By Bob Hicks

Art Scatter interrupts its regular programming to bring you a message from the future: It’s not your Daddy’s Oregon Shakespeare Festival anymore.

Not entirely, anyway. You remember the “Ashland style.” Elizabethan costumes on the Elizabethan Stage, broad low comedy breaking up flights of earnest declamation, lines delivered clearly and concisely so you understand the purpose if not always the interior fever of the plays. For decades the festival has made a virtue of old-fashioned verity, and if that’s the way you like it — a goodly number of people do — this season’s Henry IV, Part I is for you: an unruly time bomb of a Prince Hal (John Tufts), a broken-down and overpadded blowhard of a Falstaff (David Kelly), a hot and hardy Hotspur (Kevin Kenerly). This is Shakespeare in the festival tradition, solid as a burgher, tried and true.

And suddenly, that makes it feel almost anachronistic.

The festival is changing, reinventing itself in front of our eyes. It’s not a revolution, it’s a profound evolution: Ashland has joined the 21st century. This season’s fruit of reinvention includes American Night: The Ballad of Juan Jose, a smart and often uproarious piece of agitprop by Richard Montoya and Culture Clash; and Throne of Blood, a visually ravishing stage adaptation by the masterful Ping Chong of Akira Kurosawa‘s 1957 film masterpiece, which was itself a radical reimagining of Macbeth.

The festival is changing, reinventing itself in front of our eyes. It’s not a revolution, it’s a profound evolution: Ashland has joined the 21st century. This season’s fruit of reinvention includes American Night: The Ballad of Juan Jose, a smart and often uproarious piece of agitprop by Richard Montoya and Culture Clash; and Throne of Blood, a visually ravishing stage adaptation by the masterful Ping Chong of Akira Kurosawa‘s 1957 film masterpiece, which was itself a radical reimagining of Macbeth.

That’s on top of a Hamlet with hip-hop overtones and an utterly charming She Loves Me, the exemplar so far of artistic director Bill Rauch’s devotion to the stage musical as a legitimate and important branch of the theatrical family tree. Watching this year’s Henry IV, Part I is edifying and at times even exciting, but it isn’t all that different from taking in an Ashland Shakespeare in 1975 or 1995. American Night, Throne of Blood, Hamlet and She Loves Me? It’s a whole new festival, baby.

How did we get here? The festival has been playing around with its own expectations for decades. The late Jerry Turner, in his long artistic tenure following founder Angus Bowmer, nudged the Shakespearean boundaries in a lot of ways, from his abiding interest in Ibsen and O’Neill to his inheritance of the company’s first indoor stage, the Angus Bowmer Theatre, which forever changed the festival’s repertory and ambitions. Henry Woronicz, in his brief artistic leadership, pushed for an American openness, hiring nonwhite artists and broadening the company’s pool of energy and ideas. His successor, Libby Appel, battled the company’s isolationism by engaging it more fully with the outside theater world. The accumulation of these gradual changes has gone viral under the leadership of Bill Rauch, Appel’s successor, who’s been quietly but effectively kicking over the festival’s walls of expectation.

American Night (the first of a projected 37 new plays in American Revolutions, the festival’s ambitious cycle of pieces about United States history) and Throne of Blood represent not just a fresh way of looking at theater but also a willingness to produce shows that not everyone will like. That’s important. A company in a small, isolated town that relies on tourism to build its audiences faces the inevitable temptation of presenting nothing but crowd-pleasers. Ashland has done a good job over the decades of fighting the tendency, but there’s always been a touch of it, and indeed, the likes of this season’s Pride and Prejudice and She Loves Me (both of them in outstanding productions) surely were scheduled at least partly for their commercial appeal. Like all businesses, the festival has a bottom line. But it’s also come to realize that, especially in the two indoor theaters, which have much smaller capacities than the Elizabethan Stage, you don’t have to please all the customers with every show — and in fact, you can sometimes shake things up mightily, doing a few things that part of your audience doesn’t like at all.

To a wide-ranging theatergoer neither American Night nor Throne of Blood will seem especially radical, but both are exemplars of high-level contemporary dramatic achievement. American Night is a sort of alternate history of the United States, looking at things mostly from the viewpoint of the nonwhite and the dispossessed but somehow maintaining an essential optimism. Its rapid-fire vignettes range from a comic view of the Lewis and Clark expedition to union battles, Japanese-American detention camps, the Ku Klux Klan, the Mexican outlook on the Mexican-American War, a pretty hilarious cameo by a Bob Dylan sound-alike, and today’s border immigration raids. It’s a picaresque set up as a dream, and it’s theatrically engaging, with a small cast playing multiple roles (Rene Millan is the thoroughly sympathetic hero, preparing for his citizenship test) and a theatrical heritage that includes the likes of Dario Fo and Franca Rame, the San Francisco Mime Troupe, the Living Newspapers of the 1930s, silent-movie slapstick, and stand-up comedy. Inevitably the feel is a little scattershot, but it’s a buoyant scattering, and if it sometimes feels politically predictable it’s also refreshing — a good place to start this contemporary cycle of historic Americana.

To a wide-ranging theatergoer neither American Night nor Throne of Blood will seem especially radical, but both are exemplars of high-level contemporary dramatic achievement. American Night is a sort of alternate history of the United States, looking at things mostly from the viewpoint of the nonwhite and the dispossessed but somehow maintaining an essential optimism. Its rapid-fire vignettes range from a comic view of the Lewis and Clark expedition to union battles, Japanese-American detention camps, the Ku Klux Klan, the Mexican outlook on the Mexican-American War, a pretty hilarious cameo by a Bob Dylan sound-alike, and today’s border immigration raids. It’s a picaresque set up as a dream, and it’s theatrically engaging, with a small cast playing multiple roles (Rene Millan is the thoroughly sympathetic hero, preparing for his citizenship test) and a theatrical heritage that includes the likes of Dario Fo and Franca Rame, the San Francisco Mime Troupe, the Living Newspapers of the 1930s, silent-movie slapstick, and stand-up comedy. Inevitably the feel is a little scattershot, but it’s a buoyant scattering, and if it sometimes feels politically predictable it’s also refreshing — a good place to start this contemporary cycle of historic Americana.

Throne of Blood represents something perhaps more radical for a company that has always grounded itself in the literary qualities of the theater: a play which is almost purely a visual expression. When Kurosawa so audaciously reinvented Macbeth for the screen he was already recognized as a star of international cinema. Ping Chong also comes to the project as an established master, self-assured and at the height of his powers, knowing how to create visual poetry from simplicity and understanding the structure of the drama implicitly. When he uses video projections (Maya Ciarrocchi designed them) he does it not to startle or show off but because that’s the best way to achieve the effect he wants. Stefani Mar’s splendid feudal-Japanese costumes, Christopher Acebo’s spare set, Darren McCroom’s lighting and Todd Barton’s sound design are ravishingly unified, lending the production a mythic quality: This Throne of Blood is as much ancient Greek as it is Shakespearean or Japanese. It unfolds as a cinematic dream, 90 minutes without intermission, with Kevin Kenerly brilliantly at its center as Wasizu, the Macbeth figure, and the astonishing Ako, as Lady Asaji, his wife, providing the fluid, ritualistic Noh heart to the performance. Intriguingly, the production’s one shortcoming is the sometimes slapdash quality of the dialogue, which can seem so slangy and offhand that it breaks the rhythm of the unfolding visual tale.

In a way, all of this excitement takes the festival back to the future it interrupted in 1994, when its innate caution overtook its better judgment and it canceled its six-year commitment to a second, urban company in Portland (that company spun off on its own to become Portland Center Stage). Bowing out of Portland was a rare case of institutional regression. The potential of the two-city company was considerable: Portland would get Ashland’s professional polish, Ashland would get a needed dose of contemporary urban sensibility, Oregon would get a year-round professional company that could play much bigger than the state’s modest population base would ordinarily allow. The synergy should have been potent, but the commitment was tepid, and eventually Ashland pulled the plug. Fortunately it hired Appel, who came from an urban background in Indianapolis and was well tied in to the national theater scene. Then came Rauch, whose roots were in the sophisticated form of grassroots theater practiced by Los Angeles-based Cornerstone Theater Company, which he led and helped found, but who also directed for major regional companies across the country, and who seems to know just about everybody in the business. The urban edge, the eagerness to try fresh approaches, the impulse to expand the definition of what the festival community was without sacrificing what it had been, came full circle.

No, it’s not your Daddy’s festival anymore. But your Daddy just might be liking what he sees.

*

ILLUSTRATIONS, from top:

- Lord Kuniharu gathers his generals to hear the news of the rebellion in “Throne of Blood.” Photo: Jenny Graham.

- Prince Hal (John Tufts, left), heir to the throne, finds the company of Sir John Falstaff (David Kelly) preferable to court in “Henry IV, Part I.” Photo: Jenny Graham.

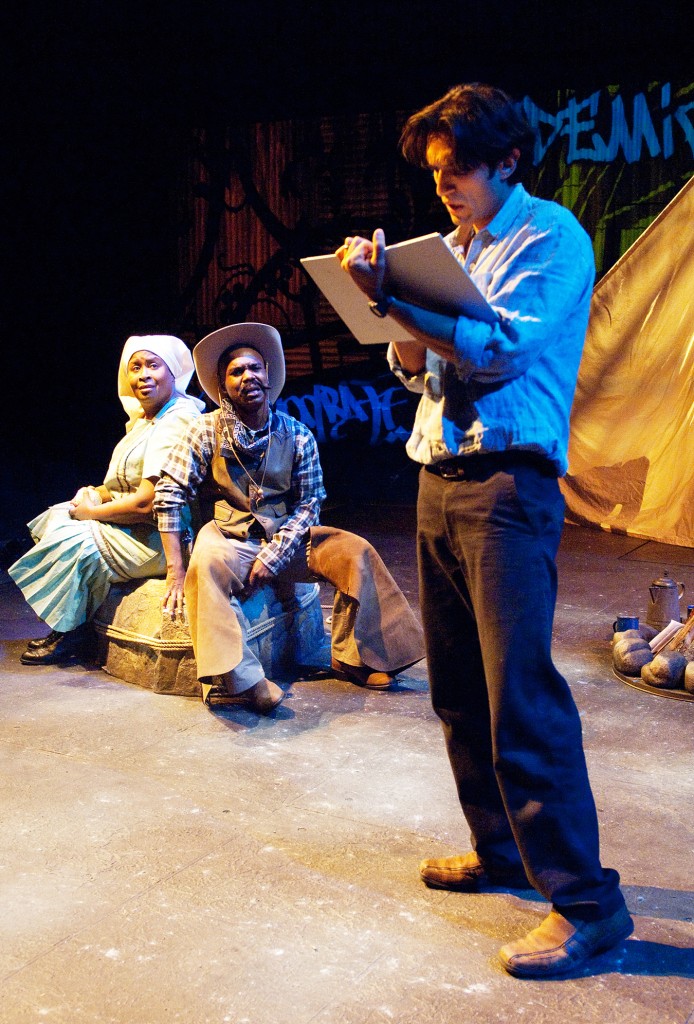

- Juan José (René Millán) adds to his history book after meeting Viola and Ben Pettus (Kimberly Scott, Rodney Gardiner) in “American Night.” Photo: Jenny Graham.

*

PREVIOUS POSTS on Ashland 2010:

- Ashland the first: night the twelfth. “Twelfth Night” plays for easy laughter on the open-air Elizabethan Stage.

- Ashland 2: pride, prejudice, ruin, respect. A smart and literary “Pride and Prejudice” in the Bowmer Theatre, the horrors of the Congolese war in Lynn Nottage’s “Ruined” in the New Theatre.

- Ashland 3: Hamlet the Fool. Dan Donohue is nobody’s — and everybody’s — fool in an extraordinary “Hamlet” in the Bowmer.

- Ashland 4: the quality of mercy, the surprise of love. Considering time and context in “The Merchant of Venice” and the musical “She Loves Me.”

- Does this blog make me look fat? Musicals, comedy and a true confession. Mrs. Scatter considers the charms of musical theater in general and “She Loves Me” in particular, and ponders the difficulty of comedy and why so many people can’t stand musicals.