By Bob Hicks

Lanky and improbably lean-headed, with a cliffside of forehead pierced by a widow’s peak of bristling orange hair, Dan Donohue looks a little like the late-night television host Conan O’Brien — or maybe an O’Brien sired by Loki, the god of mischief.

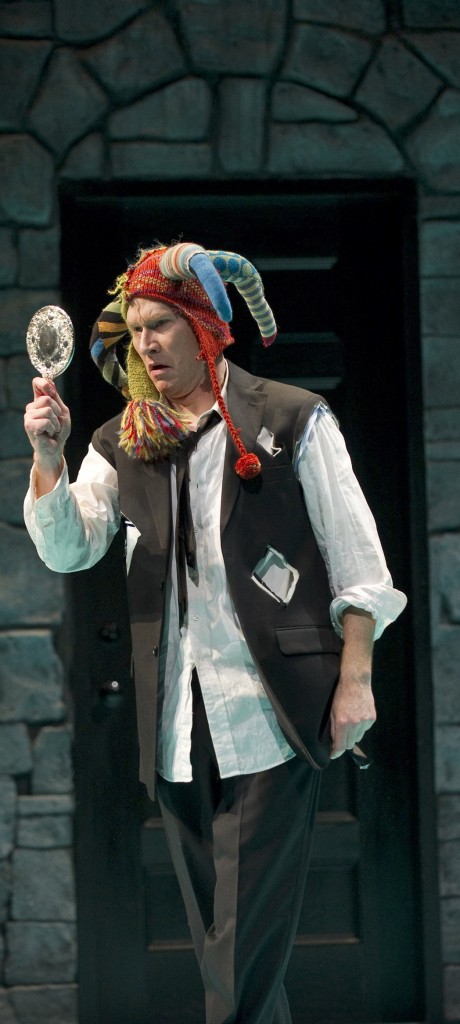

As Hamlet in the Oregon Shakespeare Festival‘s current production of the Danish play, Donohue wears his jester’s cap naturally, less like a disguise than a key accoutrement to an essential part of his makeup: Hamlet the Fool.

As Hamlet in the Oregon Shakespeare Festival‘s current production of the Danish play, Donohue wears his jester’s cap naturally, less like a disguise than a key accoutrement to an essential part of his makeup: Hamlet the Fool.

We’ve come a long way from Olivier, the quintessence of the romantically doomed heroic prince. Olivier once talked about the advantages of being not quite short and not quite tall: at about five-foot-eleven, he could shift the sense of his body big or small. Donohue is similarly poised between the comic and the dramatic, at ease in either direction and often, onstage, using elements of one to feed the other: He defies type. In the impenetrable yet irresistible question mark that is Hamlet, it’s an excellent place to begin.

There is no such thing as a definitive Hamlet. A lot of good actors have stumbled in the prince’s shoes, perhaps daunted by the familiarity of the language and previous performances, perhaps unwilling or unable to choose a Hamlet rather than reach for the Hamlet. Donohue is ready for the role. Consciously or subconsciously, he’s been preparing for Hamlet for a long time. On the Ashland stages he’s played Iago, Caliban, Mercutio, Prince Hal — all excellent prep for Hamlet. And anyone who recalls his Dvornichek in Tom Stoppard’s Coward-like farce Rough Crossing, or who sees his brief turn as the waiter in this season’s sparkling revival of the musical She Loves Me, understands his brilliance at deadpan comedy. He knows precisely who he wants his Hamlet to be, and that, combined with his potent craftsmanship and willingness at key moments to simply drop off the cliff and into the abyss, makes this one of the extremely few truly satisfying Hamlets I’ve seen. It’s a wonderful performance, and you really ought to see it.

I spent a couple of hours with Kenneth Branagh when his 1996 movie version of the play was released, talking with him about acting, his career, and his approach as actor and director to Hamlet. (His version has always struck me as intensely political, the portrait of a prince trying to bring back balance to a disastrously listing ship of state. It’s also one of the few versions to really make hay with the looming offstage presence of Fortinbras, waiting to strike.) Branagh followed, among several others, Olivier, Richard Burton and Nicol Williamson in creating film versions of the role, and he didn’t see one version as replacing another, only as the necessary following of night from day. “Every generation needs its own Hamlet,” he said.

It’s too much of a stretch to say that Donohue’s prince speaks for a generation, but he’s very much shaped from a generation. This is a Hamlet for our time, a prince muddled and bittered in the sterile solace of irony. Donohue stands a little to the side, dripping sarcasms over a general state of personal and institutional corruption that feels out of his control. He exudes a touch of generational suspicion that everything worth doing has already been done and the only rational or honorable course is to tear things down so you can start over again. It’s a sense of futility: Folks, we’re in over our heads, and it ain’t our fault. It’s here where Donohue seems to feed off the inspiration of Shakespeare’s fools, shrewd men who use humor and mock confrontation to speak otherwise unspeakable truths — or at least, unspeakable in the halls of power. We’ve had our own versions, from Lenny Bruce and Richard Pryor to Hugh Laurie and Stephen Colbert.

Donohue’s cloak of cynicism draws out the coarse comedy hidden in the play, providing him multiple opportunities to shock the characters around him with behavior just outside the accepted norms. He cuts to the quick. Snip-snip. The leg of his expensive suit pants shears at the seam. Snip-snip. He decapitates Polonius’s necktie and hands it to him for a bookmark. Perhaps taking his cue from Howie Seago’s ghost, who performs in sign language, Donohue brings an eloquent, dancerly movement to his performance, a physical expressionism that whispers of hyped-up noh. At key moments his mask of cynicism slips and the struggling idealist emerges, carrying an immense sadness and curdling rage as he pushes to the surface. The world has turned, this Hamlet realizes, and there is no good way to turn it back.

Donohue’s approach to the language is both fresh and knowing, steeped in tradition without being humbled by it. Too many Hamlets gear up for the big speeches, taking a big metaphorical breath and then leaping into the Famous Words. Donohue enters by the back door, slipping into the speeches almost before you’ve noticed and, once he’s inside, toying with them. It feels naturalistic but isn’t really at all. The speeches seem at once extemporaneous and ritualistic: He toys with the well-worn phrases, placing them in metaphoric quotation marks, emphasizing them by de-emphasizing them, treating them with ironic affection, and all in all creating a whole new rhythm. He’s not alone in this stylized naturalism: the superb Richard Elmore, for instance, delivers Polonius’s famous “Neither a borrower nor a lender be” speech in a colloquial, offhand, slightly blowhard but also practical way.

Any Hamlet exists within a context, and director Bill Rauch has shaped a production worthy of its core. It, too, knows what it wants to be, and despite its bells and whistles its calling card is its freshness and rethinking of the language so that it flows, as much as possible, as if it were being spoken for the first time. Jeffrey King’s Claudius, Bill Geisslinger’s gravedigger, Armando Duran’s Horatio, David DeSantos’ Laertes — all are quick and deceptively casual on their deliveries, thinking out the rhythms and emphases as if they were new. And company newcomer Susannah Flood is bright and gutsy, even funny, in the ordinarily thankless role of Ophelia: for once, she makes you truly regret that Hamlet drives his girlfriend around the bend. Stylistically, the production is a little too contemporary for some: “It’s too noisy!” one knowledgeable and perceptive onlooker complained, speaking not just of the rap-style play within the play but also of the effects-laden production as a whole. I don’t agree. With a couple of minor exceptions I think Rauch’s decisions are smart and effective, carrying the core of the drama into a contemporary setting and making it feel like a story only just being told.

Of course, it’s not definitive. In the end, Ashland’s Hamlet doesn’t answer the many questions that have plagued and beguiled audiences over the centuries. Did Gertrude help Claudius plan the thing? Did Polonius and Rosencranz and Guildenstern deserve it? Should Hamlet have just ignored the ghost and let the New Order establish itself? Why did he treat Ophelia so unspeakably? Did he have the hots for Mom? Was he mad? (a question, I think, that’s reductive and largely irrelevant, anyway.) There’s always next time, when the questions won’t be answered once again.

*

PHOTO: Dan Donohue as Hamlet is nobody’s — and everybody’s — fool. Photo: David Cooper.