High above the windy hollow of the Columbia River Gorge, Sitting Bull and Geronimo and Gen. George Armstrong Custer seem right at home.

High above the windy hollow of the Columbia River Gorge, Sitting Bull and Geronimo and Gen. George Armstrong Custer seem right at home.

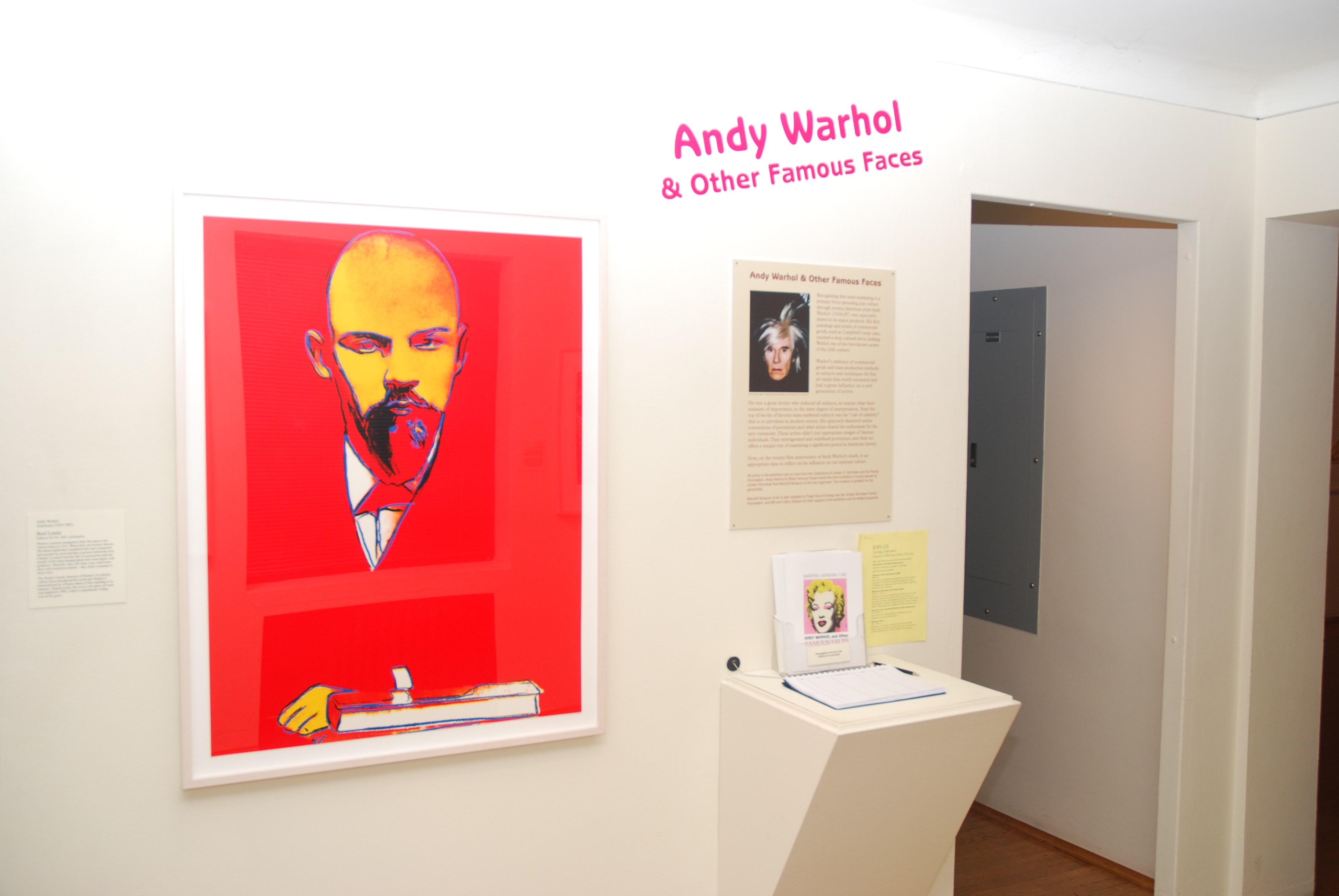

And Andy Warhol? Surprisingly, him, too.

Warhol, the epitome of a certain sort of New York sophistication — a self-created phenomenon of the 20th century, pointing the way to the 21st — is the focus of a new show in the upper galleries of the Maryhill Museum of Art, “Andy Warhol and Other Famous Faces,” assembled from the contemporary print collections of Jordan D. Schnitzer and his Family Foundation.

The exhibit, with images mostly by Warhol plus a sprinkling of supporting pieces by the likes of Robert Rauschenberg, Red Grooms, Chuck Close, Jasper Johns and Jeff Koons, proves once again what has become a mass-culture commonplace: In a world of celebrity-soaked informational sameness, we are all from Manhattan, all from Iowa, all from the sparse deserts of the West. Red state or blue, right wing or left, Elvis and Marilyn and Campbell’s Tomato Soup have brought us together and made us alike — or at least, given us the same pop-cultural preoccupations.

Maryhill, one of the unlikeliest of American art museums, sits in a concrete castle on a high bluff on the Washington side of the Columbia River, about 100 miles east of Portland and well on the way to desert country: It’s practice territory for the Middle of Nowhere. The fortress was built as his residence by the visionary road engineer and agricultural utopian Sam Hill. (His Stonehenge replica, a World Wat I memorial, is nearby, and the next time you head for Vancouver, British Columbia, you should stop on the border at Peace Arch Park to take in another of his monuments, the International Peace Arch, which sits with one foot in Blaine, Washington, and the other in Surrey on the Canadian side. Both monuments are as clean-lined and populist as any of Warhol’s works, and a good deal more interactive.)

Hill’s mansion was transformed into a museum by three of his high-powered women friends, including Marie, Queen of Romania, who was related to the royal houses of both England and Russia. As a result its collections are heavy in memorabilia of the good queen’s life (including some furniture she designed), plus objects related to another benefactress, the great dancer Loie Fuller; a goodly amount of Rodin; a good sampling of Native American art; many fine Russian Orthodox icons; quirky attractions such as the French high-fashion stage scenes of Theatre de la Mode (even Jean Cocteau took part in this immediately post-World War II artistic attempt to give French haute couture a sorely needed economic kick-start); and an amusing, sometimes amazing sampling of international chess sets.

Hill’s mansion was transformed into a museum by three of his high-powered women friends, including Marie, Queen of Romania, who was related to the royal houses of both England and Russia. As a result its collections are heavy in memorabilia of the good queen’s life (including some furniture she designed), plus objects related to another benefactress, the great dancer Loie Fuller; a goodly amount of Rodin; a good sampling of Native American art; many fine Russian Orthodox icons; quirky attractions such as the French high-fashion stage scenes of Theatre de la Mode (even Jean Cocteau took part in this immediately post-World War II artistic attempt to give French haute couture a sorely needed economic kick-start); and an amusing, sometimes amazing sampling of international chess sets.

But the museum’s permanent fine-art holdings are largely romantic landscape, plus Victorian and American realist paintings. As a result, it relies largely on temporary shows for things a little closer to modern times.