Sickness is not only in body, but in that part used to be called: soul.

Dr. Vigil, in Malcolm Lowry’s Under the Volcano

Portlanders have a garden state of mind. Perhaps even a garden state of “what used to be call: soul.†Forest Park meanders through the city. There are the Japanese and Chinese Gardens and all the micro gardens within their perimeters. In one the “enclosing landscape,†as Edith Wharton put it, is forest, except for a panoramic vista of the city; in the other it is high-rise buildings. There is the highly-ordered Rose Garden and, within its confines, the test gardens that supplied the metaphor for Katherine Dunn’s novel Geek Love. There are community and backyard gardens, porch pots all down the block, and desk overhangs in every office. Yes, our garden varietals are many, to include the world’s smallest, Mill Ends Park, all 452 square inches of it, located at SW Naito Parkway and SW Taylor Street.

But with all the gardens and the countless hours gardening per capita, do we live in a “gardenless age†for lack of really “seeing†the gardens in our midst? Robert Pogue Harrison believes so, and I’m always inclined to suspend judgment and follow the course he charts through art, literature, philosophy, psychology and anthropology – you name it – to the clearing he finds in the woods. I’ve kicked around a bit in his new book, Gardens: An Essay on the Human Condition, but barely have disturbed its topsoil. I’ve spent more time with his earlier books, Forests: The Shadow of Civilization (1992) and The Dominion of the Dead (2003), both remarkable for elegant prose and suggestive argument that draw you back for second and third looks. Harrison takes a ruling image – forests, burials, gardens – and explores how they function in human life and institutions, how they filter through the mind as image and metaphor. What he says about gardens, that they “are never either merely literal or figurative but always both one and the other,†captures his working method in all three books. In Forests, for example, it is the realm of trees that provides the meeting ground of human history and nature, and it too defines “the edge of Western civilization, in the literal as well as imaginative domains.â€

But Gardens is not a primer on “literal” gardens or gardening. Harrison is not a gardener, and I’m not reading his book as one. My husbandry extends to mowing lawn, harvesting dog and cat leavings from the yard, and tending – contemplating – a dead bonsai tree that owns a corner of the porch.

In fact, Harrison discusses gardens only to establish what they symbolically represent, the relation between humankind and nature. Gardens can be food-producing or ornamental, haven or sanctuary, but they also represent “work,†a concept he borrows from Hannah Arendt’s The Human Condition, meaning the building of the worlds that make us historical creatures. Specifically, “cultivation†is the concept he tweaks from various texts, including Dante, Boccaccio, Edith Wharton, Italo Calvino, the Czech writer Karel Capek, and the Greek philosopher Epicurus.

Here’s how he explains the garden tended by Epicurus and his disciples:

Yet it was not for the sake of fruits and vegetables alone that they assiduously cultivated the soil. Their gardening activity was also a form of education in the ways of nature: its cycles of growth and decay, its general equanimity, its balanced interplay of earth, water, air, and sunlight. Here, in the convergence of vital forces in the garden’s microcosm, the cosmos manifested its greater harmonies; here the human soul rediscovered its essential connection to matter; here living things showed how fruitfully they respond to a gardener’s solicitous care and supervision. Yet the most important pedagogical lesson that the Epicurean garden imparted to those who tended it was that life – in all its forms – is intrinsically mortal and that the human soul shares the fate of whatever grows and perishes on and in the earth. Thus the garden reinforced the fundamental Epicurean belief that the human soul is as amenable to moral, spiritual, and intellectual cultivation as the garden is to organic cultivation.

“Cultivation,†“care,†and “soul†– terms Harrison employs to move from the literal gardens to figurative “cultivation†of the human “soul†or spirit, as old-fashioned as that might sound. “The soul is not like soil, in other words, it is itself a kind of soil – call it an organic-spiritual substance – in which the teacher, like the gardener, can sow his most valuable seeds and nurture their growth to full maturity.†Harrison explores the notion of cultivation in education, therapeutic gardening, marriage, as well as social and political relations as an aspect of “civil humanism.†In particular, he says that “we must always remember that nature has its own order and that human gardens do not, as one hears so often, bring order to nature; rather, they give order to our relation to nature.â€

Our relation to nature, of course, is attenuated, which, in part, accounts for Harrison’s belief that we live in a “gardenless age†and no longer “see†the soul’s connection to earth, the “organic substrate†of our animal nature. I can’t say if this is a leap, or if I’ve missed more of the connecting tissue of argument, but he tries many terms – discrete and discontinuous, hypertension, restlessness, pointlessness, yearning – before settling on “aimless drivenness†as the most apt characterization of the active and destructive urges prevalent in our age, especially in our relation to nature.

Our relation to nature, of course, is attenuated, which, in part, accounts for Harrison’s belief that we live in a “gardenless age†and no longer “see†the soul’s connection to earth, the “organic substrate†of our animal nature. I can’t say if this is a leap, or if I’ve missed more of the connecting tissue of argument, but he tries many terms – discrete and discontinuous, hypertension, restlessness, pointlessness, yearning – before settling on “aimless drivenness†as the most apt characterization of the active and destructive urges prevalent in our age, especially in our relation to nature.

I recognize the symptoms he describes and agree with much of what he says about the compulsions in capitalism and consumer culture, but I don’t know that “cultivation,†literal and figurative and rightly understood, is a fulcrum for change. I don’t see a national dialogue on cultivation forwarding the debate on what to do about climate change. Although, since the Reverends Al Sharpton and Pat Robertson have now joined hands on the issue, anything would seem possible.

Perhaps what Harrison terms our “stupor†in the face of these issues, accounts for the stridency and hectoring that pops up in parts of Gardens. I say that because I hate to think Gardens is a fatalist’s jeremiad, a lamentation for something that is lost to us, beyond any desire or ability to redeem. As I think about the three books, I’m inclined to think he’s tried to bring his broad learning to bear in support of alarms sounded by scientists and environmentalists, but with increasing frustration. The last chapter of Forests, “The Ecology of Finitude,†has an urgency, but as an appeal, with some sense of hope.

Instead of urgency, Gardens conveys haste, impatience. His books, all published by the University of Chicago Press, are elegant and balanced, a pleasure to hold and read. But in Gardens I found several typos, and the notes to one chapter revise what is said in the text based on information discovered after he had written the chapter. Why not revise the chapter? And there’s an unconvincing discussion of gardens in the Qur’an that seems more an awkward attempt at rapprochement between Christianity and Islam than it does a deepening or expansion of the main theme of the book. And I don’t know that zeroing in on college students, and asserting they are oblivious of the visible world, “except peripherally and crudely,†is the best example of our age’s inability or unwillingness to “see.†(He admits it might sound “curmudgeonly.†It does.)

But none of this dampened the excitement and fascination I felt in my first reading. And there’s much in Gardens I haven’t touched on. Harrison sends you running to authors old and new, and gives you eyes to see things from a different perspective. His chapters are like beautiful rooms full of neat stuff, and you’re free to rattle around in them, lost in thought. (The notes are like cabinets of curios in the corner of each room.)

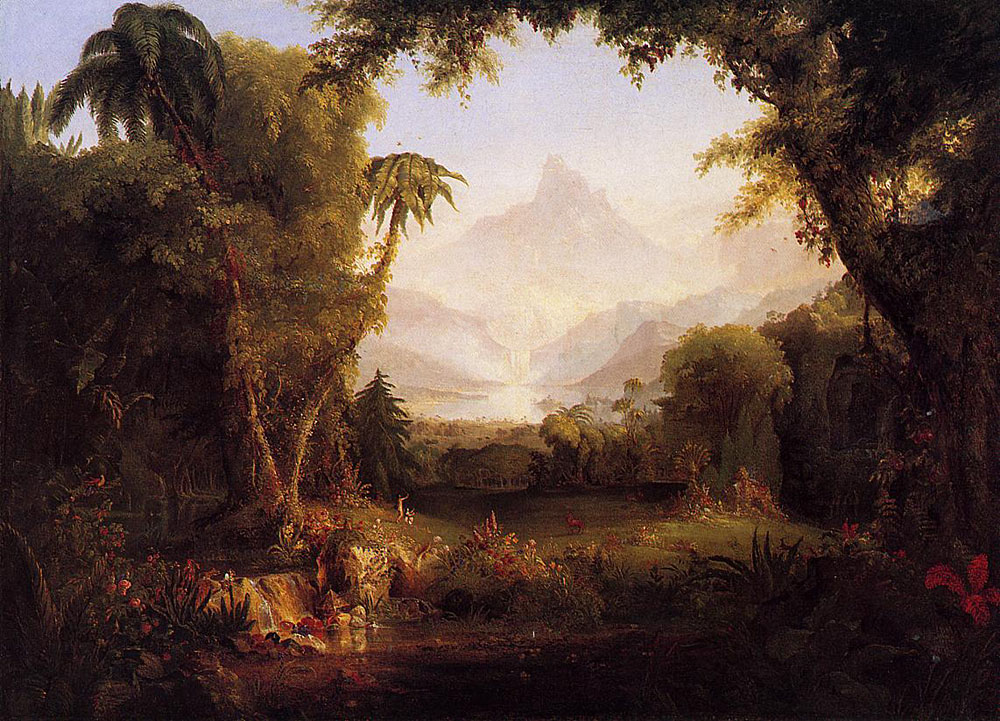

I’m still spinning out one idea Harrison traces in Lionel Trilling on Modernists, A. Barlett Giamatti on Renaissance epics, and Malcolm Lowry in Under the Volcano, and that is, the idea that Adam hated the sterility and boredom of the Garden of Eden, and God, as punishment, left the first couple there. Harrison’s alternate version is that Eve hated the place and engineered the expulsion in order place humanity on the path to maturity and fulfillment through work and cultivation. In any event, “we were handed over to our self-responsibility,†and “left in a garden we were called on to keep.â€

And, Harrison reminds us, “we’re still there.â€