Sure, Franz Kafka’s Gregor Samsa is a brilliant conception, one of the touchstones of 20th century thought. But when it comes to literary cockroaches, my heart belongs to Archy. A free-verse poet, an ink-stained wretch, a nervous moralist of the demimonde, an insect in love with a slatternly cat, Archy first saw the light of print in a 1916 column by New York Sun journalist Don Marquis, who stuck by the little fellow and his feline companion, Mehitabel, through hundreds of columns and a few book collections until Marquis’ death in 1937.

If The Metamorphosis is a comic nightmare vision of the dehumanizing essence of modern culture, Archy and Mehitabel is a sadly knowing comic ode to optimism, and as such, a much more American tale. Life on Shinbone Alley, the little fetid corner of New York where Archy and his pals hang out, has a mythic quality, and the myth that comes to mind is Sisyphus: always reaching for the top, always falling back into the same old muck, always dusting off and starting the journey again. For Mehitabel the sensualist, hope is just another alley cat away. For Archy the world-wise, despair and joy are almost the same thing, and like a Beckett character but with a good deal more joie de vivre, he can’t go on, yet on he goes.

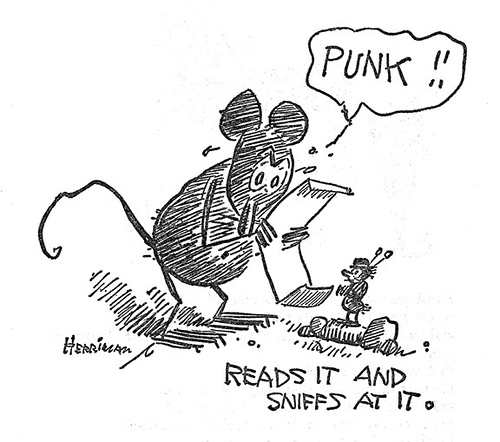

Archy, as Marquis tells the tale, just showed up one night in the Sun newsroom and, choosing Marquis’ typewriter because the columnist seemed “a little less human” to him than most humans (a race with which he held little truck), proceeded to relate the stories of Shinbone Alley. To do this required a good deal of physical pain. Archy climbed onto the keyboard and flung himself headfirst onto the keys in order to type out his first-hand reports of life on the dangerous but always fascinating streets. He wrote everything in lower-case because he couldn’t hit both a letter key and the shift key at the same time. At least he didn’t have to worry about an editor, and that alone endeared him to the corps of semi-anonymous reporters who flung their own heads against the immutable forces of the newsroom in order to record straight the tragedies and comedies and everyday occurences of the strange boisterous brute that was the big city.

What brings Archy back to mind is a visit to the Oregon Cabaret Theatre in Ashland, a spiffy space carved out of a onetime Baptist Church building just a couple of blocks away from the grounds of the Oregon Shakespeare Festival. The cabaret’s current show is a revival of Archy and Mehitabel, a lightly jazzy, hipsterish 1950s musical adaptation of Marquis’ columns. A sly fusion of the strain of sardonic optimism that flavored the United States of both the 1920s and the 1950s (decades in which a lively underworld put the lie to the official order of standardized moralism), Archy and Mehitabel provides a pleasantly raffish break from the shows at the Shakespeare festival and also fits neatly with them: After all, like the classics that the festival embraces, the enduring qualities of Marquis’ cockroach and cat are built upon a masterful scaffolding of words, words, words. (The festival and the cabaret have always enjoyed a sort of cross-fertilization of talent. In Archy and Mehitabel, stalwart festival actor Michael J. Hume is the highly effective taped voice of Don Marquis, setting the stage with brief interludes of narration.)

What brings Archy back to mind is a visit to the Oregon Cabaret Theatre in Ashland, a spiffy space carved out of a onetime Baptist Church building just a couple of blocks away from the grounds of the Oregon Shakespeare Festival. The cabaret’s current show is a revival of Archy and Mehitabel, a lightly jazzy, hipsterish 1950s musical adaptation of Marquis’ columns. A sly fusion of the strain of sardonic optimism that flavored the United States of both the 1920s and the 1950s (decades in which a lively underworld put the lie to the official order of standardized moralism), Archy and Mehitabel provides a pleasantly raffish break from the shows at the Shakespeare festival and also fits neatly with them: After all, like the classics that the festival embraces, the enduring qualities of Marquis’ cockroach and cat are built upon a masterful scaffolding of words, words, words. (The festival and the cabaret have always enjoyed a sort of cross-fertilization of talent. In Archy and Mehitabel, stalwart festival actor Michael J. Hume is the highly effective taped voice of Don Marquis, setting the stage with brief interludes of narration.)

As Mehitabel, Bryn Elizan Harris is an appealingly sensuous slouch of felineness, although you could wish for a little more oomph in her singing. Joe Massingill provides the muscle as her consorts, the bad-dude alley cat Big Bill and the oratorical theater cat Tyrone T. Tattersall; and Jessica Price and Cat Yates team as a backup chorus of assorted characters, from other alley cats to a pair of provocative ladybugs of the night. But the evening’s undisputed star is Andy Liegl as Archy: slim, hip, lithe, sad-sack, big-voiced and a natural of precise comic timing. This is a show with a backbeat, and Liegl puts the back in the beat.

As enjoyable an evening as it provides, this isn’t a perfect show. Lyrics sometimes get lost in the sound mix, some tap-dancing sequences don’t click (at least, not smoothly), the show isn’t evenly vocalized, and the jazz orchestration is taped, not live, which must add a metronomic equation to the acting. But like Don Marquis’ characters themselves, the production overcomes the odds and triumphs.

That down-but-not-out quality, intriguingly, has been a hallmark of this play, which is a little off-center for big commercial success but aesthetically too irresistible to lie down and die. It began in 1954 as a 25-minute “jazz opera” by composer George Kleinsinger and lyricist Joe Darion, which was recorded with the voices of Eddie Bracken as Archy and Carol Channing as Mehitabel. That project was expanded in 1957 into a full-blown Broadway musical called Shinbone Alley, with a book by Darion and the young Mel Brooks, and lead performances by Bracken and Eartha Kitt as Mehitabel. It ran only 49 performances, and in 1960 was trimmed back to its current chamber-musical size under the new title Archy and Mehitabel. Like Mehitabel herself, it continues to pop up sporadically, dazzling the few with wit to listen before it disappears again. Gregor Samsa may be more famous. But unlike Archy, he couldn’t write a decent lyric for the life of him.

Back beneath the stars on the outdoor Elizabethan Stage is the Oregon Shakespeare Festival’s newest production of Othello, and as always, the prime impulse is to shout, “Don’t!” Don’t elope without letting Desdemona’s dad know your intentions. Don’t listen to Iago, who’s playing everyone for the fool. Don’t give the wayward handkerchief to your husband; you should know he’s up to no good. Don’t assume your wife is guilty; talk to her and listen to her and let the truth come out. Don’t take vengeance into your own hands: You’re not God, and you’ve been duped. Othello is a great play, and great in part because it’s so frustrating: How could so many human beings be such fools? And yet, we know the capacity for foolishness is in us all.

Back beneath the stars on the outdoor Elizabethan Stage is the Oregon Shakespeare Festival’s newest production of Othello, and as always, the prime impulse is to shout, “Don’t!” Don’t elope without letting Desdemona’s dad know your intentions. Don’t listen to Iago, who’s playing everyone for the fool. Don’t give the wayward handkerchief to your husband; you should know he’s up to no good. Don’t assume your wife is guilty; talk to her and listen to her and let the truth come out. Don’t take vengeance into your own hands: You’re not God, and you’ve been duped. Othello is a great play, and great in part because it’s so frustrating: How could so many human beings be such fools? And yet, we know the capacity for foolishness is in us all.

Lisa Peterson’s production for the festival is clear, crisp and admirably straightforward, letting the mysteries speak for themselves. If Dan Donohue’s Loki-like Iago is motivated by anything beyond the pure desire to make mischief, it’s his unwarranted belief that his wife has been sleeping with Othello. As Othello, Peter Macon is fittingly charismatic, and he emphasizes the play’s hints of epilepsy, twitching and shaking as his rage and frustration grow. It’s often said that the play is more Iago’s than Othello’s, and it’s true that Iago has more lines to speak. Yet centrality is also a matter of weight and emphasis, and in those final scenes, as Othello undoes himself and disentegrates before our eyes, the play becomes his — his tale of moral usurpation, of self-destruction, of tragic self-deception. Nobody knows the trouble he thinks he’s seen. Except the audience, which winces at each misstep.

Lisa Peterson’s production for the festival is clear, crisp and admirably straightforward, letting the mysteries speak for themselves. If Dan Donohue’s Loki-like Iago is motivated by anything beyond the pure desire to make mischief, it’s his unwarranted belief that his wife has been sleeping with Othello. As Othello, Peter Macon is fittingly charismatic, and he emphasizes the play’s hints of epilepsy, twitching and shaking as his rage and frustration grow. It’s often said that the play is more Iago’s than Othello’s, and it’s true that Iago has more lines to speak. Yet centrality is also a matter of weight and emphasis, and in those final scenes, as Othello undoes himself and disentegrates before our eyes, the play becomes his — his tale of moral usurpation, of self-destruction, of tragic self-deception. Nobody knows the trouble he thinks he’s seen. Except the audience, which winces at each misstep.

Still to come: We’re on the home stretch now, with only a Friday night performance of Jeff Whitty’s The Further Adventures of Hedda Gabler and a Saturday night performance of Sudraka’s The Clay Cart to go. Stay tuned.