CHARLOTTE LUCILLE BALDWIN HICKS

February 20, 1920 – October 17, 2013

This is the talk I gave at my mother’s memorial celebration on Saturday, November 9, 2013, at the First Baptist Church of Ferndale, Washington, where Mom had been a member for many years. She was born in Holtville California, near the Mexican border, and grew up in Richmond, California, across the bay from San Francisco, and moved with her young family to Ferndale, Washington, in 1952. The written talk is a little bit longer than what I delivered on Saturday; I had cut a few passages to keep the talk from getting too long. – Bob Hicks

*

When I got the phone call from my sister telling me that Mom had died, I was shocked. Oh, no: the moment’s come! It’s always a shock, of course, that moment of passing, even when you know that it might happen at any time. But only the night before, Mom had had a little crisis, and was taken to the emergency room, where she spent several hours, and after the doctors announced that her vitals were fine and she was in good shape, she went home again. So when she died in her bed a few hours later, yes: it was like a piercing of the heart, or a punch on the chin.

Mom was 93 years old, and she died in her sleep, which was a blessing, and as I was driving north later that morning from Portland to Ferndale, thinking and remembering and feeling, I remembered the last crisis Mom had had, just about a year ago, when it seemed that she might die. She was so close to it that the doctors told us to be thinking about end-of-life questions, including the big one: Should we pull the plug? Mom had long ago made sure we knew she didn’t want to be maintained artificially in a vegetative state. But knowing when that time’s arrived isn’t always easy. She was conscious enough that we talked with her, and asked her. Do you feel like you’re ready to go and see Daddy again, or do you feel like you still want to be here? Mom replied without hesitating, emphatically and with what sounded to me, at least, like surprise that there would be any question about it: “Well, I want to LIVE!”

And live she did. She revived, and lived, I think, very happily in what I’ve come to think of as her Gift Year – a gift to her, and a gift to all of us. So when she finally died, peacefully, it felt very much like the loss it is, but it also felt like a fulfillment. Death paused, and when he did come to visit, he did so kindly.

I’m speaking this afternoon for all seven of Mom’s sons and daughters, and for her grandkids and great-grandkids and nieces and nephews and friends, and for the wonderful caregivers at Highgate Senior Living in Bellingham who did so much to make her last couple of years as comfortable and loving as possible. All of you. All of us. And this is a good time to say that I’m speaking for the not-quite-born, too. Mom’s grandson Bud and his wife, Maryam, couldn’t be here today because they’re expecting a child any day now. That child will be a daughter, and her name, like Mom’s, will be Charlotte. But I can’t really speak for everyone, because for each of us Mom was someone unique, and I think that was one of her great gifts: she truly saw people individually, and made her life fit with them individually, and loved them individually. And that means we all have our own memories.

My brother John recalls, fondly, “sitting up on the counter in the kitchen in the old house on Sundays, watching Mom make dinner and telling her about what I’d learned in Sunday School and singing together as a family to the ‘Sing Along with Mitch” records.”

My brother Bill remembers Mom’s sage advice: “If you look for bad in people, you’ll always find it, because we’re all people. So look for the good.”

My sister Barb, who moved from California to be with Mom during her final couple of years, says her fondest memories are from those times. “When I was feeling frustrated, overwhelmed or anxious,” she says, “my coping mechanism was to visit Mom, because I always felt in the present moment with her. My own life fell away as we went for walks, Mom being always very observant, as I pushed her in the wheelchair, of what was happening in the natural world: the weather, flowers blooming, leaves changing color. She didn’t have much memory of what was going on in her day-to-day life, but her memory of the past, particularly of the period when she was a young girl growing up with three sisters, was still vivid.”

My sister Laurel, who like Barb spent part of most every day with Mom, says that Mom was “a well of consolation to me, a fount of intuitive wisdom.” Then she points out, just a little humorously, that Mom also had what we used to call a strong constitution: “She had seven children and lived to be 93, anyway.”

Well. Seven kids is a houseful. And it wasn’t a very big house, that little home of ours with only one real bedroom and another stuck down a concrete walkway behind the garage, and a narrow front porch that was pressed into service for sleeping. Mom and Dad slept on a fold-out couch in the living room, and things were – cozy. That was before Dad and the younger kids built a bigger house out behind, back where the old barn had been. The three older of us were gone by then, but we visited many times. Having seven kids is challenge enough. Keeping all of us in line in that little house was something else again. Mostly, Mom did it with immense patience, and warmth, and quiet diplomatic skills. We could be an obstreperous lot, and of course sometimes she’d get exasperated with one or another of us, and shout at the miscreant to cut it out. Inevitably, she’d start at the top of the list, agewise, beginning with Melinda, and work her way down until she landed on the right name. But sometimes she’d go too far, and have to back up again, and when that happened, everyone would start laughing, including her, and the crisis would be averted. She was expert at averting crises. Once we were older, she used those skills for many years as a teaching assistant in special-education classes in the public schools, and even served a term as president of the local teachers’ union.

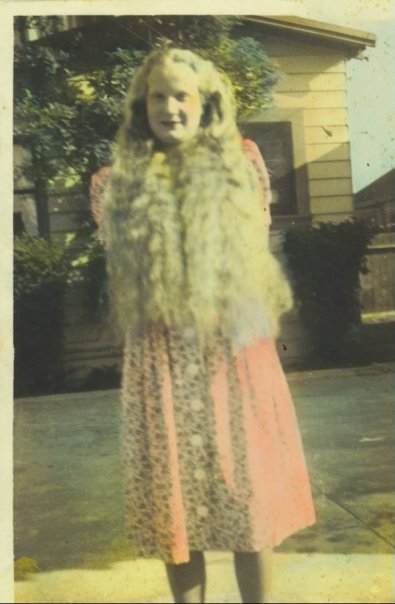

I remember how very pretty Mom was. I knew that, even as a very young boy. She was very striking, like a Nordic beauty, though we aren’t Scandinavian. We have a picture of her, as a teenager, with her hair flowing halfway to Australia, improbably long, and seeing the photo would make her shudder just a bit. She hated wearing her hair that long; it gave her headaches. But her mother didn’t want her to cut it. Finally she stood up for herself: snip, snip, snip. Mom was pretty, and gracious, and she worked hard, and as you can imagine she was tired a lot, but she was also joyful. As she swept or cooked or ironed laundry – which there was aplenty of – she would sing, in a lovely warm soprano, songs that came to her mind. They might be hymns or spirituals, and more often, I think, popular songs: “Summertime,” “Lazybones,” “Mockingbird Hill,” “Begin the Beguine.” I especially remember her singing, happily, “Oh, What a Beautiful Morning,” a song that seemed to encompass the way she chose to look on life. Music was everywhere in her life, and therefore, also in ours. As a young woman, before we were born, she sang “Loch Lomond” on the nationally broadcast radio program The Major Bowes Amateur Hour. She played violin, and had her picture in the newspaper with her small string orchestra. At one time or another her children played, variously, the trombone, French horn, violin, cornet, tuba, string bass, ukulele, guitar, and flute, and I’m probably leaving a few things out.

We didn’t have a lot, but Mom made it her mission to bring beauty into our lives. This took a lot of forms, from the Chopin album that might be playing as we all settled in to sleep, to the craft projects: making valentines and collages and holding them together with just-stirred-up flour paste; carving pumpkins and creating makeshift Halloween costumes; stretching taffy, which filled the house with that intoxicating vinegar smell. Mom taught me how to roll a proper pie crust, a skill I’ve unhappily lost in the years since. It was ages, I think, before I realized that pinking shears had a purpose other than cutting out paper silhouettes and doing various art projects.

She valued the few nice things she had, like the carved Chinese chest that Dad had brought home from his travels, and like a small number of good clothes. As a very young boy, before I started school, I liked to tuck myself away inside her closet, where I could surround myself in a little jungle of fabric, and dream. She had one dress hanging there that she loved, and so did I: a dress with little seahorses printed on it. Those seahorses were magical to me, and one day, in one of those moments of astonishing dumbness that strike kids, I got a pair of scissors and neatly cut one off, near the bottom. Mom was horrified, and crushed, and angry at first, and as it slowly dawned on me that this might not have been a good idea, I blurted out, “But I only took one!” Mothers make sacrifices, and this was a big one. Thank goodness I was more important to Mom than her favorite dress was. Forgiveness is a very big thing.

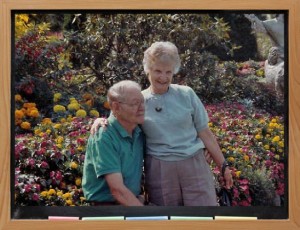

We seven kids – Melinda, Laurel, Barb, Chuck, Bill, John, and I – were very much what Mom’s life was about. She devoted herself to us, prodding us and encouraging us and telling us we could do or be anything we set our minds to. So we all went off and did things, which made her proud, and we often didn’t get home for long stretches, which made her sad. But even more than she was devoted to us, I think, she was devoted to Dad, who she married when she was 21 and he was 25, and lived with for almost 70 years, until he died in July of 2011, at age 94. In our minds they were inseparable. Charlotte and Irby, Irby and Charlotte, Mom and Dad. In her later years Mom loved to tell the story of how she walked across the Golden Gate Bridge as a high-school girl, on the day it opened in 1937, and how on that very same day Dad, whom she hadn’t yet met, steamed beneath the bridge into port as a young merchant sailor; and how, not a whole lot later, they were introduced by Dad’s sisters. It was fate, she was sure. I know Mom and Dad had to have had their differences, but my memory is that, when it came to raising us, they always showed a united front. There was no playing of one against the other, and their affection for each other is deeply embedded in our memories. Little things. They held hands. They laughed together. When they still could, they took drives through the countryside. They were a team.

Mom loved a bowl of ice cream, and she didn’t love her vegetables, even though Dad kept a big garden, and over the years she must have fixed a ton of them for the family to eat. In later years she just stopped. She told us she never could stand vegetables, but she ate ’em anyway to set a good example for us kids. Just one more in a cavalcade of noble sacrifices. There were a lot of them, and a few rewards. Mom liked a second helping on her plate, and and every now and again, a short glass of wine. “Now, Charlotte, do you really think you need that?” sister Lindy remembers our father saying on such occasions. Mom was generous and loved all pleasures, which sometimes worried Dad, who was a more cautious soul.

When I asked my sisters and brothers what stuck in their own memories, John said, “I treasure most an appreciation for beauty and learning that I think we were given by both Mom and Dad. That legacy continues.” I agree. These were invisible gifts, but essential and wonderful and enduring. I would often look through Mom’s art-history books from college that she kept all those years, sometimes flipping through the pages along with her, sometimes curling up with them on my own. In my writing life I often engage with works of art, and on the day that Mom died I had very recently happened on an 1877 painting by the French artist Henri Rousseau, called “Landscape with Bridge.” It’s a simple painting, flat and homespun. A woman in a ribboned hat approaches a walking bridge across a river, heading to the other side. In a small boat below, a ferryman waits, like Charon on the River Styx. But the woman has no need of his services. She has her bridge, and waiting on the other side, atop a hill, is a humble but beautiful church, its spiral pointing to the sky. She’s on her way.

It’s a very big thing, this going away, this transition from flesh and blood to spirit and memory. The novelist Russell Hoban wrote this contemplation, in his book “Fremder”: “More and more I find that life is a series of disappearances followed usually but not always by reappearances; you disappear from your morning self and reappear as your afternoon self; you disappear from feeling good and reappear feeling bad. And people, even face to face and clasped in each other’s arms, disappear from each other.”

And yet they don’t.

My sisters Barb and Laurel both told me something remarkable about Mom’s final evening on Earth, when she was in the emergency room. At one point, they said, she very clearly raised her arms above her head, toward the sky – in Barb’s words, as if to say, “I’m coming home!”

A few days later, Barb was in a Bellingham bookstore, doing a signing of her latest book, and something happened. She says, “One of the caregivers who had been wonderful to my Mom came in and told me that when Mom came home from the hospital late the night before she died , she was giggly and happy. When the caregivers who got her ready for bed asked why she was so happy, she said she had seen Irby at the hospital and he was coming to get her. She died in her sleep five hours later. Goosebumps! Mom and Dad shared a love beyond death.”

A little of that love stays here, too, with each of us. It’s a great, great gift. Their love washes through us gently and generously, and when the time comes, we’ll pass it along. Thanks, Mom. Goodbye.