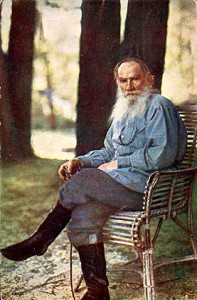

Reading William J. Broad’s fascinating report in the Science section of Tuesday’s New York Times about a possible breakthrough in world rice production got me thinking about Leo Tolstoy‘s masterful War and Peace, which I’ve been enjoying, in small gulps of 20 to 40 pages a sitting, in Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky’s lively 2007 translation.

Reading William J. Broad’s fascinating report in the Science section of Tuesday’s New York Times about a possible breakthrough in world rice production got me thinking about Leo Tolstoy‘s masterful War and Peace, which I’ve been enjoying, in small gulps of 20 to 40 pages a sitting, in Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky’s lively 2007 translation.

For all of the novel’s cinematic scope and dense cultural and moral observation (the closest thing to an American equivalent of this amazing piece of writing, which Tolstoy himself referred to as an “epic” rather than a novel, is Herman Melville‘s similarly discursive Moby-Dick), Tolstoy could draw a character and an intimate conversation like nobody’s business: Reading this translation, you feel like you’re in the room, observing with the invisible narrator himself, smiling or shuddering at facial expressions, nodding in agreement with Tolstoy’s acute descriptions.

So let’s drop in, early in the going, on a conversation about the old roue Count Kirill Vladimirovich Bezukhov, who is on his deathbed and has no legitimate immediate heirs, although illegitimate ones are apparently scattered across Russia like seed from a flock of migrating birds. One of this prodigious offspring, the fine, fat, clumsy bear of a fellow Count Pyotr Kirillovich, or Pierre, looks to be on the ascent:

“Princess Anna Mikhailovna mixed into the conversation, clearly wishing to show her connections and her knowledge of all the circumstances of society.

” ‘The thing is,’ she said significantly and also in a half whisper. ‘Count Kiril Vladimirovich’s reputation is well-known … He’s lost count of his children, but this Pierre was his favorite.’

” ‘How good-looking the old man was,’ said the countess, ‘even last year! I’ve never seen a handsomer man.’

” ‘He’s quite changed now,’ said Anna Mikhailovna. ‘So, as I was about to say,’ she went on, ‘Prince Vassily is the direct heir to the whole fortune through his wife, but the father loved Pierre very much, concerned himself with his upbringing, and wrote to the sovereign … so that when he dies (he’s so poorly that they expect it at any moment, and Lorrain has come from Petersburg), no one knows who will get this enormous fortune, Pierre or Prince Vassily. Forty thousand souls, and millions of roubles. I know it very well, because Prince Vassily told me himself. And Kirill Vladimirovich is my uncle twice removed through my grandmother. And he’s Borya’s godfather,’ she added, as if ascribing no importance to this circumstance.”

Fine, witty writing. But what’s it got to do with the price of rice in China? Hold on. We’ll get there.

Forty thousand souls, the princess counts among the old man’s fortune. That means 40,000 serfs — in effect, slaves — whose lives and labor are in the power and patronage of a single man. Tolstoy finished writing War and Peace in 1868, seven years after the emancipation of Russia’s serfs; America’s Emancipation Proclamation was even fresher news. But the novel is set during the Napoleonic wars, from 1805 through 1812. And at the beginning of that period the world population was about 1 billion (up from a scant 1 million in 10,000 B.C.E.), or roughly one-seventh of today’s estimate of 6.7 billion. So with the same equivalent of the population, Count Bezukhov today would have directly controlled the destinies of 280,000 men, women and children — an astonishing figure, even in the contemporary world of runaway wealth and the new Russia of extreme fortunes got fast and furious. And how does a master feed 40,000, or 280,000, or 6.7 billion souls?

Forty thousand souls, the princess counts among the old man’s fortune. That means 40,000 serfs — in effect, slaves — whose lives and labor are in the power and patronage of a single man. Tolstoy finished writing War and Peace in 1868, seven years after the emancipation of Russia’s serfs; America’s Emancipation Proclamation was even fresher news. But the novel is set during the Napoleonic wars, from 1805 through 1812. And at the beginning of that period the world population was about 1 billion (up from a scant 1 million in 10,000 B.C.E.), or roughly one-seventh of today’s estimate of 6.7 billion. So with the same equivalent of the population, Count Bezukhov today would have directly controlled the destinies of 280,000 men, women and children — an astonishing figure, even in the contemporary world of runaway wealth and the new Russia of extreme fortunes got fast and furious. And how does a master feed 40,000, or 280,000, or 6.7 billion souls?

Continue reading Feeding the masses: What would Tolstoy do?