So last night, after the Super Bowl, I was channel-surfing. I’m not proud of it, but there you have it. Sometimes I think that’s the way the universe is trying to talk to me: If I happen upon the “Dog Whisperer,” I might conclude that I’m not calm and assertive enough (or maybe not submissive enough? Sometimes I get mixed messages). If “Ask This Old House” is working on someone’s water heater, then I immediately suspect that mine needs some lovin’.

So last night, after the Super Bowl, I was channel-surfing. I’m not proud of it, but there you have it. Sometimes I think that’s the way the universe is trying to talk to me: If I happen upon the “Dog Whisperer,” I might conclude that I’m not calm and assertive enough (or maybe not submissive enough? Sometimes I get mixed messages). If “Ask This Old House” is working on someone’s water heater, then I immediately suspect that mine needs some lovin’.

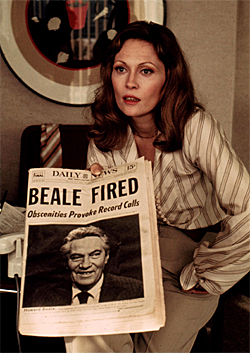

Anyway, as I was surfing, I fell in with Network, Paddy Chayefsky’s great 1976 satire about television and society, just before the Howard Beale speech, the “I’m mad as hell and I’m not going to take it anymore” speech. I knew it was coming and I waited for it, because to this day, it’s the single most subversive thing I’ve ever heard in a mainstream Hollywood movie. (Maybe you have others? We could make a contest of it in the comments.) And this time, it was a swift blow to the solar plexus.

I’ll give it a gloss, bit by bit:

I don’t have to tell you things are bad. Everybody knows things are bad. It’s a depression. Everybody’s out of work, or scared of losing their job. The dollar buys a nickel’s worth. Banks are going bust. Shopkeepers keep a gun under the counter. Punks are running wild, and nobody knows what to do. There’s no end to it.

Network is 1976, which means that inflation was on everyone’s minds, the newsreel footage of the guy pushing a wheelbarrow full of some worthless European currency to try to buy a loaf of bread somewhere lurked in newsreel memory. But yes, Depression. Fear. Not the punks yet, maybe, though our inner cities did get to that point during the Crack Era and maybe they will again. The line that hits home, though, is “nobody knows what to do.” Which really is where the fear comes from.

We know the air is unfit to breathe and our food is unfit to eat. We sit watching our TVs while some local newscaster tells us that today we had homicides and violent crimes, as if that’s the way it should be. We know things are bad. Worse than bad. They’re crazy.

Network was responding to the smog alerts of the ’60 and ’70s here, but this is one of the first mainstream suggestions that I can remember that the food industry (and I do mean industry) was a major mistake. Unfortunately, we now know that airborne pollutants can come from almost anywhere, that the Pacific isn’t large enough to insulate us from China, and our food problems are just as bad as ever, if not worse, as the industry has seized the government’s policy-making departments. A little Georgia peanut butter, anyone?

Everything is going crazy, so we don’t go out any more. We sit in the house, and the world we live in gets smaller. All we say is “Please, at least leave us alone in our living rooms. Let me have my toaster and my TV and I won’t say anything. Just leave us alone.”

Now he would add Internet to the list, I suppose. But what he’s really describing is the death of civil society. Which is what good urban planning seeks to forestall. Network is an “urban” movie, and I wonder now what its suburban audiences were thinking in 1976. Did they think that they could escape the bad stuff somehow, that if it was confined to the television, they could keep it at a bay, if they kept to the edges of the city and left the center to “them”? I think we forget sometimes now (if we are old enough to remember) how dicey the U.S. seemed in 1976, how dangerous, threatened from so many directions.

Well, I’m not going to leave you alone. I want you to get mad! … I don’t know what to do about the depression, the inflation and the crime. All I know is that first you’ve got to get mad!

The mad part. I won’t go into the rest; you probably remember; people sticking their heads out of apartment buildings in New York and hollering, “I’m mad as hell and I’m not taking it anymore.”

As blunt as it is as a political instrument, even a vague expression of anger is a powerful thing. It can change the political calculus in a hurry. And each of the political parties, the Republicans in my estimation more successfully than the Democrats, have tried to stoke it against the other one. So Howard Beale’s prescription was “right”: Passivity in a democracy is deadly.

But I want to focus on another sentence in this bit: “I don’t know what to do about the depression, the inflation and the crime.” Because, right, that’s a tough one. It came clear to me last week when I was listening to Paul Krugman: This is complicated stuff, our own, what, near-Depression? And unless you’ve read and digested your John Maynard Keynes, specifically his The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (1936) and maybe his Treatise on Money (1930), which I hasten to add, I haven’t, then it’s hard to understand, really understand, what’s going on, understand enough to have a strong opinion about the details. Krugman is a persuasive fellow, so what the heck, I defer to him, but it’s a judgment that I can’t easily verify by following the nitty-gritty of his arguments about how monetary policy affected the Great Depression.

But I want to focus on another sentence in this bit: “I don’t know what to do about the depression, the inflation and the crime.” Because, right, that’s a tough one. It came clear to me last week when I was listening to Paul Krugman: This is complicated stuff, our own, what, near-Depression? And unless you’ve read and digested your John Maynard Keynes, specifically his The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (1936) and maybe his Treatise on Money (1930), which I hasten to add, I haven’t, then it’s hard to understand, really understand, what’s going on, understand enough to have a strong opinion about the details. Krugman is a persuasive fellow, so what the heck, I defer to him, but it’s a judgment that I can’t easily verify by following the nitty-gritty of his arguments about how monetary policy affected the Great Depression.

In subsequent broadcasts, Howard Beale (and Peter Finch is terrific in the role) starts explaining the genealogy of various corporate take-overs of his network and what they mean. But you can sense the audience glazing over. HE can sense the audience glazing over — he runs through the whole thing very quickly. We just don’t have the patience for it, the background, the capacity for outrage at white-collar crimes and misdemeanors, at the undermining of the free press. We might be mad, but we’re not informed. We might believe Beale, but we aren’t likely to get too riled up about it.

Which is where Krugman thinks we are right now: we are catatonic in the face of the economic crisis because we don’t understand it, can’t find the bad guys exactly, can’t figure out what to do, know how profoundly dependent we are on the decisions and opinions of others.

Like Krugman. Or Keynes. Fortunately, neither of them are “pure” economists. By that I simply mean that though they both have/had a deep technical understanding of how economies work and why, they don’t think that a functioning economy is all there is. As Krugman said here last week, GDP by itself doesn’t mean anything… it’s the direction of the GDP — how do we deploy our resources, toward what end. Both of them believe that government can make the investments that are necessary to make the economy fairer and more just for those in it.

John B. Judis in the New Republic explains the full Keynesian position. He quotes Keynes, writing in 1939:

“The question is whether we are prepared to move out of the nineteenth century laissez-faire state into an era of liberal socialism, by which I mean a system where we can act as an organized community for common purposes and to promote social and economic justice, whilst respecting and protecting the individual–his freedom of choice, his faith, his mind, and its expression, his enterprise and his property.”

The answer has been, no, primarily because we haven’t found common purposes and we’ve resisted the “organized community.” Our default, at least ideologically, has been every man/woman for him/her self. Of course, it hasn’t worked out that way in reality — we find ways to cooperate, to achieve things together, even to address however haltingly some of the poverty/homelessness/hunger around us. Sometimes it’s grudging. It’s rarely unanimous. It’s as though something inside us wants to say, ‘don’t count on it.’ But our rhetoric (and by “our” I just mean the prevailing ideology) has been laissez-faire, or the way we say it today, “free market.” The market dictates our inequalities, our injustices, and we must obey. Otherwise, it’s “socialism.”

As Judis says, we are all Keynesians now, well, except for some free market die-hards, who STILL don’t want regulation of even the crazier markets, federal bailouts, federal stimulus packages, any of it. Keynes was pragmatic: What works? Classical economic theory clearly didn’t, especially in extreme times. But maybe not at all. Ever. Because even when our rhetoric was “free market,” we subverted it and its nasty social Darwinism (a perversion of Darwin’s actual science).

In Network I always thought that someone had forgotten to tell William Holden that he was in a satire. He played it so straight. Faye Dunaway is a crazy caricature: In bed with Holden, she quickly climbs on top, keeps talking business, has her usual premature orgasm, rolls off and keeps talking audience share. And he’s somehow “fascinated” with her? The stand-in for Edward R. Murrow? It’s always been the flaw in the film, for me at least, that incredible voice intoning the values of “news” while chasing the comely young Faye. But I can’t come up with an alternate line for him to follow. Maybe we need his moral authority? Even though he undermines it himself?

In the end, remember, the network makes a hit on Beale, the logical extension of the ratings game. The logical extension of the free market game is similar — if the ultimate aim is simply to accumulate wealth, to generate GDP, what it’s spent on doesn’t signify. The real security of the society isn’t in the market, it’s in our protection FROM the market — for everything from product safety to the unhealthy result of the accumulation of too much power in too few hands. For the market to be fair, someone has to make it fair. Namely, us.

And here the first step is the Beale Step: We have to get mad.