By Bob Hicks

The fun thing about art is that it always seems to come with a story. Not that the stories are more important than the art — at least, not usually — but they do have a way of getting a potentially esoteric subject down to the nitty gritty.

Martha Ullman West, whose tale about the painter Titian and the man-about-Europe Pietro Aretino provided the pith for our previous posting, took a break from the thickets of her book manuscript to send along another quick story, this one about the American painter Alfred Maurer, whose 1932 Cubist version of George Washington was included in a piece I wrote in this morning’s Oregonian about images of faces in the permanent collection of the Portland Art Museum. The story was a sidebar to my cover story about Titian’s La Bella, which is on temporary display at the museum. Martha’s father, to complete the setup, was the New York painter Allen Ullman, and her grandfather was the artist Eugene Ullman, so inside stories about artists flowed like wine in her childhood home.

Martha Ullman West, whose tale about the painter Titian and the man-about-Europe Pietro Aretino provided the pith for our previous posting, took a break from the thickets of her book manuscript to send along another quick story, this one about the American painter Alfred Maurer, whose 1932 Cubist version of George Washington was included in a piece I wrote in this morning’s Oregonian about images of faces in the permanent collection of the Portland Art Museum. The story was a sidebar to my cover story about Titian’s La Bella, which is on temporary display at the museum. Martha’s father, to complete the setup, was the New York painter Allen Ullman, and her grandfather was the artist Eugene Ullman, so inside stories about artists flowed like wine in her childhood home.

Martha writes:

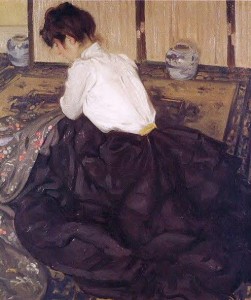

“I was thrilled to see the thumbnail cut of Alfred Maurer’s George Washington. Alfy, as my grandparents called him, was the son of a lithographer who did meticulous pictures of the American West, showing every feather on an arrow, every curl on a buffalo hide. He wanted his son to make similar art, and evidently Alfy could draw like nobody’s business. But he got no recognition for such skills, never mind sales, and he lived in Paris in the period between the wars on the proceeds of the sale of American postage stamps, which his father generously sent him. I checked the Wikipedia article for info about Alfy, and found it illustrated by an Impressionist-tinged painting I know well, because the model is wearing a fantastic black skirt that actually belonged to my grandmother. Anyway, once he broke free from papa’s influence and began doing the modern/cubist stuff as shown in George Washington he began to get some recognition. His father died when Alfy was over sixty, I think, and with no tyrant to rebel against, Alfy evidently couldn’t go on, so he hanged himself.”

At right is Alfred Maurer’s painting of Martha’s grandmother’s skirt, a 1901 oil on cardboard titled The Arrangement. It’s from the days when Alfy’s father was proud of his son’s work. That would change, drastically. The Father of Our Country wasn’t the only father whose attitudes and actions agitated Alfred Maurer’s imagination.

At right is Alfred Maurer’s painting of Martha’s grandmother’s skirt, a 1901 oil on cardboard titled The Arrangement. It’s from the days when Alfy’s father was proud of his son’s work. That would change, drastically. The Father of Our Country wasn’t the only father whose attitudes and actions agitated Alfred Maurer’s imagination.

The Wikipedia article that Martha mentions also includes this extended quotation from artist Jerome Myers‘ 1940 book Artist in Manhattan:

“Alfred Maurer, whom I knew casually, had a pleasant personality. After his early talent had brought him a prize at the Carnegie Institute, he went to Paris, where he stayed for years. Through mutual friends, I had often heard of him, and when subsequently I came to Paris, we spent some time together.

There was no doubt that he was happy in his Parisian atmosphere. Like many other young Americans there, he was attracted by the life of the boulevards, the cares, the daily affinity with brother artists with whom he was then studying the problem of color. I found him experimenting with his close friend Eugene Ullman [editor’s note: This is Martha’s grandfather], who had adopted Paris with the same enthusiasm. In his appearance, Alfred Maurer was romantic, gay and debonaire, the typical artist seemingly beyond all drab necessity.

His father, Louis Maurer, was an old-time artist, who had worked on the Currier & Ives lithographs. When I met him at an exhibition of the Independents at the Grand Central Palace, he was a quiet-mannered man, whom I took to be about seventy-five years old. Later I learned that he was then already ninety-five. He told me how surprised he was at the value and vogue attained by the Currier & Ives lithographs, which in his time had been merely ordinary subjects for simple homes, like the vast number of engravings of that period. Speaking of his son, Alfred, he evidently could not sympathize with — or, as he said, understand — the ultra-violets and ultra-blues of that phase of Alfred’s work. He seemed so proud of what his son had done, but so grieved at what he was then doing.

For some reason, Alfred was subsequently forced to return to New York, leaving behind in Paris his beloved boulevards and the friends of his heart. The idea and the style of his work seemed to change; he turned to the painting of elongated women, after the pattern of Modigliani. Then Louis Maurer, seemingly outraged by his son’s work, did an extraordinary thing. He gave an exhibition of his own paintings at the age of one hundred years, a record for all time. Between this unique rejuvenescence of his remarkable father, with the implied reproof against his own art, and the suffering due to ill health, the pit yawned and the unhappy Alfred Maurer left the scene of his sorrows a suicide, his gallant heart broken.”

That’s a story. Looking on Wikipedia for Louis Maurer, Alfred’s father, I discovered the print below, which perfectly illustrates Martha’s description of his Western paintings as revealing “every feather on an arrow, every curl on a buffalo hide.” It’s called The Great Royal Buffalo Hunt, from 1895:

- Alfred Maurer, “George Washington,” oil on composition board, 1932. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Jan de Graaff. 53.24. Portland Art Museum.

- Alfred Maurer, “The Arrangement,” oil on panel, 1901. Wikimedian Commons.

- Louis Maurer, “The Great Royal Buffalo Hunt,” color print, 1895. Wikimedia Commons.