By Bob Hicks

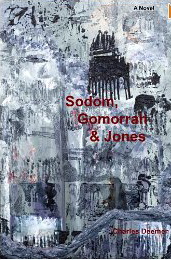

CJ Jones is 75-odd years old, and although he moves around slowly, he thinks in short sharp bursts, which in Portland writer Charles Deemer‘s new novel Sodom, Gomorrah & Jones translate into short sharp chapters.

It’s almost more of a novella, really, if the categorizing makes a difference, with a lot of air: some of those chapters aren’t much more than a paragraph long. And the writing’s lean – bent on telling the story rather than playing around with the words, although the story, such as it is, is not of the traditional narrative sort. Things meander, tautly, without an awful lot happening.

It’s almost more of a novella, really, if the categorizing makes a difference, with a lot of air: some of those chapters aren’t much more than a paragraph long. And the writing’s lean – bent on telling the story rather than playing around with the words, although the story, such as it is, is not of the traditional narrative sort. Things meander, tautly, without an awful lot happening.

But as you’re reading it you gradually begin to understand that the novel is moving on two tracks. The first tells what CJ, a retired history prof at Portland State University whose specialty had been the moral debacle of the United States’ dealings with its Indian nations, is doing and thinking. The second, more subterranean, suggests what he’s feeling. And when the thinking and feeling finally align, both CJ and the novel ride off into the sunset – CJ into a diminished but genuine if intriguingly detatched rejuvenation of further adventures, the novel to a neatly clipped conclusion.

Sodom, Gomorrah & Jones is a quick read, and deceptively simple. It begins at a funeral in Portland and ends in a minivan camper in Mississippi, with an audio reader on the stereo reciting one of the bawdier passages of Chaucer’s The Miller’s Tale. In between –through folk singing and drinking and encounters with younger women and older women and new technology and new sexuality and his belated discovery of the other great love of his late wife’s life – CJ slowly sheds the parts of his past that are weighing him down and keeps the parts that can catapult him into vigorous old age.

Deemer’s novel flips easily through flashbacks and current events, and it can hit lightly on some of its scenes, like a screenplay (and in fact, Deemer has taught screenwriting at PSU for several years). It also drops in frequently on CJ’s increasingly hopeless and cynical view of the state of the nation: he was, after all, a historian and a political activist. As offhand as these passages can seem, they’re a crucial part of the novel, both in defining its position in the culture and in reporting the core of CJ’s character. Deemer doesn’t dwell on CJ’s political positions, and his references can pass so quickly that they sometimes seem more like sound-bite position statements than explorations of complex social issues. Yet the novel’s opening sentence – Was the American Dream coming to an end? – is a serious proposition that Deemer examines, in various forms, from beginning to end.

Sometimes the discussion is bleak:

“Helen said that sometimes CJ talked like a jilted lover when he discussed the sixties. It was true. Hedonism had won out as far as CJ was concerned, the great betrayal of the sixties. The question to CJ became, Were the sixties the canary in the coal mine, warning of the fall of the American empire? Had America become the new Sodom and Gomorrah?”

Yet in its gruff and curdled way Sodom, Gomorrah & Jones is a comedy, and some of the rough-hewn humor of the sixties courses through a scene of his first Thanksgiving dinner with his new wife’s parents, when his father-in-law inexplicably asks him to say grace:

CJ had never said grace in his life. He shot a glance at Helen, across the table, who nodded.

“Of course,” said CJ.

Mrs. Stevenson smiled at him.

CJ closed his eyes, getting ready, then opened them.

“Thank you,” he began. He stopped and started over. “Dear Lord. Thank you for the bounty of food we enjoy today and for the opportunity to share it with family and loved ones. Let’s not forget the noble savages whose kindness got us through our first winter, even though we later rewarded them with a policy of genocide that …

Mr. Stevenson bolted to his feet with such effort that his chair toppled to the floor.

“That’s enough!” he said.

He was so red in the face that CJ wondered if he were having a stroke. He turned and hurried out of the dining room.

Helen was on her feet, also red but rising more carefully, and chased after her father.

CJ closed his eyes again. What had possessed him? How could he be so stupid?

When he looked up, Mrs. Stevenson was smiling at him.

“Carleton, would you carve the turkey, please? You do know how to use an electric knife, don’t you?”

I knew from following Deemer’s writer’s blog that he’d rediscovered John Dos Passos’ 1930s U.S.A. Trilogy, and as he makes clear in this post he’s borrowed some of the Trilogy’s structural elements, adapting Dos Passos’ liberal use of contemporary newspaper clippings to the background dronings of news programs on CJ’s television set. It’s a tribute to Dos Passos’ imagination and Deemer’s contrarian sensibility that the techniques still seem fresh and out of the mainstream.

Something else strikes me as important to understanding this new novel: Deemer doesn’t really care if it hits the big time. It’s published by Portland’s small Round Bend Press, in paper and e-reader versions, far from the commercial mainstream. It could have been longer, more fleshed out, and at times better edited and less repetitive. It could have paid closer attention to the current fiction market and played to the trends. That sort of ambition seems to have given way to something closer to the bone: to get it the way Deemer wants it, with hopes but no expectation of anything else. That may be limiting. But in a way, it’s the whole point of the novel, because it’s also liberating: both the novel and its hero are free to become exactly what they want to be.