By Bob Hicks

We live in an age of miracles so commonplace we rarely think to marvel at them. On a quiet cloudy afternoon Mr. Scatter is standing in his kitchen, balancing on a floor made of oak chopped down and milled and planed almost a century ago, but looking new because it’s protected from scuffs and stains by an invisible, magical plastic coating that freezes entropy in its steps. He is pulling dishes out of a robotic mechanical device called an automatic dishwasher, giving them a swipe or two with a colorfully printed cloth woven somewhere in modern industrial China — China! — and putting them into cupboards that except for their compressed-particle composition aren’t much different from the ones you might see in an 18th century English country house. Scant steps away is the little breakfast nook which, well-wired, is Mr. Scatter’s electronic portal to the virtual world (and what, Mr. Scatter wonders, might a virtual world actually be?).

A few more steps into the dining room is the small stereo system on top of which is cradled a sophisticated, powerful little green computing and storage device called an iPod. Ignoring this more recent communications miracle, he’s fed the system a small bright disc that, powered up, fills the room with sounds that the great bassist and composer Charles Mingus, with an ensemble of other innovative musicians, made in 1959 for an album called Mingus Ah Um. Mr. Scatter relaxes as the burnished rigor of a former revolution curls sharply and gently around him — a revolution that, a half-century on, has become a living, cultured comfort. Exactly the same as it was then, and worlds different.

A few more steps into the dining room is the small stereo system on top of which is cradled a sophisticated, powerful little green computing and storage device called an iPod. Ignoring this more recent communications miracle, he’s fed the system a small bright disc that, powered up, fills the room with sounds that the great bassist and composer Charles Mingus, with an ensemble of other innovative musicians, made in 1959 for an album called Mingus Ah Um. Mr. Scatter relaxes as the burnished rigor of a former revolution curls sharply and gently around him — a revolution that, a half-century on, has become a living, cultured comfort. Exactly the same as it was then, and worlds different.

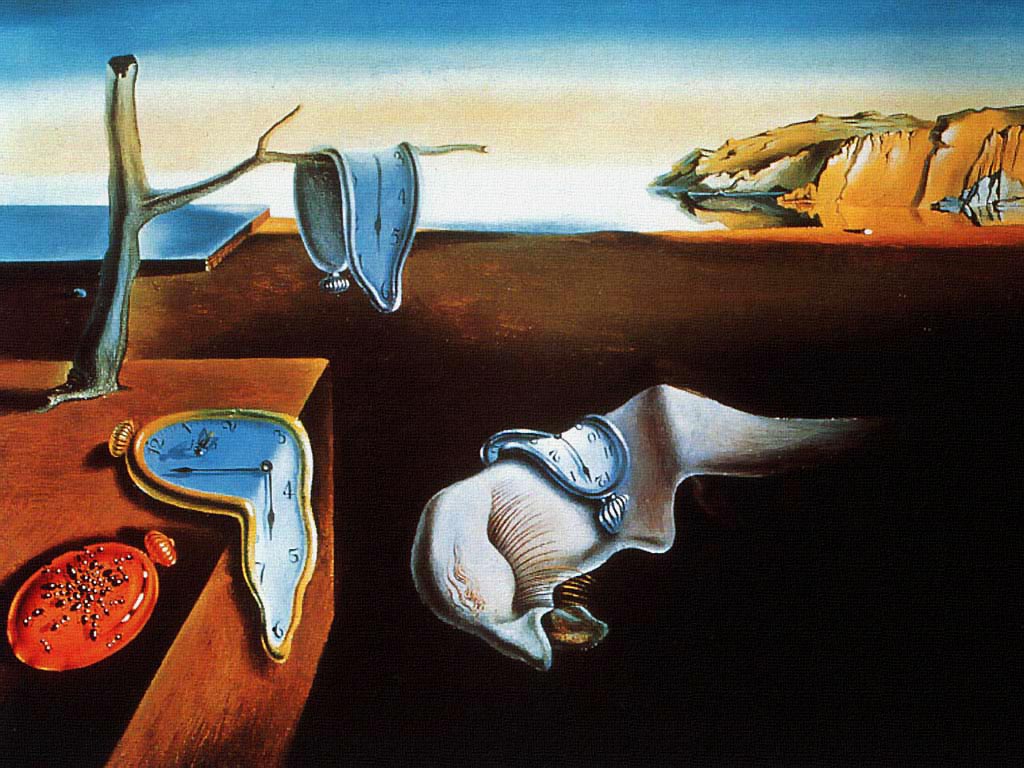

This is our world: Time melts. Salvador Dali is our prophet, and his 1931 melted-clock painting The Persistence of Memory is our holy image.

*

ILLUSTRATIONS:

— Salvador Dali, “The Persistence of Memory,” 1931. Wikimedia Commons

— Charles Mingus, playing in Lower Manhattan on the U.S. bicentennial, July 4, 1976. Source: Tom Marcello Webster, New York, USA/Wikimedia Commons