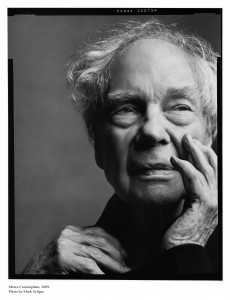

Dance critic and historian Martha Ullman West has spent a lot of time thinking about Merce Cunningham, the great 20th century dancer and choreographer who rethought what dance means by introducing chance as a primary element in the mix. Cunningham, who was born and raised 90 miles from Portland in the small town of Centralia, Wash., died July 26 at age 90. Martha considers, among other things, the effect that the Pacific Northwest had on Cunningham’s art.

__________________________________________________________________

Merce Cunningham died the other day, in his sleep it is said, which means he was still hard at work at the age of 90. Artists do, you know, work in their sleep, as well as their waking hours. There is no rest for the psyche.

Merce Cunningham died the other day, in his sleep it is said, which means he was still hard at work at the age of 90. Artists do, you know, work in their sleep, as well as their waking hours. There is no rest for the psyche.

He died in New York on Sunday, July 26, at his home in Greenwich Village. In his obituary for the New York Times, Alastair Macaulay, who is working on a book on Cunningham, called him “always a creature of New York.”

That’s not untrue, at least from 1939 on, when Cunningham joined Martha Graham‘s company. But it’s only part of the story.

Merce, in fact, was one of ours. So was Robert Joffrey. So are Trisha Brown and Mark Morris, who, thank God, are still around. All are natives of the Pacific Northwest, specifically Washington State.

I believe that Merce’s use of space, his sense of infinite possibility, his connection to nature, his conviction that you can do anything that pleases you on stage as long as it works aesthetically, came from the ethos of this part of the world. You see those elements in the poetry of Gary Snyder, who like Merce and composer John Cage, Merce’s long-term partner in life and art, was influenced by Zen thinking. You see them, certainly, in the work of Trisha Brown.

And, to bring it home to Portland, you see it in the choreography and technique of Mary Oslund, who studied with Cunningham and several members of his company, including the late Viola Farber. Oslund remembers being at dinner with Merce when White Bird presented the company (which, God love them, they did twice, in 2001 and 2004). Merce talked with her about Farber, Mary says, in his “diminutive and humble way.”

“He gave us a lot of permission,” Susan Banyas told dance maker Gregg Bielemeier when she heard the news of Merce’s death.

Continue reading Remembering Merce in his element: the vast Northwest