On Saturday night Mr. and Mrs. Scatter went down to the industrial east Willamette waterfront, to Waterbrook Studio, the little theater-in-a-warehouse just north of the Broadway Bridge, to catch Poetry Off the Page.

It’s the latest in Eric Hull‘s Vox series of staged — I almost want to say composed — poetry readings. Composed, because it’s done by a chorus of actors in a chamber-musical fashion.

It’s the latest in Eric Hull‘s Vox series of staged — I almost want to say composed — poetry readings. Composed, because it’s done by a chorus of actors in a chamber-musical fashion.

Waterbrook is basically a room with an entrance area and a door leading to what serves as a green room for the performers. Somewhere around the corner, down a broad-plank floor, is a restroom. On Saturday the performance space had a few rows of folding chairs for the spectators, a lineup of music stands up front for the six performers, and three chairs to the side for the performers who occasionally sat a poem out. In other words: all the tools you really need to create some first-rate performing art.

Waterbrook is basically a room with an entrance area and a door leading to what serves as a green room for the performers. Somewhere around the corner, down a broad-plank floor, is a restroom. On Saturday the performance space had a few rows of folding chairs for the spectators, a lineup of music stands up front for the six performers, and three chairs to the side for the performers who occasionally sat a poem out. In other words: all the tools you really need to create some first-rate performing art.

It helps, of course, if you have some first-rate performers, and for this show Hull has cast impeccably. His six actors are adept at making their diction precise without squeezing the life out of the words. They are masters of rhythm, as crisp and casual at passing the ball as a good basketball team on a fast break, and beautifully cast for pitch, color and range. Grant Byington is the tenor, Gary Brickner-Schulz the baritone, and Sam A. Mowry the bass. The women — Adrienne Flagg, Theresa Koon, Jamie Rae — are similarly cast for their complementary vocal qualities.

What they do is this. They take a poem (twenty-five of them, actually), break it down to its component parts from stanza to line to syllable to vowel and consonant, settle on a rhythm, and deliver it as a group, sometimes passing it around phrase by phrase, sometimes word by word, sometimes in unison, sometimes as a soloist and chorus.

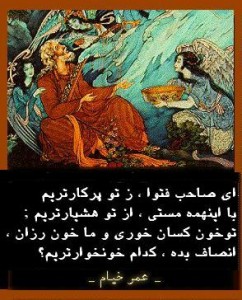

The evening begins with If I Told Him, a Completed Portrait of Picasso, a jaunty little number that brings out the meaning and wit in the sometimes dense and brackish work of Gertrude Stein; and ends with a remarkably staccato and refreshingly surprising rendition of Omar Khayyam‘s famous quatrain about “a loaf of bread, a jug of wine, and thou beside me in the wilderness”: imagine a Rubaiyat by Thelonious Monk.

The evening begins with If I Told Him, a Completed Portrait of Picasso, a jaunty little number that brings out the meaning and wit in the sometimes dense and brackish work of Gertrude Stein; and ends with a remarkably staccato and refreshingly surprising rendition of Omar Khayyam‘s famous quatrain about “a loaf of bread, a jug of wine, and thou beside me in the wilderness”: imagine a Rubaiyat by Thelonious Monk.

In between come poems classical (Lord Byron‘s She Walks in Beauty; Dylan Thomas‘s Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night), comical (Shel Silverstein‘s Sick; Hillaire Belloc‘s George, Who Played with a Dangerous Toy, and Suffered a Catastrophe of Considerable Dimensions) and lyrical (Li T’ai Po‘s Autumn River Song; e.e. cummings’ all which isn’t singing is mere talking — something of a statement of challenge for this performance, which so neatly combines the two).

Poetry Off the Page hovers somewhere between the literary and the musical (after all, isn’t all great writing musical at its core?), and it’s Hull who triangulates the precise position with his arrangements. I half-expected the script to be written like a musical score. It isn’t. Brickner-Schulz showed me his, and it’s typed out in full, with colored-marker lines to make his own parts stand out. That means that all the rhythm is internalized, settled during the hard work of rehearsal. What emerges is literate, entertaining, humorous, light yet sometimes touching. It’s not the silent hymn of reading a poem to yourself, or the magician’s drone of listening to the likes of W.H. Auden reciting his own work, or the rugby-scrum excitement of a poetry slam. It’s more like chamber jazz, smart and civilized and pleasurable.

Pleasurable for the performers, too. Need I mention that nobody’s doing this for the money? Afterwards, as audience and performers mingled on the way out, the word “fun” kept popping up. We all meant it, I think, a little more deeply. We just couldn’t come up with a better word.

Poetry Off the Page has three more performances, at 7:30 Friday, Saturday and Sunday nights, April 23-25.

To prepare you, here’s one of the poems, by Marge Piercy, from her collection Colors Passing Through Us (Knopf):

One reason I like opera

In movies, you can tell the heroine

because she is blonder and thinner

than her sidekick. The villainess

is darkest. If a woman is fat,

she is a joke and will probably die.

In movies, the blondest are the best

and in bleaching lies not only purity

but victory. If two people are both

extra pretty, they will end up

in the final clinch.

Only the flawless in face and body

win. That is why I treat

movies as less interesting

than comic books. The camera

is stupid. It sucks surfaces.

Let’s go to the opera instead.

The heroine is fifty and weighs

as much as a ’65 Chevy with fins.

She could crack your jaw in her fist.

She can hit high C lying down.

The tenor the women scream for

wolfs down an eight course meal daily.

He resembles a bull on hind legs.

His thighs are the size of beer kegs.

His chest is a redwood with hair.

Their voices twine, golden serpents.

Their voices rise like the best

fireworks and hang and hang

then drift slowly down descending

in brilliant and still fiery sparks.

The hippopotamus baritone (the villain)

has a voice that could give you

an orgasm right in your seat.

His voice smokes with passion.

He is hot as lava. He erupts nightly.

The contralto is, however, svelte.

She is supposed to be the soprano’s

mother, but is ten years younger,

beautiful and Black. Nobody cares.

She sings you into her womb where you rock.

What you see is work like digging a ditch,

hard physical labor. What you hear

is magic as tricky as knife throwing.

What you see is strength like any

great athlete’s. What you hear

is still rendered precisely as the best

Swiss watchmaker. The body is

resonance. The body is the cello case.

The body just is. The voice loud

as hunger remagnetizes your bones.

*

ILLUSTRATIONS, from top:

— The Vox logo.

— Brunnhilde, George Grantham Bain Collection, U.S. Library of Congress

— An illustration from Divan-e-Khayyam, Iran.