By Laura Grimes

It’s raining and the sky is pretty much a solid dull gray. Gray upon gray. Rain upon rain. End upon end. But the sky doesn’t have to be that dull.

The Pantsless Brother must have seen something different out his window. He sent me this note:

I’m looking out at the sky over the water as the evening fades and all I see is Turner.

Could he have been thinking of this painting?

The Fighting Temeraire by J.M.W. Turner, 1839

Oil on canvas

National Gallery, London

That brilliant expanse of sunset sky is saying goodbye to a famous warship that’s seen its last good fight and being carted off on its last voyage to be broken up. Broad, colorful strokes know their bigness and strikingly evoke a sense of loss. The canvas gives room to all that the sky has to say.

A little while later I got this note from The PB:

Now the sky is like Whistler, dark and brooding …

James Abbott McNeill Whistler painted a series he called Nocturnes. He titled many of his pieces with references to music to draw analogies to both a more abstract art form that didn’t have narrative or moral content and to the tones, harmonies and compositions he explored. He believed in art for art’s sake, separate from emotions and without sentimentality.

In the Nocturnes, Whistler developed a special technique where he thinned paint and applied it to the canvas in broad strokes. He once said, “Paint should not be applied thick. It should be like breath on the surface of a pane of glass.”

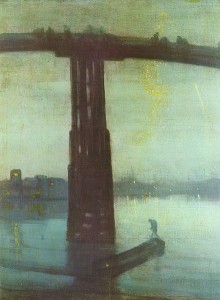

James Whistler

Nocturne in Blue and Gold: Valparaiso Bay (1866)

Wikimedia Commons

James Whistler

Nocturne: Blue and Gold – Old Battersea Bridge (1872-1875)

Oil on canvas

Tate Britain, London

Wikimedia Commons

According to Tate Britain’s website, the display caption in February 2010 with the Battersea painting said Whistler wrote,

… when the evening mist clothes the riverside with poetry … tall chimneys become campanili [bell towers] and the warehouses are palaces in the night and the whole city hangs in the heavens and fairy land is before us.

James Whistler

Nocturne in Black and Gold, the Falling Rocket (1875)

Oil on panel

Detroit Institute of Arts

Wikimedia Commons

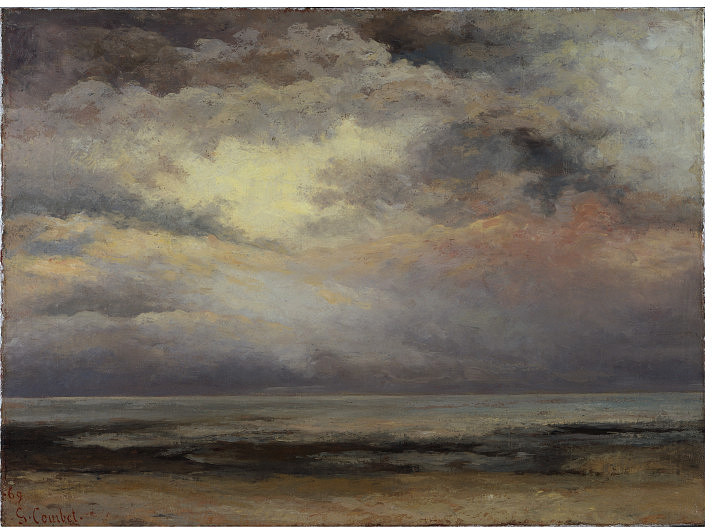

The PB and I talked more about Turner’s paintings on the phone. Some comment about the subtle color changes, the play of light between sky and water and the quiet bigness of it all made me remember a small note I put in my notebook. I couldn’t remember it exactly, so later I fetched it and sent it to him. It was about Gustave Courbet. It turns out Whistler spent some time with Courbet and admired his work.

Gustave Courbet

L’Immensite (1869)

Oil on canvas

Victoria and Albert Museum, London

The note I jotted down?

A critic praised its portrayal of ‘the grand impassiveness of nature.’

Sky doesn’t get much better than that. It might be impassive, but it has a lot to say.