My paternal grandmother’s name was Lizzie Lou Willingham. Not Elizabeth Louise. Lizzie Lou.

Lizzie Lou married Virgil Homer Hicks, a man whose naming signaled a certain familial aspiration. One of their offspring, my father, is named Irby Hicks. No middle name, and a first name that was a family surname. (Another of their children, my father’s sister, was named Zollie.)

The Willinghams and Irbys and Hickses came from South Carolina and Georgia, places where a naming was a serious and sometimes flowery business. On Long Island and in the Hudson River Valley, where my mother’s side of the family had their roots, the names were historical and solid — Baldwin, Seaman — but without that peculiarly Southern sense that a naming is an almost mystical occasion, an assigning of an intensely personal yet communally meaningful identification for life. My mother’s maiden name is Charlotte Lucille Baldwin, and it’s lovely. But it seems somehow less thethered, less essential to her personality or her family’s historical lot in life.

The Willinghams and Irbys and Hickses came from South Carolina and Georgia, places where a naming was a serious and sometimes flowery business. On Long Island and in the Hudson River Valley, where my mother’s side of the family had their roots, the names were historical and solid — Baldwin, Seaman — but without that peculiarly Southern sense that a naming is an almost mystical occasion, an assigning of an intensely personal yet communally meaningful identification for life. My mother’s maiden name is Charlotte Lucille Baldwin, and it’s lovely. But it seems somehow less thethered, less essential to her personality or her family’s historical lot in life.

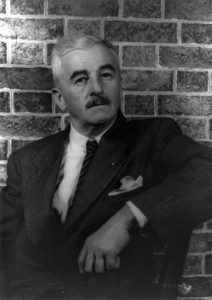

I bring this up because of Patricia Cohen’s report in the Thursday New York Times on the fresh linking of an old farm ledger to many of the names that William Faulkner used in his novels, and in 1942’s Go Down, Moses in particular. The ledger was kept in the mid-1800s by Francis Terry Leak, a Mississippi plantation owner whose great-grandson was a childhood and adult friend of Faulkner.

In it were the names of many of the plantation’s slaves, and the reading of them both angered Faulkner and excited his imagination. Cohen describes Edgar Wiggin Francisco III, the son of Faulkner’s friend, watching the great writer as he was going through the pages of the diary and “hearing Faulkner rant as he read Leak’s pro-slavery and pro-Confederacy views”:

Faulkner became very angry. He would curse the man and take notes and curse the man and take more notes.

That’s a potent vignette, and it speaks to why Faulkner still matters very much. He used many of the slave names from the journal and assigned them to white characters in his books, as he had taken a Native American name and given it to his famous fictional stomping grounds, Yoknapatawpha County. These were not, I think, so much acts of expiation or appropriation as of remembrance, and of the novelist’s determination to describe not only who “won” the battle for the South’s soul, but also the sins and brutalities that went into the waging of a confrontation in which all races and classes were engaged, and from which a great sadness fell not equally yet fully across the land. Don’t forget, Faulkner told his readers. Don’t mythologize, don’t blame others, and never forget.

That is starkly different from the attitude of another Southern writer, H.L. Mencken of Baltimore, who in his fascinating if sometimes fiercely outdated collection The American Language took many race-baiting cheap shots at the names that African American parents gave their children, citing them as examples of black Americans’ lack of education and common sense. (He seems utterly to have missed the playfulness, the sense of separate cultural identification, and the poetry in many of those names.) And that is evidence of why Mencken, once a household name, matters less and less.

Other writers have made great use of character naming, from Shakespeare’s Sir Toby Belch to Sheridan’s Mrs. Malaprop to Dickens’ Thomas Gradgrind. But Faulkner created one of my all-time favorite character names: Flem Snopes.

Flem was the anti-hero of three novels, The Hamlet, The Town, and The Mansion, that traced the rising tide of the Snopes family fortunes from horse thieves and tenant farmers to Flem’s establishment as president of the town bank and occupant of its grandest house.

Flem accomplished this by having a soul the size and consistency of something stuck in your throat: He was, in his essence, Phlegm. A cheater, a calculator, a man small and hard and avaricious. A man who married a young woman pregnant by another man because she came from a family that would be useful in his rise to the top. A man you’d like to just spit out and forget, except he sticks there, and sticks there, and sticks there, and so you can’t.

Flem Snopes. Now, there’s a name. Would a Snopes by any other name be so sour?