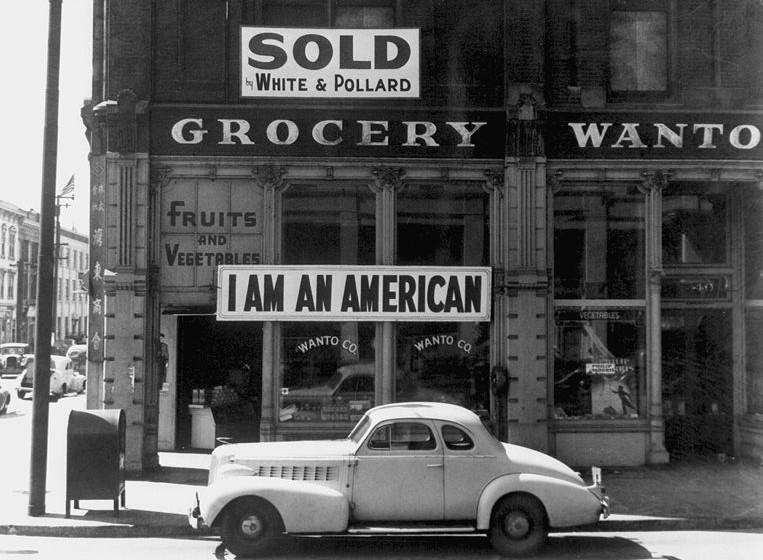

Japanese American storefront, 1942. Dorothea Lange

Japanese American storefront, 1942. Dorothea Lange

By Bob Hicks

In 1935 Sinclair Lewis published his novel It Can’t Happen Here, about the Hitler-style takeover of the United States by a power-grabbing populist president. The book’s title was satiric. Lewis meant that it very much could happen here, and if we didn’t pay attention, it just might.

On February 19, 1942, scant weeks after the Japanese aerial attack on Pearl Harbor, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, authorizing the rounding-up and “relocation” of Japanese American citizens, mostly from the Western states, into internment camps for the duration of World War II. More than 140,000 people, all of them uprooted from their ordinary lives, ended up in the camps.

On March 28, 1942, little more than a month after the roundup had been set into motion, a young Japanese American man named Minoru Yasui — he’d been born on October 19, 1916, in Hood River, and earned his law degree from the University of Oregon in 1939 — walked into a police station in Portland and dared the officers to arrest him for breaking curfew. They obliged. Yasui landed in jail and eventually in a relocation camp. Yasui wanted to test the constitutionality of the internment law, and his case finally went to the United States Supreme Court, which ruled that his arrest and incarceration were legal. Yet he kept fighting, during and after the war. He was a Good Citizen.

On March 28, 1942, little more than a month after the roundup had been set into motion, a young Japanese American man named Minoru Yasui — he’d been born on October 19, 1916, in Hood River, and earned his law degree from the University of Oregon in 1939 — walked into a police station in Portland and dared the officers to arrest him for breaking curfew. They obliged. Yasui landed in jail and eventually in a relocation camp. Yasui wanted to test the constitutionality of the internment law, and his case finally went to the United States Supreme Court, which ruled that his arrest and incarceration were legal. Yet he kept fighting, during and after the war. He was a Good Citizen.

On Monday, March 28 — 69 years to the day after Yasui’s arrest — Artists Repertory Theatre will present a staged reading of Good Citizen, Portland writer George Taylor‘s play about Yasui’s good fight. The play, which is still getting a few revisions, is a finalist for the 2011 Oregon Book Awards. It’ll be performed at 7:30 p.m. on the theater’s Morrison Stage; tickets at the door only, suggested donation $8.

Many kinds of “it” can happen and have happened here, and while Lewis’s nightmare vision of a fascist takeover always remains a possibility, Yasui’s tale suggests competing kinds of “it” — the dark, fearful, racist “it” that allowed the relocations to happen in the first place, and the determined “it” of a not-so-average man who believed in the nation’s best principles and devoted his life to undoing the wrongs committed not just against him and his fellow Japanese Americans but against the notion of American democracy itself. And here’s the thing: While it’s true the battle’s never over, Yasui won — if not in court, then in the sweep of history.

Which makes it something of a shocker that his story is so little-known.

“One of my concerns at the outset was, ‘Well, here I am a Caucasian telling this story. Is that insensitive?'” Taylor said over coffee the other day. “And then I realized that this is not just a Japanese American story. It’s about being American. The choices we make as a country.”

One problem any playwright faces in approaching a historical subject is that history is messy and a play needs to be at least comparatively neat. You can get lost in the research and complexities and offshoots — the larger picture that makes history such a fascinating and untamable beast — when your immediate task is to suggest that complexity but keep the story clear and focused and dramatic.

“Yasui was a brash young man,” Taylor said. “What was his journey going to be through the play?”

Well, there was that arrest. And the rounding-up of Oregon Japanese Americans in an old livestock center in North Portland (it’s now the Portland Metropolitan Exposition Center, better-known as the Expo Center), where close to 4,000 were herded. Then it gets on the train with them to Minidoka, the relocation camp in the dry windy nothingness of southern Idaho.

And Taylor embarked on his own journey.

“When I started this thing I thought, ‘Everybody needs to write an unproducible play, right?” he commented wryly. At one point Good Citizen had 28 named characters and a bunch of unnamed ones — “and we’ve gotten it down now to eight actors.”

“When I started this thing I thought, ‘Everybody needs to write an unproducible play, right?” he commented wryly. At one point Good Citizen had 28 named characters and a bunch of unnamed ones — “and we’ve gotten it down now to eight actors.”

Those eight, who are being directed by Philip Cuomo, stay busy. And they have some serious chops. Ako, who was sterling last season in Ping Chong‘s stage adaptation of Akira Kurosawa‘s movie classic Throne of Blood, and Daisuke Tsuji (Culture Clash’s American Night) are up from the Oregon Shakespeare Festival in Ashland. Dan Kremer, another longtime standout at OSF and other regional theaters, is down from Seattle. They join Portlanders Michael Fisher-Welsh, Jeff Gorham, Chris Harder, Eric Hull and Jennifer Lanier.

One of Taylor’s temptations was “the whole issue of economics on the West Coast at the time.” In farming communities, white farmers often saw their Japanese American neighbors as competitors, and sometimes openly coveted their land. A lot of people who spent time in the camps never did get their property back: It somehow passed along into white hands. Wikipedia reports one California agriculture leader’s comments from a 1942 article in the Saturday Evening Post:

We’re charged with wanting to get rid of the Japs for selfish reasons. We do. It’s a question of whether the white man lives on the Pacific Coast or the brown men. They came into this valley to work, and they stayed to take over. … If all the Japs were removed tomorrow, we’d never miss them in two weeks, because the white farmers can take over and produce everything the Jap grows. And we do not want them back when the war ends, either.

There’s a whole new play in that. Good Citizen gives it a nod, but sticks to its own story.

The question of military necessity, which was used to justify the internments, does come up. K.D. Ringle, a lieutenant commander in Naval intelligence, notably contradicted the need for internment. “He felt he knew who the bad apples were in the Japanese communities,” Taylor said. “He could spend a couple of months rounding them up, and there was no need to have everyone interned.”

No need. But in war-shaken America, lots of desire.

A lot of the Yasui story revolves around its legal complexities. Taylor’s spent a good deal of effort streamlining them and making them more present-tense. “Part of it’s a court case,” he said. “I was quite faithful to the language of the manuscripts; I wanted to honor that. At the same time, a lot of that language is passive. I mean, this is a play, after all. I can’t forget that.”

Taylor’s journey with this material began a couple of years ago when a friend, Karen Fink, invited him to help her direct a staged reading of the transcript to Yasui’s trial. The reading was for the Oregon Minority Lawyers Association, and the actors were 16 attorneys. Things developed from there. He kept writing and dramatizing. Good Citizen won CoHo Productions’ 2010 New by Northwest play competition. It was shortlisted for last year’s Eugene O’Neill National Playwrights Conference and the Fratti-Newman Political Play competition in New York. It snagged that Oregon Book Award nomination. And here it is again, at the next step on its long and winding road.

Next stop? Taylor laughed a little ruefullly. “I want to get the thing out of developmental hell,” he said.

It could happen here.

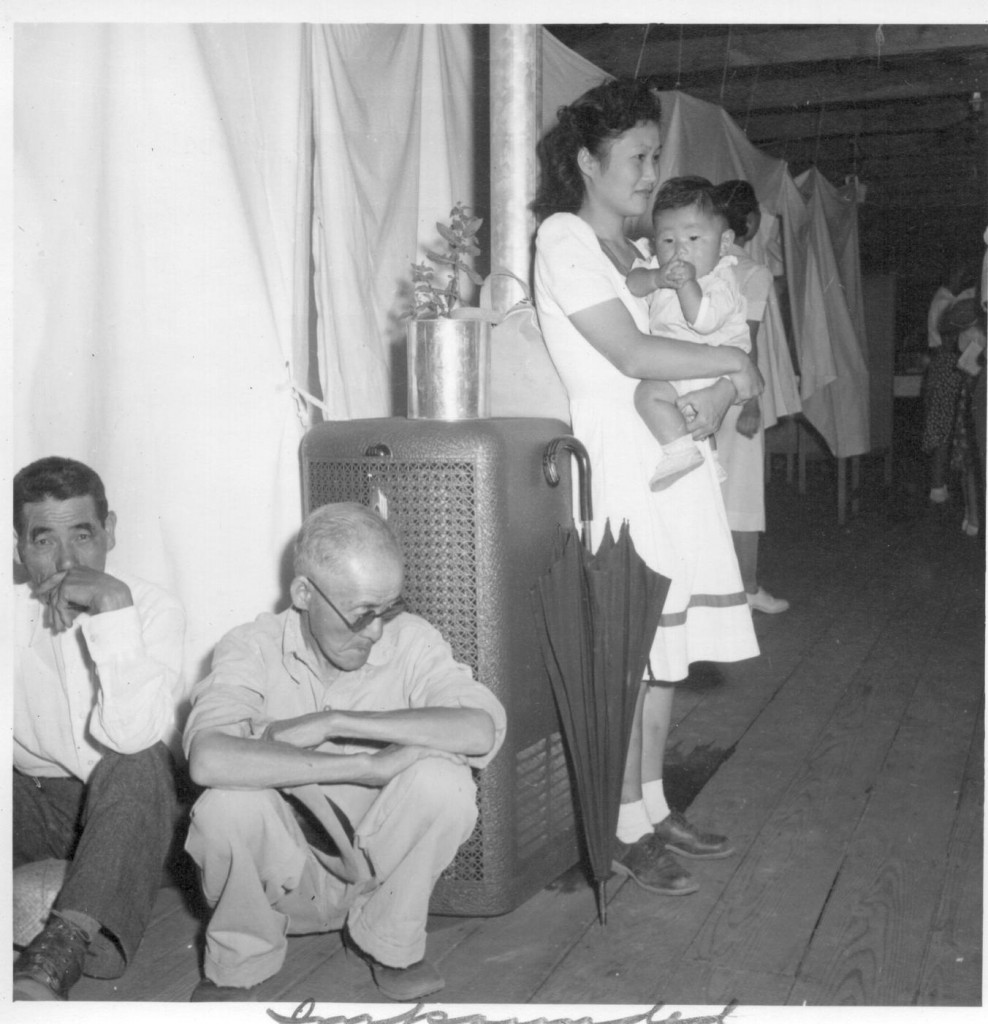

Barracks, Manzanar camp, California, WWII. Dorothea Lange

Barracks, Manzanar camp, California, WWII. Dorothea Lange

*

PHOTOGRAPHS, from top:

- A Japanese American unfurled this banner the day after the Pearl Harbor attack. Dorothea Lange photographed it in March 1942, just prior to the man’s internment. Wikimedia Commons.

- Minoru Yasui, the real-life hero of “Good Citizen.”

- George Taylor, author of “Good Citizen.”

- A typical interior scene in one of the barrack apartments at the Manzanar center in southern California. Note the cloth partition which lends a small amount of privacy. Collection: War Relocation Authority Photographs of Japanese-American Evacuation and Resettlement Series 8: Manzanar Relocation Center. Contributing Institution: The Bancroft Library. University of California, Berkeley. Photo: Dorothea Lange, June 30, 1942. Wikimedia Commons.