“At one time I thought that intelligent observation of facts was the best way of cheating the time allotted to us whether we want it or not; but now I have done with observation, too.â€

“Dreams are madness, my dear. It’s things that happen in the waking world, while one is asleep, that one would be glad to know the meaning of.â€

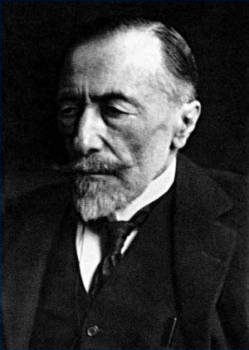

— Joseph Conrad, Victory

During this past week of “Mission Accomplished†ironies I have thought often of Joseph Conrad and his novel Victory, written before World War I began but not published until 1915. The book has nothing to do with war; if anything, it is one individual’s personal victory over his own skeptical detachment. In an author’s note Conrad said he had considered altering the title so as not to mislead readers, but decided against it because he thought Victory was the appropriate title for his story, based on “obscure promptings of that pagan residuum of awe and wonder which lurks still at the bottom of our old humanity.â€

During this past week of “Mission Accomplished†ironies I have thought often of Joseph Conrad and his novel Victory, written before World War I began but not published until 1915. The book has nothing to do with war; if anything, it is one individual’s personal victory over his own skeptical detachment. In an author’s note Conrad said he had considered altering the title so as not to mislead readers, but decided against it because he thought Victory was the appropriate title for his story, based on “obscure promptings of that pagan residuum of awe and wonder which lurks still at the bottom of our old humanity.â€

Do we have some bit of that glimmer of “awe and wonder†in our age of “shock and aweâ€? The one story I read at least once a year is “Heart of Darkness.†“And this also has been one of the dark places of the earth,†Marlow begins his tale. And we know what he means. Wherever we are as we read these words we know the green grass or concrete beneath us covers something in the past dark and bloody. A flight of a few hours can take us to one of several of those dark places. Our “here” can become a dark place overnight. No, Marlow says, the conquest of the earth is “not a pretty thing when you look into it too much.â€

What makes a long-dead writer our contemporary? Why do we feel such a direct connection to a nineteenth century Polish exile and sailor who began writing in English, his third language, after he turned forty? Polish drama critic Jan Kott wondered the same about Shakespeare. In Shakespeare Our Contemporary Kott writes that “Shakespeare is like the world, or life itself. Every historical period finds in him what it is looking for and what it wants to see.†And that is not because Shakespeare foretold things to come, but because, whatever the subject of his story, he filled the stage “with his own contemporaries.†Shakespeare aimed for “a reckoning with the real world.†For Kott, in mid-twentieth century Eastern Europe, it was “the struggle for power and mutual slaughter†in Shakespeare’s history plays that struck a chord. Kott also notes that in Conrad’s Lord Jim, the hero owns one book, a one-volume edition of Shakespeare. “Best thing to cheer up a fellow,†says Jim.

Why do Conrad’s novels and stories resonate with us in our time? Simply because conquest–of those inhabiting the earth, and, the earth itself, in all meridians–IS the story of our times. And, because, damned if they don’t cheer up a fellow like me!

Conrad in the Twenty-First Century: Contemporary Approaches and Perspectives, edited by Carola M. Kaplan, et al (Routledge 2005) provides good vantage on Conrad’s relevance. It is a huge collection of scholarly essays addressing the question “Why read Conrad now?†The essays are all over the map, discussing such topics as 9/11 and The Secret Agent and the war in Iraq and Nostromo, as well as Conrad’s representations of imperialism, globalization, postcolonial identity, racism, gender, immigration and mass media.

The last piece in the volume is an interview with Edward Said, who describes Conrad, in all his “worldly untidiness,†as a man “connected to the world in which he lived—I mean the essential world.â€

But it is J. Hillis Miller who, in his introduction to the volume, has the last word. He remembers being “enchanted†and “carried away†reading Conrad’s “Typhoon†as a kid. “I claim,†Miller writes, “that this kind of reading is a primordial and authentic way to be related to a literary work. All the superstructure of criticism, analysis, and commentary is erected on the foundation of such an ‘enchanted’ reading. If such a reading were not a common response to Conrad’s work, that work would not be worth talking about, in praise or in blame.â€

Conrad is enchanting, but also bleak, and deeply so. “Remember,†he wrote a friend, “that one is never entirely alone. Why are you afraid? And of what? Is it of solitude or of death? O strange fear! The only two things that make life bearable! But cast fear aside. Solitude never comes—and death must often be waited for during long years of bitterness and anger.†A heart in darkness, yes. But gloom of that foundational sort is also where Conrad finds “obscure promptings of that pagan residuum of awe and wonder which lurks still at the bottom of our old humanity.â€

There are days when that must be victory enough.