Cultural types who complain that the mainstream media never pay attention to the arts just haven’t been reading the news pages, where it’s theater, theater, theater, hour after hour, day after day.

No figure in history is more honored in our news coverage than the revolutionary Russian set designer Grigori Potemkin, and his ingeniously adaptable Potemkin Villages are inhabited for our entertainment purposes by similarly interchangeable Potemkin People.

No figure in history is more honored in our news coverage than the revolutionary Russian set designer Grigori Potemkin, and his ingeniously adaptable Potemkin Villages are inhabited for our entertainment purposes by similarly interchangeable Potemkin People.

Somewhere back there behind these pop-up people and prop-up set pieces a real world no doubt languishes, waiting for its moment to step into the spotlight and state its case that a little attention must be paid. Never mind. The comedy onstage is just too delicious to abandon for the dreary drama of the broken-down kitchen sink.

Herewith, program notes on just one new show in a typically hectic season:

THE FALL AND RISE OF THE SHARP-TONGUED CONGRESSMAN

A Comedy in Too Many Acts

“You lie!” the gentleman from South Carolina shouted as the President spoke and the greedy cameras rolled.

And the House came tumbling down.

And the House came tumbling down.

On Tuesday, United States Representative Joe Wilson, Republican from the Sovereign State of Secession, was formally rebuked by his fellow inmates for breaking up President Obama’s speech to Congress on health care reform with an outburst of what appeared to be actual passion. Following the traditional pattern of this highly ritualized form of theater, Wilson than prostrated himself before the President in shame, apologizing for his transgression and begging forgiveness. According to the time-honored script the Wise Leader graciously absolved him, with a parting, “Go, and sin no more.”

But unusually — don’t you just love it when a performance breaks through the fourth wall, and we all get pulled into the action? — that wasn’t enough. The neat pattern didn’t address Wilson’s true crime, which was this: He broke character. He was performing in a comedy, but he adopted a tragic tone. That practically guarantees a bad review.

It’s not that Wilson acted like a horse’s behind. That’s standard operating procedure in Foggy Bottom. It’s that he did it with so little finesse. According to the traditions of Congress it can be a natural advantage to be a horse’s behind, but you’re supposed to emit your credentials behind your opponent’s back, not blow them in his face. Republicans in Congress immediately jumped into damage-control mode, accusing the Democratic majority that forced the rebuke vote of playing politics — shocking! — and suggesting that it’s time, as Rep. Eric Cantor of Virginia so nobly put it, to “get on with the business of the people.”

Perhaps the show’s most intriguing plot twist is the revelation, as the New York Times review puts it, that “House guidelines on the rules of debate say it is impermissible to refer to the president as a liar.”

Perhaps the show’s most intriguing plot twist is the revelation, as the New York Times review puts it, that “House guidelines on the rules of debate say it is impermissible to refer to the president as a liar.”

This disclosure, late in the third act, strains credibility. As a member in good standing of the League of Tough-Guy Arts Observers I’m compelled to report that Wilson’s little outburst of jackassery simply can’t hold a candle to the ones you can find in the classics. One of our better theatrical critics, the historian David S. Reynolds, recounts several instances of supreme congressional jackassery in his book Waking Giant: America in the Age of Jackson, including this sketch of Virginia Senator John Randolph, a hard-drinking goliath who regularly put the screws to President John Quincy Adams and others of his many enemies:

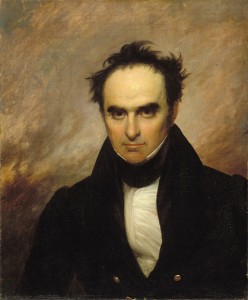

“In a high, squeaky voice, he delivered rambling speeches that sometimes lasted ten hours. Every fifteen minutes or so he paused to swig from a glass of malt liquor or a brandy-and-water concoction; he would go through several quarts in an afternoon. Well lubricated, he lambasted his enemies with abandon. He did not shrink from calling Daniel Webster ‘a vile slanderer’ or Edward Livingston ‘the most contemptible and degraded of beings, whom no man ought to touch, unless with a pair of tongs.’ “

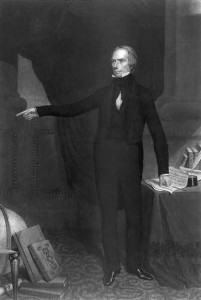

Once, Reynolds reports, Randolph’s abuse was so egregious that Secretary of State Henry Clay challenged him to a duel:

“Clay’s bullet ripped through Randolph’s white flannel coat without wounding him. Randolph’s hit a tree behind Clay. In a second round, Clay again missed Randolph, who raised his gun and fired into the air. The men talked and reconciled. Randolph joked, ‘You owe me a coat, Mr. Clay.’ Clay replied, ‘I am glad the debt is no greater.’ “

Ah, sighs Gus, the Theatre Cat. Now, that’s what I call acting!

Like so many political comedies, The Fall and Rise of the Sharp-Tongued Congressman ends with a mordant twist — a deus ex machina, if you will, setting everything aright and showering blessings on all the characters in the show. Again, from Carl Hulse’s review in the New York Times:

“The episode has become a political bonanza for both parties as Mr. Wilson and his Democratic challenger in the 2010 election, Rob Miller, have each raised over $1 million in the aftermath, and the two parties have benefited as well.”

Now, that’s a happy ending.

The bottom line: A pretty standard medieval morality play, with a veneer of coarse frontier comedy. Vividly drawn characters and some choice moments of burlesque, but a week from now you’ll be hard-pressed to remember any details of the plot.

———————————————

Illustrations, from top, all from Wikimedia Commons:

Daniel “Black Dan” Webster, “vile slanderer” and leading man of the 19th century political stage. Portrait: George Shattuck, 1834. National Portrait Gallery, Washington, D.C.

Henry Clay, fearsome performer in the political theater, always up for a good stage duel. Engraving by John Sartain.

John Randolph of Virginia: Prodigious feats of provocation on the congressional stage. Artist unknown.