By Martha Ullman West

The School of Oregon Ballet Theatre delivered a promising and rewarding evening of ballet on Thursday night. It repeats on Sunday, and it’s well worth seeing even if you’ve no little hostage-to-fortune performing on the Newmark stage.

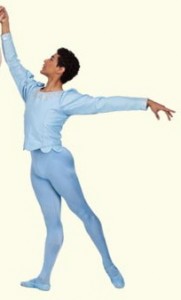

The evening began with a clean, musical performance of Balanchine’s Divertimento No. 15; Mozart’s gorgeous score, in a piano reduction, was played elegantly by David Saffert. As a curtain-raiser, Divertimento works well for professional companies, too: the solos of the Theme and Variations show off the skills of individual dancers, and the group sections – the opening Allegro and closing Allegro Molto – reveal a cohesive corps de ballet. Clearly, SOBT is training dancers to feed the company, men and women both. I was particularly taken by the dancing of Jordan Kindell, a company apprentice, in this and everything else in which he danced, as well as Chloe Shelby in the First Variation.

The evening began with a clean, musical performance of Balanchine’s Divertimento No. 15; Mozart’s gorgeous score, in a piano reduction, was played elegantly by David Saffert. As a curtain-raiser, Divertimento works well for professional companies, too: the solos of the Theme and Variations show off the skills of individual dancers, and the group sections – the opening Allegro and closing Allegro Molto – reveal a cohesive corps de ballet. Clearly, SOBT is training dancers to feed the company, men and women both. I was particularly taken by the dancing of Jordan Kindell, a company apprentice, in this and everything else in which he danced, as well as Chloe Shelby in the First Variation.

If Divertimento 15 shows off the pre-professional and upper-level dancers, Jerome Robbins’ Circus Polka, with Ring Master Kevin Poe flicking the whip (thank God) rather than cracking it, gives an excellent indication of the various levels of training, from the tallest kid in blue or green to the littlest one in pink. This was followed by a tidy accounting of an excerpt from Trey McIntyre’s Curupira, a percussive dance with the pointe shoes providing the music, much as they do in Dennis Spaight’s Crayola.

Faculty member Tracey Katona staged The Dance of the Knights from Romeo and Juliet as a showcase for boys of every size and stripe, with a few girls dashing back and forth across the stage. Wyatt McConville-McCoy, whom we’ve seen as the little prince in Balanchine’s The Nutcracker, and one of the smaller knights, is the winner of this year’s Elena Carter Scholarship, and I feel quite sure she approves; he clearly loves being on stage. The opening movement of Balanchine’s Serenade, with Kanoe Wagner as the girl who came late, just made me and several other audience members want to see the whole ballet, sooner rather than later. Balanchine made this ballet for students in 1934, creating a work that made modern dancers want to shift to ballet, it has such organic flow.

The evening closed with the premiere of Anne Mueller’s deliciously witty Carnival of the Animals: Brush Strokes in the Wild, and it’s a keeper. It’s no small thing to make a piece for students ranging from beginners to pre-professionals to music by Camille Saint-Saens that has piqued the interest of such choreographers as Michel Fokine and Christopher Wheeldon. Wheeldon’s version takes place in New York’s American Museum of Natural History after hours, and I loved it when I saw New York City Ballet dance it several years ago.

But Thursday night I also loved Mueller’s, which tells the story of a wildlife painter, danced by the very good-humored Justin Hughes, who is televised traveling the world like a National Geographic photographer, capturing animals in paint. Michael Mazzola’s clever set piece provides an occasional frame, for these animals are kept moving so fast they are mighty hard to “catch.”

Viable children’s ballets are not easy to do: They can descend into cloying cuteness. Mueller avoids that by giving her dancers organic movement based on research of how animals actually behave. Kangaroos, she says in program notes, scratch themselves frantically; giraffes fight with their necks. The most familiar music in the score is of course for the swan; Fokine used this music to make The Dying Swan, a solo for Anna Pavlova, which premiered in 1907, and over the decades it’s become the signature piece for several ballerinas, including Maya Plisetskaya, who once performed it twice in one evening in Portland at the auditorium formerly known as the Civic.

Mueller’s swans embrace life and each other – in the wild they do mate for life – in an eloquent pas de deux danced lyrically by Kindell and Kelsie Nobriga. And by creating roles for jellyfish, fish, sharks, starfish, as well as tortoises, roosters, a busybody of a magpie (danced by Emily Pihlaja), Mueller used a Cecil B. DeMille cast of seemingly thousands, not to mention every note of the score. If I saw the influence of McIntyre in the television hook, which he used for his Alice in Wonderland, and the deployment of silhouettes, which he and many choreographers use, I also saw much that was innovative and expressive of Mueller’s own personality in life and art.

There is one more performance, on Sunday afternoon. I’d go catch it.

PHOTO by Eric Griswold: Divertimento No. 15, choreography by George Balanchine ©The George Balanchine Trust.