I’m just trying to do this jig-saw puzzle

Before it rains anymore

– M. Jagger / K. Richards “Jigsaw Puzzleâ€

Ours is a family of re-puzzlers. Last holiday our sons, both in their mid-twenties, spent two days working through our old puzzles, beginning with the extra large-piece “Masters of the Universe,†a “battle royal†featuring He-Man and two dozen other trademarked Mattel heroes of the day (circa 1983). From there they moved to “G.I. Joe Battles Cobra Command,†four puzzles that, when completed, can be interlocked to form a large mural depicting all-out war on land and sea and in the air. These boys have always been deliberate, methodical re-puzzlers. As youngsters they would build them, tear them down and build again. As adults they are also deliberate about seeming disengaged; they are handling memories, after all, not puzzle pieces.

My wife and I joined them on the adult puzzles, some we’ve had since the late 1960s, when we were first married and a bottle of wine and a good puzzle were an evening’s entertainment: “Fisherman’s Wharf,†in Monterey, California, the way it looked when we lived there; “Five-Clawed Dragon,†a detail from an embroidered Chinese Imperial robe; and “St. George and the Dragon,†a photograph of a statuette owned by a Bavarian duke who lived during the time of Shakespeare.

Oh, we’ve had other, one-time puzzles, more than I’d want to count, but these are the ones we’ve kept and re-puzzled time and again. Life is like a jigsaw puzzle, I’ve thought. Not like a box of chocolates. The puzzle worked over and completed, and then un-puzzled and tossed back into its box, is the seven ages of man – the first youthful stammering returning to reclaim incoherence from the modest settled principles an adult pieces together once, maybe twice, in a life.

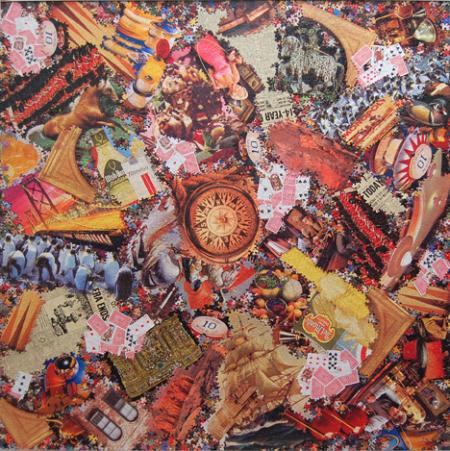

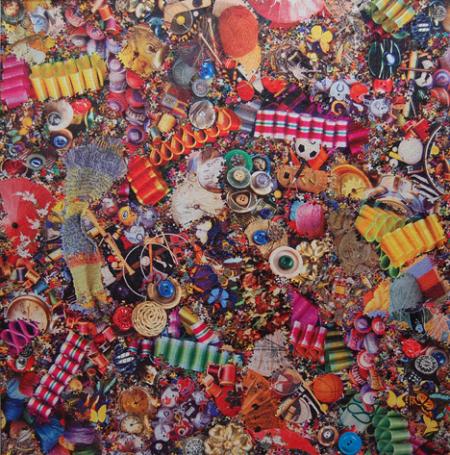

So I was curious to see Al Souza’s sculptural jigsaw puzzle collages showing at Elizabeth Leach Gallery this month. He uses commercial puzzles gathered from thrift stores and on E-bay, and some that acquaintances around the country find and assemble for him. He layers and juxtaposes parts of the puzzles in large scale works such as “Italian Dressing†(72†X 72â€, above), creating an explosion of slick images and bright colors that are the hallmark of commercial puzzles. Animals, clocks, landscapes, famous paintings and buildings, loopy holiday ribbon candy, toys and sports memorabilia – jumbled together in odd, surprising ways.

Abstract, random and yet seamless from a distance, the images are more discrete close up, but with interesting visual effects. You follow the lines of individual pieces that fit together for one picture, one section of a puzzle. The broken edge where Souza has removed a section blends with a different puzzle in the layer below – but not quite. It’s a complete puzzle, and yet not. You think, this is not my jigsaw puzzle! A jigsaw puzzle represents a fairly rigid ideal in life. A two-dimensional space complete onto itself. The tessellation or tiling effect created by the interlocking pieces ties this small, square or round world together with no gaps or overlaps. Moreover, a puzzle’s final bit of relevance is the moment when the last piece in pushed into place. For true puzzlers it has no afterlife as finished picture. When done it is torn up and readied to begin again. At any rate, that’s conventional puzzler’s wisdom.

Which is why Souza’s work seems so counterintuitive, a mocking high brow celebration of the very low brow art of puzzle conversion, where finished puzzles are glued to a backing board, framed, and hung on the wall as art. Thus, art’s kitschy cousin becomes real art, but as fragments, and not just fragments, but fragments layered on other fragments in violation of two-dimensional wholeness.

In fact, Souza’s practice undermines the puzzler’s clean existential routine. His art is so purposeful! All those hours Souza’s collaborators spend finding the puzzles and piecing them together, and then sending them to Souza, who willy-nilly breaks them up, re-forms them fragment to fragment, layer upon layer, and glues and frames them for permanent display in the museum.

Turn and turn about, as Samuel Beckett said of equilibrium, neatly managed. But there’s another interesting twist. I noticed that Souza’s “Italian Dressing†includes two chunks of “Saint George and the Dragon,†my favorite puzzle.

I admire Souza’s deft handling of this post post-art thing, the way I admire the idea Robert Rauschenberg had the day he erased a de Kooning drawing and showed the result as his own work. Let’s see. The museum sells the rights to the image to a puzzle-maker who reproduces the image and mass-markets it as a puzzle. Souza repackages the image and sells it, like it’s a mustache on a Mona Lisa smile, to another wing of the museum. At the time we bought “Saint George and the Dragon†in 1969, the statuette it is a photograph of was held by the Residenz Museum in Munich, Germany, and I imagine it’s still there, waiting for “Italian Dressing.†(And the puzzle company is waiting to jigsaw “Italian Dressing.â€)

But I had another thought, too. “Saint George and the Dragon†is a stunning image. It’s the most difficult puzzle I’ve ever worked on. Saint George in armor on his horse is poised over the prostrate body of a defeated dragon, ready to plunge his saber into the dragon’s heart. The three are held up by a base festooned with a coat of arms and lions and garlands and well-appointed female figures, the whole concealing a drawer that is rumored to hold a reliquary of Saint George, perhaps a charred bone or blood-stained ribbon? The thematic elements are repeated and balanced, intricately fashioned from fine materials: gold, silver, chalcedony, green and white enamel, and some 2,291 diamonds, 406 rubies, and 209 pearls.

It takes a long time to piece this thing together. The diamonds and pearls look like all the other diamonds and pearls. Down to the last dozen pieces it is still not obvious where they fit or if they fit at all. Like life, I’d say. And it seems to me a desecration of it not to crumple the finished thing and dump it back in the box.

At the Gallery I stared at the two parts of “Saint George and the Dragon” glued to the face of Souza’s collage and experienced one of those moments that open a hole in the world. I thought of our sons piecing together “Masters of the Universe†time and again, and, in doing it, intuitively understanding their portion of said universe, and their position in it. I thought of the times my wife and I slouched across the table, hip to hip, turning pieces here and there, the puzzle-within-the-puzzle ever unfinished. I thought of all the puzzles in their boxes, all unfinished, or, if finished, un-puzzled once more. And I thought of Samuel Beckett. I thought, “What if Godot shows up?â€

Souza’s art, I think, is an art that I do not like.

I have an old slip of paper with a Beckett quote printed on it, talking to Georges Duthuit about the fate of the artist, resigned to “the expression that there is nothing to express, nothing with which to express, nothing from which to express, no desire to express, together with the obligation to express.†I’ll save you the trouble of looking up the last words of Beckett’s “The Unnameableâ€: “You must go on, I can’t go on, I’ll go on.â€

Crumpling the finished puzzle and throwing it in the box is my act of faith in the wisdom of that thought.

I’m a re-puzzler and I approve this message.