping them take a position as spokesperson. This is not neutral on my part. Maybe it’s a kind of editing…”

Yes, but the best kind of editing — I’ll call it “artistic editing.” It is both aesthetic and practical, it responds to the environment and to the individuals within it, it finds its energy in the degree of difficulty of the problems faces, it counts on creativity, it responds to failure with more creativity. Again, like an artist. Once more to Philosopher Dewey:

“The enemies of the aesthetic are neither the practical nor the intellectual. They are the humdrum; slackness of loose ends, submission to convention in practice and intellectual procedure. Rigid abstinence, coerced submission, tightness on one side and dissipation, incoherence and aimless indulgence on the other, are deviations in opposite directions from the unity of an experience.”

Dewey was all about the “unity of an experience,” the moment when all of the difficult-to-manage forces are balanced perfectly. The aesthetic experience, in short. We tend to go to our artists for “decoration” in our lives, or maybe for “inspiration.” What I’ve come to believe, with Focke, is that artists have lots to teach us about far more practical matters, everyday matters, how to negotiate the conflicts around us in the savviest way, like a slalom skier — Dewey would suggest she is an artist of a sort, too.

Focke says that for many years she was unsure what to put on her business cards. I’d suggest “organization artist.” And this essay is a good stab at teaching us how to draw.

I now want to jump the track a second to relate part of this to the late editor/critic/bon vivant Joel Weinstein, who was celebrated by the Oregon Cultural Heritage Commission last week. That event was by turns difficult (most of those gathered knew Joel and missed him) and joyful (Joel always had a good time, it seemed). For me, already with Focke’s essay in my mind, it was instructive. Joel in his “Famous Publisher of Mississippi Mud” mode was an artist editor, too. He drummed up energy, encouraged connections among writers and artists, looked for “spokespersons” to speak up.

He also encouraged and supported risk. He really wanted you (me or anyone else) to get out there farther than we dared. Maybe he just enjoyed the fear in our eyes or the challenge of getting us to inch a little closer to the edge. But once his writers and artists got there, somewhere new, he was excited and gave them the best possible reward — he published their work.

One of the people who spoke at the event said that sometimes it felt as though you were part of Joel’s art work at least as much as you were making your own. Focke responded to that very thing in her essay, suggesting that it was a problem to be overcome, and in terms of the long-term health of an arts organization, I think that’s right — you want to confer the power of the artist to the people you work with, too. But somehow, Joel the artist got away with it, through force of personality or generosity or by virtue of throwing good parties. And Focke suggests there’s more than one way to get things done.

So, here’s to Joel Weinstein, management guru, one more time.

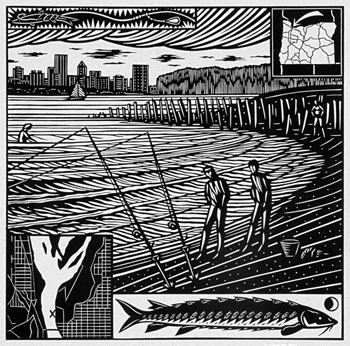

NOTE: The image is by a Mississippi Mud artist, Dennis Cunningham, called Willamette White Sturgeon, part of Portland’s Visual Chronicle.