Today is St. Patrick’s Day, that great American bacchanal on a boisterous Irish theme, and here at Art Scatter World Headquarters we trust our stockholders are out on the streets whooping and hollering and downing tankards of green beer and generally celebrating the corning of the beef. Or not.

My own plans are slightly different. I figure instead on relaxing in my lush private retreat overlooking the grand garden estate I purchased with a small slice of this year’s Art Scatter upper-management bonus distribution — how else could we attract the best and the brightest talent in these tough times? — slowly savoring a fine Irish whiskey served by one of my several personal assistants as I contemplate the successful completion of a full year of the Artificial Me.

The funny thing is, I don’t feel in the least artificial, and I’m wondering if that makes me and Bernie Madoff blood brothers.

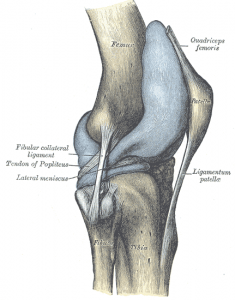

Yet here I sit, and stand, and walk, and even bend, things that had gradually become so difficult that a year ago today I found myself lying in an operating room at Providence Portland Medical Center, where a team led by the blessedly skillful orthopedic surgeon Dr. Steven Hoff scraped and jabbed and sliced into my left leg, stretching tissue wide enough to insert something very like a hockey puck into the degenerated space between my femur and tibia that had become the laughably inadequate remnant of a once solidly workable knee. (Strictly speaking this isn’t quite true. I didn’t “find myself” lying in the operating room; I never saw the place. By that point, swaddled in the sweet bassinet of modern pharmacology, I was deep into lullaby land, and thank goodness for that: This was no Civil War surgery, with hack saw and clenched teeth and a bottle of booze to stanch the pain.)

Today, after a few months of rehab under the gentle yet firm prodding of Providence’s physical therapy squadron, I’m happy to report the bailout was a success. For some time I’ve been back to “normal” — that is, under ordinary circumstances I don’t think about my knee any more than an AIG executive thinks about ethical responsibility. Sure, there’s a little tightness of the skin around the scar tissue, but that’s just the new normal: Think of it as one of those niggling oversight requirements that might go away if you just ignore it. Before surgery, stairs and even slight inclines on sidewalks were obstacles. Before surgery, I hesitated between walking-sticks and walking-canes, uncertain of which was more stylish/less obtrusive (and foolishly self-conscious in a way I hadn’t felt for years) but always with one or the other at hand. Now, sticks are long forgotten and stairs are just life.

In other words, everything’s natural — except for that highly artificial, nonorganic, composite hockey puck that separates bone from bone; that blessed chunk of shock absorber that takes the stiffness out of my ambulatory stride. I am artificially normalized — engineered into effectiveness. And while the whole process has hardly been on the order of a heart transplant — I join millions and millions of other people who’ve had knee or hip replacements — I have dipped my toes into the brave new world of Robot Man. I am, just slightly, less a biological being than when I began. And I feel good about it. I feel stimulated.

Now, I’m as green as the next fellow, and I don’t mean Irish, although I do have a drop of the blood. I believe in organic. I try to limit my car time. I recycle, I use cloth grocery bags, I eat my vegetables (and not, truth be told, much meat at all). But I’ve come to realize that when it comes to the basic physical me — this shell of flesh and bone that houses and to a great degree defines whatever the elusive quality is that makes me what I am — I contain far more additives than the food I usually eat. I’m not natural, any more than our Wall Street buccaneers are balanced in their view of a fair and equitable approach to the long-term maintenance of the engine of capitalism.

There are the blood pressure pills — three kinds, taken daily, a pharmaceutical cocktail that keeps the thumping at a rational rate. There is the daily half-dose of aspirin, an addition to the bloodstream that my general practitioner dictated several years ago with the wry explanation that “I prescribe this to all my patients your age, on general principle.” There is, of course, that hockey puck in my knee.

I’m far from alone. In fact, compared to some people I’m a piker at this game. Baseball players inject themselves with steroids and human growth hormone, looking for an edge that might erupt into a 450-foot home run or a barroom brawl. Students speed up before a test and zone out afterwards, both with the aid of pharmaceutical stimulants or depressants. People unhappy with their noses have them shaved and sculpted (Barbra Streisand, showing great good sense, refused to be turned into just another pretty face, instead retaining the uniqueness that made her famous). Too heavy? Tie off your stomach. Too flat? Buy yourself, in the famous words of A Chorus Line, some artificial tits and ass. More substantively, you can get a new heart, a new machine-crafted hand with working fingers, a reconstructed palate without the cleft. You can, in ways previously undreamed, reinvent yourself. And technologically, we’re only standing in the doorway of this brave new world. Will we really, at some point, transform ourselves into continually regenerating biological machines — into forever people? And with what implications to our psychological and social health?

All right, that’s getting ahead of ourselves. But what about these “little” steps of biological enhancement — the ones, we might argue, that began with the adoption of eye spectacles, which, following generations of experiments with magnification reaching back as far as 8th century B.C. Egypt, are supposed to have been invented in Italy by one Salvino D’Armate in the year 1284? Is it natural for the human species to enhance itself artificially? Do our brains and ambition make it inevitable that we turn ourselves, at least partially, into machines? How do we monitor the possibilities we’ve given ourselves? How do we decide when an artificiality is good and when it’s bad? We revile our athletic heroes for goosing up their bodies beyond the point of human probabilities. Yet my son, who gets skin rashes, rubs a steroid salve on his arm, and the rash goes away. Would he better off with the rash? If he were an athlete, would the use of this medication be cause for barring him from competition?

And what are the long-term implications? It’s a question asked too infrequently in our board rooms, in our shareholder meetings, in our legislatures, in our lives. Does short-term profit-taking lead to long-term loss? Will the raiding of the Oregon Cultural Trust by a cash-strapped state legislature kill the golden goose? Does the stripping of school curricula to “the basics” impoverish the futures of a generation? Will the armed invasion of a foreign nation create more enemies than it defeats?

Things have consequences, and we don’t always know what they might be. Take the hockey puck in my knee. It’s the result of a string of circumstances, and I’ll trace them quickly for you backwards in time, like Harold Pinter telling his story in reverse in “Betrayal.”

My left knee wore out because it had been doing double duty for decades, carrying the brunt of the load for a right leg that couldn’t pull its weight. Last year’s surgery followed a previous surgery in 1984 to correct a curvature in my left femur that caused me to walk with a torque that threw my leg out of line, with the result, in my surgeon-at-the-time’s elegant phrase, that it was “shearing off at the knee.” To realign it he cut a pie wedge out of the femur, straightening the leg but also shortening it by more than an inch. While rooting around he had to work around several large metal staples — there’s Robot Man at work again — inserted circa 1959 to slow the growth in the left leg so it wouldn’t end up inches longer than the right. The staples worked only on one side, causing the curvature of the femur that led to the surgery in 1984. And the staples were inserted to compensate for the effects of an unfortunate collision with a polio virus that had the bad grace to visit in 1948, four years before Jonas Salk developed the vaccine — artificial stimulant! — that would have rendered the virus harmless. Instead it chomped up the neurons up and down the right leg and left it lighter and leaner than a 401(k) account after the Great Collapse of ’08.

Other enhancements, meanwhile, took place on the right side: At one point a muscle that attached between the knee and hip was transplanted to attach between the knee and ankle, providing a little pulley action that hadn’t existed before. At times I think of my body like the Lower Columbia River, dredged and deepened for better navigation but with sometimes unanticipated side effects.

Do I regret any of those steps? Only in the fantasy world of what-if. What-if the virus and I had never met? What-if the neoconservative revolution that unleashed the economic collapse of 2008 had never occurred? We did, and it did. You deal with what you have to deal with, when you have to deal with it. And you know that whatever steps you take could be mistakes. After thinking them through, you take them, anyway. Maybe it isn’t natural, but I like being Artificial Man. I like having a knee that works. It’s way better than the alternative.

So here’s to you, St. Pat. Thanks, I guess, for running out the snakes. When I toast you with a shot of Irish whiskey I know I’ll be killing off a few more of my remaining brain cells. But it seems worth the price, although I’ll never really know. The Artificial Me salutes the Legendary You. Maybe we won’t be sending out dividends to our Art Scatter shareholders. Maybe we’re a trifle short on the green. Still, it’s been a good year.