Robert Fagles, the New York Times reports, has died at home in Princeton, N.J., at 74. Cause of death, prostate cancer. Fagles’ translations of “The Iliad,” “The Odyssey” and “The Aeneid” in another time, a “classical” time, would have made him extremely famous. As it was, they sold millions of copies each and made life a lot easier for college students — who got to read Fagles’ direct, muscular, contemporary translations instead of fighting through Robert Fitzgerald (which I did). Not that there was anything wrong with Fitzgerald: Language and culture move along. Fagles was an update, a potent update. For me, “The Iliad” especially was impenetrable until I found his translation and then for the first time enjoyed it.

Robert Fagles, the New York Times reports, has died at home in Princeton, N.J., at 74. Cause of death, prostate cancer. Fagles’ translations of “The Iliad,” “The Odyssey” and “The Aeneid” in another time, a “classical” time, would have made him extremely famous. As it was, they sold millions of copies each and made life a lot easier for college students — who got to read Fagles’ direct, muscular, contemporary translations instead of fighting through Robert Fitzgerald (which I did). Not that there was anything wrong with Fitzgerald: Language and culture move along. Fagles was an update, a potent update. For me, “The Iliad” especially was impenetrable until I found his translation and then for the first time enjoyed it.

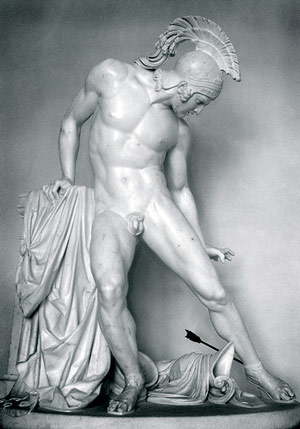

Translation is lovely, tricky business. Did Fagles give us a pristine “Iliad”? Impossible. Homer was already “difficult” for the Greeks in the Golden Age (according Bernard Knox, Fagles’ teacher and friend, in his introduction to Fagles’ “The Iliad”), full of archaic words and modes of expression. I guess I think of it as something vaguely “post-modern,” a pastiche of strange references and allusions, impossible for the non-scholar to understand. But Fagles’ version is what I would like it to be — tough-minded, clever, action-oriented, clear, rather like Odysseus himself. I think Fagles appreciates and shudders at Achilles at the same time, the power and the blood-lust mixed together.

Pick a random passage, Book 21 in this case:

And the god-sprung hero left his spear on the bank,

propped on tamarisks — in he leapt like a frenzied god,

his heart racing with slaughter, only his sword in hand,

whirling in circles, slashing — hideous groans breaking,

fighters stabbed by the blade, water flushed with blood.

Fagles gave us a great, strange Achilles. For that alone, I thank him, and I’m sorry for myself that he won’t be giving us more of the classical world.

Image courtesy of florathexplora on Flickr.

I heard from Art Scatter friend

I heard from Art Scatter friend

A week ago, I sat in on a lecture by Roger Martin,

A week ago, I sat in on a lecture by Roger Martin,