Sickness is not only in body, but in that part used to be called: soul.

Dr. Vigil, in Malcolm Lowry’s Under the Volcano

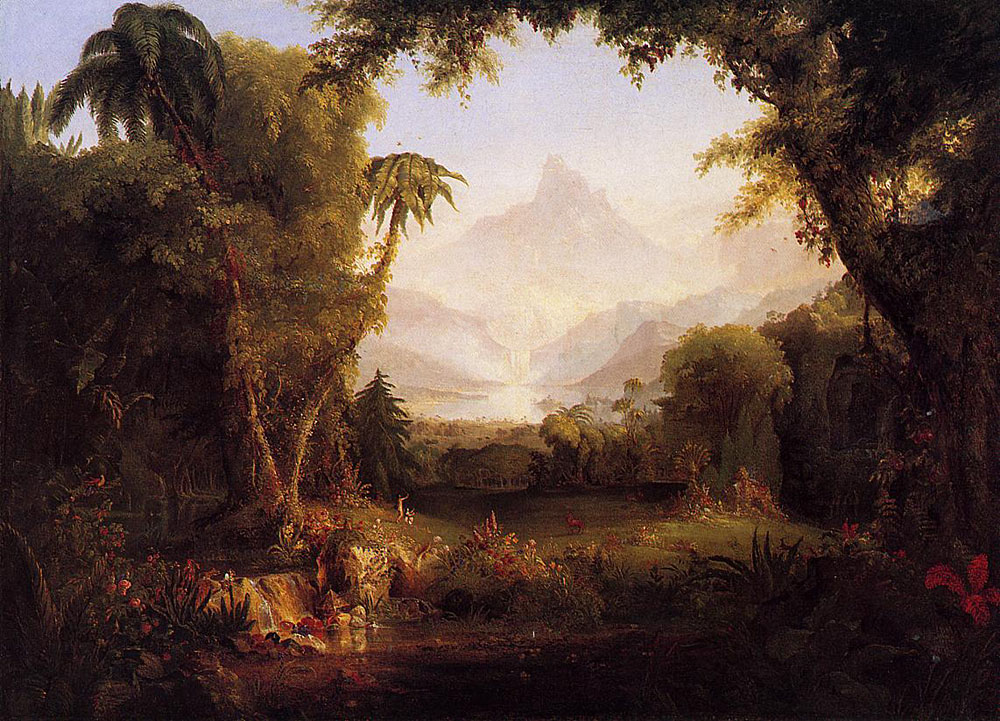

Portlanders have a garden state of mind. Perhaps even a garden state of “what used to be call: soul.†Forest Park meanders through the city. There are the Japanese and Chinese Gardens and all the micro gardens within their perimeters. In one the “enclosing landscape,†as Edith Wharton put it, is forest, except for a panoramic vista of the city; in the other it is high-rise buildings. There is the highly-ordered Rose Garden and, within its confines, the test gardens that supplied the metaphor for Katherine Dunn’s novel Geek Love. There are community and backyard gardens, porch pots all down the block, and desk overhangs in every office. Yes, our garden varietals are many, to include the world’s smallest, Mill Ends Park, all 452 square inches of it, located at SW Naito Parkway and SW Taylor Street.

But with all the gardens and the countless hours gardening per capita, do we live in a “gardenless age†for lack of really “seeing†the gardens in our midst? Robert Pogue Harrison believes so, and I’m always inclined to suspend judgment and follow the course he charts through art, literature, philosophy, psychology and anthropology – you name it – to the clearing he finds in the woods. I’ve kicked around a bit in his new book, Gardens: An Essay on the Human Condition, but barely have disturbed its topsoil. I’ve spent more time with his earlier books, Forests: The Shadow of Civilization (1992) and The Dominion of the Dead (2003), both remarkable for elegant prose and suggestive argument that draw you back for second and third looks. Harrison takes a ruling image – forests, burials, gardens – and explores how they function in human life and institutions, how they filter through the mind as image and metaphor. What he says about gardens, that they “are never either merely literal or figurative but always both one and the other,†captures his working method in all three books. In Forests, for example, it is the realm of trees that provides the meeting ground of human history and nature, and it too defines “the edge of Western civilization, in the literal as well as imaginative domains.â€

But Gardens is not a primer on “literal” gardens or gardening. Harrison is not a gardener, and I’m not reading his book as one. My husbandry extends to mowing lawn, harvesting dog and cat leavings from the yard, and tending – contemplating – a dead bonsai tree that owns a corner of the porch.

Continue reading Robert Pogue Harrison: How does your garden grow?

At the conclusion of Bete Perdue,

At the conclusion of Bete Perdue,

We are more than two months into Art Scatter. Sixty generations of fruit flies have come and gone. One bad knee was replaced by a superior robotic product. We’ve mustered 55 total posts. Our most popular ones have dealt with the Sherwood middle-school theater controversy, Ornette Coleman, graphic non-fiction books, the firing of Deborah Jowitt and getting old. (At least according to our powerful online analysis tool, which is inconsistent enough to make us wonder about its overall accuracy, powerful or not.) So, yes, we think we’re doing our fair share of broadband scattering. It’s fun!

We are more than two months into Art Scatter. Sixty generations of fruit flies have come and gone. One bad knee was replaced by a superior robotic product. We’ve mustered 55 total posts. Our most popular ones have dealt with the Sherwood middle-school theater controversy, Ornette Coleman, graphic non-fiction books, the firing of Deborah Jowitt and getting old. (At least according to our powerful online analysis tool, which is inconsistent enough to make us wonder about its overall accuracy, powerful or not.) So, yes, we think we’re doing our fair share of broadband scattering. It’s fun!