Portland loves process — a politician here can barely duck out for coffee without holding several public meetings first to thrash out which coffee shop she should hit in which geographically underserved corner of the city — and that extends to its arts scene.

Lectures, tours, workshops, open rehearsals: If it’s a behind-the-scenes peek, we’re there. It’s not enough just to see the finished project. We want to know how it got there.

Lectures, tours, workshops, open rehearsals: If it’s a behind-the-scenes peek, we’re there. It’s not enough just to see the finished project. We want to know how it got there.

What was the idea? How was it built? What were the stumbling blocks? Was getting there really half the fun?

In the visual arts, something else kicks in, too: sweet reassurance.

Galleries and museums intimidate a lot of people. They don’t know the language. They might know what they like, but they suspect the cognoscenti would laugh at them. In galleries, they think they’re getting the once-over (and in a few, they are): Is this person a potential buyer? Does she count? Is she worth my time?

It’s not so much that people are afraid of wrestling with tough ideas, it’s that they’re afraid they don’t know the rules. They’re not specialists — and in the minds of the many, the art world has become the province of the anointed few. (In certain rigorously theoretical cases, of course, this is true.) Add to all this the sense of mystery — the popular idea that with artists, something magical happens, beyond the ken of mortal souls — and it’s little wonder that fear keeps people outside the gallery doors.

In fact, the actual making of art is usually a tactile, pragmatic, hands-on thing; down-to-earth in a sometimes literal sense. For all the metaphorical calisthenics in writing about art, artists themselves tend to be practical problem-solvers: What is this thing that’s wormed inside my head, and how can I work it out? Most artists grapple with chance and improvisation more than most of the rest of us, but the good ones do it with method and structure. In spite of C.P. Snow’s famous lament in The Two Cultures (or maybe in support of it), the worlds of art and science aren’t all that far apart, at least in a rudimentary sense. Both involve hypothetically based searches for truth, and in that search both find beauty.

So let’s take the pressure off and take a relaxed look at how this art stuff really works. That’s part of the idea behind Portland Open Studios, the annual fall tour of artists’ studios across the greater Portland area. In its 10th year, the event includes 100 studios (they’re juried in) and runs the next two weekends: October 10-11 and 17-18. Most studios are open both weekends; the Web site has details.

So let’s take the pressure off and take a relaxed look at how this art stuff really works. That’s part of the idea behind Portland Open Studios, the annual fall tour of artists’ studios across the greater Portland area. In its 10th year, the event includes 100 studios (they’re juried in) and runs the next two weekends: October 10-11 and 17-18. Most studios are open both weekends; the Web site has details.

It’s always fun to see where other people work. I visited three studios before the kickoff, and each represented a different approach to the artist’s workspace.

Bonnie Meltzer‘s studio in North Portland is a storybook sort of place, a small building steps away from the back door of an old farmhouse on a double lot that also holds gnarled fruit trees and a pretty terrific vegetable garden. The studio strikes a balance between orderly and cluttered, with all sorts of tools that a home handyman would be comfortable with, and a motley collection of globes destined to find their way at one point or another into her mixed-media works. A deck outside the studio is set up for sawing and bashing at big pieces of stuff.

Encaustic artist Andrea Benson works from a small studio at Troy Studios, a big brick former commercial laundry building in industrial Southeast Portland that’s home to about 25 artists. She can bike or walk there from her home, and likes having a separate space. A few blocks away, Mar Ricketts, whose fabric pieces range from aerodynamic kites and mobiles to temporary structures for big outdoor events, works in a big single-story space that allows plenty of floor room for laying out his sometimes gargantuan pieces. His studio isn’t a recycled industrial space: It is an industrial space.

Benson’s small upstairs studio is well-ordered, its walls lined with finished works and soft light (not enough, she laments) filtering in through the windows. She has a couple of comfortable chairs, a little table where she can make her coffee, a bigger worktable where among other tasks she can mix her encaustics, an old method based on beeswax and pigment (it’s sometimes called hot-wax painting), which she turns into candle-like clumps. “You can buy all the encaustic materials ready-made,” she says, “but it’s so expensive I never do it.”

Instead, like a medieval guild worker, she crafts her own, working it into her paintings over wood surfaces. Besides doing her own work in the studio, she also teaches classes in encaustic painting there. Maybe the studio tour will net her some students, she says.

Instead, like a medieval guild worker, she crafts her own, working it into her paintings over wood surfaces. Besides doing her own work in the studio, she also teaches classes in encaustic painting there. Maybe the studio tour will net her some students, she says.

Encaustic is a process she finally came home to after messing around with all sorts of hands-on forms: ceramics, photography, etching, intaglio. “I really had a crisis of object-ness,” she says of her beginning days in ceramics. “Why bring more big clunky objects to the world?”

Encaustic, she discovered, was different, at least for her — more creative, more malleable: “It’s like a griddle. You’re mixing all sorts of stuff. It’s really a lot like cooking.”

For the past year or so she’s been working on something she calls The String Series, a succession of paintings in which things unravel and regenerate at the same time. The paintings have stories, but they don’t spin out in words. The wax, which she often uses for hands and arms, gives the surfaces an almost three-dimensional texture and a shine that makes the encaustic sections leap out.

And the wax lets her rework things. “The act of covering things up and re-exposing them is a place where really interesting things happen,” she says.

Benson’s journey to the Open Studios weekend (this is her third go-round) has been circuitous. She earned an undergraduate art degree in 1981 from Penn State, and moved to Portland in 1984. She spent time as a cook and caterer, then earned a second bachelor degree, this one in interior design, from Marylhurst University and followed that with eight years of doing corporate design work.

Finally, she says, “I sort of decided, ‘When am I going to actually do art? If not now, when?'”

Fear, she thought, was keeping her from doing it. Fear, and an unhealthy streak of self-criticism. “I made the decision that I was going to shut down my inner critic. At least for a year. There’s that thing that jumps out and ambushes you.”

Fear, she thought, was keeping her from doing it. Fear, and an unhealthy streak of self-criticism. “I made the decision that I was going to shut down my inner critic. At least for a year. There’s that thing that jumps out and ambushes you.”

Now, here she is. Maybe not rich, maybe not famous. But unambushed. And working on something that truly engages her.

“Before I even start to work I do drawings, and get a general composition set,” she says. “Then I get to this point where I know I’m going to jump off. I establish structure, and then it becomes improvisation. It’s that combination of structure and improvisation that’s interesting to me.”

Like Benson, Ricketts landed where he didn’t begin. He got his architecture degree from the Pratt Institute in New York and figured he was on his way.

“I thought, ‘OK, I’m going to do contemporary architecture’ — thought I knew all about it,” he says.

But something happened. He’d grown disillusioned with the direction of the mainstream architecture world. He found himself thinking about “new potentials of using lighter materials, working more organically.”

And … well, he’d always liked kites.

He started thinking about aerodynamics, and airplane wings, and the kinds of structural tension that can support a lot of weight without a lot of underpinning. He began to think like an engineer, like a designer/craftsman, like a master builder. In a way, like Leonardo or William Morris.

He started thinking about aerodynamics, and airplane wings, and the kinds of structural tension that can support a lot of weight without a lot of underpinning. He began to think like an engineer, like a designer/craftsman, like a master builder. In a way, like Leonardo or William Morris.

“Do things beautifully, scientifically, minimally,” he says. “That’s important for our time. It’s a real marriage of art and science, just like architecture. I believe that everything we live with could be beautiful.”

So he started with kites, getting patents on some structural advances. After Pratt, he started his business in Massachusetts. Then he moved it to Madison, Wisconsin, lured by a winter kite festival on an iced-over lake in the middle of town. Finally, five years ago, he landed in Portland.

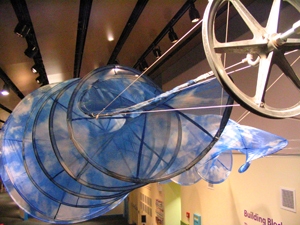

Kites begat mobiles. He started doing kite performances, and that led to building fabric stage sets for outdoor performances, including the Pickathon indie roots music festival near Happy Valley, where his temporary fabric city uses 80,000 square feet of fabric. He does a lot of site-specific work, designing and building interior and exterior fabric sculptures for hospitals, children’s museums, libraries.

He works big: 350-foot sails at a museum in St. Paul, Minnesota; a spiral sculpture 30 feet long and 8 feet tall at another kids’ museum in Chicago. He works with bicycle gears and pulley wheels. He uses terms like “tension suspended air foil.” He works around the world.

He thinks environmentally. “Architecture uses 50 percent of our natural resources,” he says, and although I have no way of checking that figure, considering source-to-site costs, he could be right. He pays extra so he can use nontoxic fabrics.

And he thinks about the future. “We’re heading more and more toward temporary structures. Temporary gathering,” he says. “Permanent structures are so expensive. Temporary structures can be more ecological, and can also be as comfortable.”

And he thinks about the future. “We’re heading more and more toward temporary structures. Temporary gathering,” he says. “Permanent structures are so expensive. Temporary structures can be more ecological, and can also be as comfortable.”

He says all of this standing in a very old, very permanent industrial space big enough to handle the sorts of projects he works on. That’s not necessarily a contradiction. Ricketts fabricates ideals. And as much as his work is futuristic, it also looks longingly back to the past, to a time when art and design and just plain living were a more unified theory.

Portland Open Studios is also about bridging a gap — about bringing artists and art viewers into a closer understanding of one another. “It’s not edgy,” as Benson puts it. “It definitely has a more common-people, middlebrow audience.”

On the other hand, as she also says, the quality of work goes up every year, with an intriguing blend of gallery-represented artists and those who don’t have galleries. It’s democratic, which means that ideas can come from the sidelines and surprise you. And some sophisticated work is on view, a lot of it working the soil of that fertile ground where art and craft meet.

Besides, hopping from studio to studio is fun. Who knows what you might find?

————————————————————–

PHOTOS, from top:

— Mar Ricketts, builder of high-design kites and other fabric extravaganzas, in his studio.

— Andrea Benson works with ideas of unraveling and regenerating in her encaustic paintings.

— Bonnie Meltzer puts cut-up credit cards inside a cornucopia.

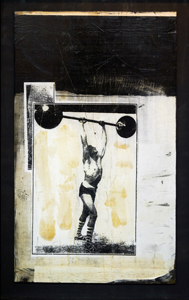

— “U Gotta B Strong,” by Mark Randall.

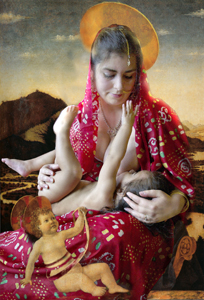

— Sabina Haque’s “Indian Madonna and Child.”

— One of Mar Ricketts’ floating spiral gear-and-fabric sculptures.