On Saturday morning I picked up my newspaper and saw on the front page a photo of President Obama, smiling easily and looking down at, but not down on, Hugo Chavez. The American president is shaking hands with the Venezuelan president, a man who ordinarily makes great political hay from being seen and heard as a bellicose opponent of the United States and its political leaders. Chavez, too, has the sort of smile that seems genuine and not faked for the cameras (although who can say for sure in either case — these are politicians), and a semicircle of unnamed onlookers at the Western Hemisphere summit meeting in Port of Spain, Trinidad and Tobago, seems equally charmed.

Yes, charmed. And I thought, this is policymaking outside the channels of policy. Here, in Obama, is a man utterly at ease inside his own skin. That’s why people respond to him. Because he’s comfortable with himself.

Yes, charmed. And I thought, this is policymaking outside the channels of policy. Here, in Obama, is a man utterly at ease inside his own skin. That’s why people respond to him. Because he’s comfortable with himself.

My eye lingered on this photograph because the night before I’d seen Peter Morgan’s play Frost/Nixon at Portland Center Stage, and if there ever was a leader who was uncomfortable inside his own skin, it was Richard Nixon. Actor Bill Christ, in Rose Riordan’s smooth and entertaining production, makes this as clear as can be. He offers a Nixon who is inordinately intelligent and funny in the driest possible way, but who’s so clumsy he gives even himself the heebie-jeebies. He’s not smooth, he’s not sexy, he can’t do small talk. If he were a language he’d be German, not French. Nixon was actually savvier even than JFK about the power of the television camera but he couldn’t take advantage of it because he didn’t have the goods: He could only mitigate the camera’s effect by understanding how it works. Nixon knew that in the charm game he would always be an outsider looking in, and he resented it deeply. It fed his combativeness, his sense of the Other, of us versus them, of his bitterness of the East Coast elite’s patronizing of him, of being the guy who knew all the strategies and did all the dirty work but was barely allowed in the game.

I was young when Nixon bulldozed back into power in 1968 with his “secret plan to end the war,” and I despised him with all the moral certainty that only the young can summon. It was an extension of my detestation for Lyndon Johnson: How could these men be such liars and murderers? Over the years I’ve come to think of both instead as tragic figures. Here were leaders who could have been great — indeed, who were great in certain ways — but who were destroyed by their own hubris. Over time I might change my mind about this, too, but I now think of Nixon and Johnson as tragic in a way that George W. Bush can never be, because Bush lacked the capacity for greatness: His limitations made him instead something on the order of an oversized and disastrously effective school bully.

In a way Frost/Nixon is a latter-day reclamation project for Nixon’s reputation, not so much an apology as an attempt at explanation. We tend to make caricatures of historical figures, and Nixon has been pretty much cast as the shifty-eyed guy with the 5 o’clock shadow and the bloody hands who gave us the suffix “-gate” to append to any scandal large or small. The truth was more complex, so much so that historian Garry Wills was able to refer to Nixon, straight-faced, as “the last liberal.” Nixon can never be a hero in my lexicon — his sins are too deep — but Morgan’s play helps restore his stature: He was a man to be reckoned with, almost in a Shakespearean way. The television personality David Frost might have “won” their showdown — under his prodding Nixon “confessed,” if that’s the proper word for his contorted contextualization of events — but in a larger sense the victory was Nixon’s for reasserting the importance of his engagement with the world.

Still, he was a clumsy man, uncomfortable in his skin. Does that make a difference? Leadership depends to a certain degree on personal charisma, and some politicians have far more of it than others. Charisma can give you a free pass, or at least a cut-rate ticket, but it’s up to you how you use it. John F. Kennedy and Bill Clinton had it in aces, and in both cases it fed a moral laziness that hurt their presidencies. Locally, Neil Goldschmidt dazzled, and he slowly rotted from the inside. By the time I saw Hubert Humphrey in the flesh he seemed despite his natural optimism to be neither happy nor much of a warrior, caught as he was in his 1968 campaign against Nixon between his desire to be president and his unwillingness to denounce LBJ’s handling of the Vietnam war and assert a plan and identity of his own. Early in my journalistic career I was familiar with Washington state politicians, and the state’s two powerful senators split the difference in terms of charm. Warren Magnuson oozed the stuff. Scoop Jackson couldn’t charm the skin off a molting snake. Each managed in his own way to exert a huge amount of influence. I never met Jimmy Carter but I watched him play a crowd in his 1976 presidential campaign, and in person he had enormous vitality and charisma, which didn’t seem to help his presidency but may help account for his continuing stature in his post-White House days.

And of course, who could seem more awkward than Abraham Lincoln, as a contemporary journalist, a visiting Brit named William Howard Russell, recorded after first seeing the president in 1863:

“…(T)here entered with a shambly, loose, irregular, almost unsteady gait, a tall, lanky, lean man, considerably over six feet in height, with stooping shoulders, long pendulous arms, terminating in hands of extraordinary dimension, which, however, were far exceeded in proportion by his feet.”

Not exactly a charmer. Yet somehow, Lincoln transformed himself into the greatest president we’ve had. Charm is a wonderful political tool, and as that photo of Obama disarming Chavez attests, it can work wonders. But every presidency, Nixon’s included, has its highs and lows, and its success or failure comes over the long haul. Maybe what counts more than charm is, as Martin Luther King Jr. put it, the content of your character. And there’s nothing like the trials of leadership to test that.

********************

William Shakespeare is still vivid in our imaginations for a lot of reasons, and one is his penetrating examinations of the nature of power and its effects on the lives of those who wield it. So a production of his Richard II seems like an apt companion to Frost/Nixon, and Carol Wells has good things to say about Northwest Classical Theater Company‘s new version in her review for The Oregonian. And this morning in the O, Marty Hughley ups the ante in his excellent interview with JoAnn Johnson, who directed this production, which happens to feature an all-woman cast.

William Shakespeare is still vivid in our imaginations for a lot of reasons, and one is his penetrating examinations of the nature of power and its effects on the lives of those who wield it. So a production of his Richard II seems like an apt companion to Frost/Nixon, and Carol Wells has good things to say about Northwest Classical Theater Company‘s new version in her review for The Oregonian. And this morning in the O, Marty Hughley ups the ante in his excellent interview with JoAnn Johnson, who directed this production, which happens to feature an all-woman cast.

How come? Well, payback might be one reason: Don’t forget, in Shakespeare’s day all the roles, including the heroines, were played by men. But this runs deeper. Johnson, who put in years at the Oregon Shakespeare Festival and is a fine actor as well as a perceptive director, tells Hughley that one reason the project appealed to her was overtly political:

“I was a Hillary supporter. And as I followed her campaign, I was appalled by our culture’s discomfort with hearing a woman speaking the language of power, of having all this talk about using power in the world coming out of the mouth of a woman.”

So she gave them Shakespeare’s voice, which, she says, opened up new areas of emotion and possibility for the woman actors. As the project progressed she discovered that while the casting was unconventional, the play itself took over. “Every time I was tempted to get tricky with it and try to make it do something it maybe wasn’t intended to do, I’d run into big problems,” she told Hughley. So, she let the play itself take over and do what it wanted to do.

Power is power, no matter who holds it. Maybe that’s the point.

********************

The idea of women playing men’s roles onstage isn’t new. Daring actresses have tackled the great Shakespearean leading roles over the years, and in Jo Walton‘s 2007 novel Ha’Penny — the second in her trilogy of alternate-history novels about a fascist takeover of England during the Second World War — an essential feature of the plot is the London stage’s mania at the time for cross-dressing productions, a trend that proves to be boffo at the box office.

The idea of women playing men’s roles onstage isn’t new. Daring actresses have tackled the great Shakespearean leading roles over the years, and in Jo Walton‘s 2007 novel Ha’Penny — the second in her trilogy of alternate-history novels about a fascist takeover of England during the Second World War — an essential feature of the plot is the London stage’s mania at the time for cross-dressing productions, a trend that proves to be boffo at the box office.

In Ha’Penny Viola Lark, a fictional stand-in for one of the infamous Mitford sisters, is a London actress who is cast to star as Hamlet in a major production. It’s 1949, and her big moment arrives at the same time as Adolf Hitler (who is still alive, and pretty much in control of all of Europe, though the Soviets are still holding out) and the fascist prime minister (whose power grab is detailed in the first book of the trilogy, Farthing) show up for opening night. Of course, there’s a bomb plot ….

Walton’s trilogy — the final volume, which I haven’t read, is Half a Crown — is a fine cross between the traditions of the old-school British murder mystery and thriller on one hand and the much more harrowing territory of writers such as George Orwell on the other. In Farthing England has made a separate peace with Hitler, ensuring its independence at the price of the rest of Europe. (Isolationism has won the day in the United States, where Charles Lindbergh is president.) And while life just seems to roll on, life gets worse and worse for Jews, homosexuals, Gypsies, anyone on the “outside.” Everything downward is accelerated (there’s one funny reference to a new novel about farm animals, 1974) and the worst creeps steadily forward, in little increments.

What’s creepy, and effective, about these novels is that they’re only a half-turn of the screw from reality. Power is subtle, and power is hard. And it will take anything it can get, or anything that ordinary peoiple are willing to give it.

Charming thought, isn’t it?

********************

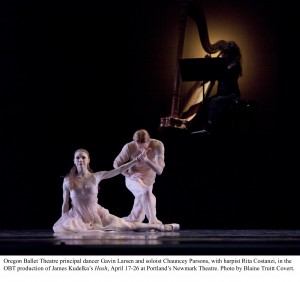

Enough of politics. How about a costume drama? In my review of Oregon Ballet Theatre‘s new program Left Unsaid for The Oregonian (and do see this show if you can: It’s lovely, and it continues through Sunday) I got a little snippy about the costumes for William Forsythe’s The Vertiginous Thrill of Exactitude:

Enough of politics. How about a costume drama? In my review of Oregon Ballet Theatre‘s new program Left Unsaid for The Oregonian (and do see this show if you can: It’s lovely, and it continues through Sunday) I got a little snippy about the costumes for William Forsythe’s The Vertiginous Thrill of Exactitude:

I have a tough time getting past Stephen Galloway’s odd costumes, which keep grabbing my eye while I should be watching the dancing. The color scheme – vivid orange for the men, lily-pad green for the women – is one thing. But the strange hoops around the women’s midsections – they look less like tutus than like the rims of 10-gallon cowboy hats – effectively chop the women in half and leave me constantly wondering whether I need new bifocals.

Martha Ullman West, a friend with greater knowledge than my own about such things, informs me that those hat brims are actually called “saucer tutus” — I’m not sure whether of the flying variety. And she points out that they are much more distracting in the relatively intimate Newmark Theatre, where the current program is playing, than they were a year a half ago when the same dance was performed in the much more cavernous Keller Auditorium. Fair enough. Sometimes size does matter.

That’s really the only bad thing I had to say about this adventurous and beautifully performed program, and it’s only fair to point out again how wonderful Christine Darch’s costumes are for the world premiere of James Kudelka’s ballet Hush: You can get a taste of them from the picture here and the picture at the very top of this (getting longer by the minute — are you still here?) post. Bravo.

********************

Finally (!), I spent Monday evening at Southeast Portland’s Theater! Theatre!, where this month’s FreshWorks reading by Portland Theatre Works was onstage. Maybe you don’t know this group, but in these days of our Slightly-Less-Than-Great-Depression (it seems wrong to call it the Good Depression) it’s one of the best theater deals in town. Free is a very good price.

PTW does new scripts, and new scripts exclusively. Sometimes it workshops them. More often — and this is what constitutes the FreshWorks series, which is usually on the third Monday of the month — it gives a single reading, by professional actors, of a new script. Each of the performers has seen the script (they usually get a copy about a week in advance) but there are no rehearsals, meaning that the night of the reading is the first time the cast has actually got together. Remarkably, it usually works out OK. And the playwrights get to hear what they’ve written first-hand, the way an audience does. That can be valuable in figuring out what is and isn’t working.

Monday’s script was George Taylor’s gentle comedy Next Train to Moscow, which riffs on Chekhovian characters and themes but is set, a la Friends, in a modern-day coffee shop. A twist, which Taylor revealed at the end: The characters are based on the characters in Peanuts, 40 years later. I didn’t catch it, and it really doesn’t matter: The play stands perfectly well on its own. But maybe I should have figured it out from the stage direction instructing the failed classical pianist to play a little jazz — maybe some Vince Guaraldi. You’re an odd duck, Charlie Brown.