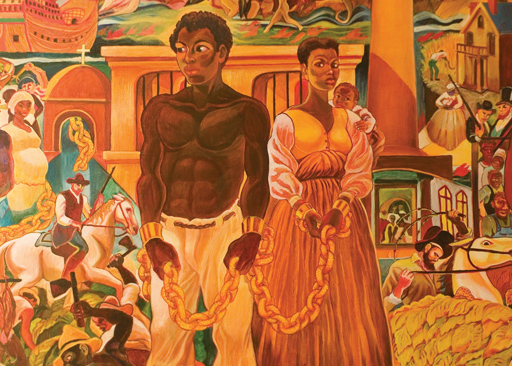

Ropes and chains and the piercing masts of slave ships at harbor pop up as boldly as the brilliant colors that command Arvie Smith‘s paintings in the exhibition “At Freedom’s Door.” Smith’s big oils of slave auctions and lynchings and other aspects of the bleak side of antebellum life are like jam-packed chapters in a vast historical novel bursting to be told. Some of his more satiric images are reminiscent of Robert Colescott, and his brown-yellow-red palette brings to mind some of the color combinations of fellow Portland artist Isaka Shamsud-din. But in their narrative urgency, their invocation of historical moment and their sometimes quizzical snatches of story (you get the feeling that you’ve been dropped into the middle of something, but you’re not quite sure where it started, although you have a good idea where it’s likely to end) Smith’s paintings also have a novelist’s sense: They make me think of Charles Johnson and his great American slave story of the beginnings of things, “Middle Passage.”

“At Freedom’s Door,” which also includes fabric art by Baltimorean Joan Gaither and the admirable Portland artist Adriene Cruz, was originally shown last year at Baltimore’s Reginald F. Lewis Museum, where Smith and Gaither were artists in residence. Now in the Feldman Gallery of Pacific Northwest College of Art through March 8, it’s one of a pair of provocative exhibits in Portland noncommercial galleries that commemorate Black History Month. The other, on view through March 2 at Reed College’s Cooley Gallery, is “Working History”, which features work by such nationally notable artists as Kara Walker, Io Palmer, Faith Ringgold, Kianga Ford, David Hammons and Nick Cave.

The combination of these three artists in “At Freedom’s Door” plays a nice ping-pong in your head, knocking you back and forth among varying aspects of the African American experience. And they represent three intriguingly different artistic sensibilities.

“Look at this,” Smith’s paintings say. “This is important.”

“Look closely at this,” Gaither’s text-stitched quilts say. “Things aren’t what they seem.”

“Look and listen and enjoy,” Cruz’s vibrant quilts say. “Life has wondrous things.”

Smith’s paintings also remind me in their novelistic quality of the writings of E.L. Doctorow, which are accordioned with character and incident: Think “Ragtime” from an intensely racial perspective. Here is a clutch of laughing white faces at a spectacle: It could be the circus coming to town on that three-master in the harbor. Except for the chains. And the manacled black legs hanging from the top of the frame, where a tree is just out of sight.

In another painting, more chains. A serpent twined around a tree. Shrouded black faces peering from the windows of a red-brick building. A top-hatted white man — a slave auctioneer? — standing center, with another man at one side of him, pulling on a chain that seems to be bearing a heavy weight, and on the other side a black child or woman, stoic-faced, playing a fiddle on command.

Or this one: A white Adam and Eve with an apple. Bosch-like scenes of sex and violence circling the outer edges, like the little profane images surrounding the central sacred image in a medieval illumination (a historical reference, by the way, also employed by Chris Ofili in his infamous and misunderstood elephant-dung-encrusted 1996 piece “The Holy Virgin Mary”).

Smith touches on the historically inflammatory issue of miscegenation in yet another large oil that depicts a clutch of runaway horses, a bare-breasted black woman keeping them barely under control. Beside them a black man, wearing a crown of bells, entwines his arms around an abstractedly satisfied white woman with a mask in one hand and her pubic patch showing through the gossamer of her flimsy dress. She smiles, as in a daze.

Finally: A huge, brutal painting of hooded Klansmen, stringing up a naked black man, with the red-and-white stripes of an American flag peeking from the upper corner. The execution of the man is stark, but the execution of the painting isn’t. The roiled colors of the sky. The fresh buds of new green growth on the Tree of Death. The almost living ripples and whorls, reminiscent of Thomas Hart Benton’s manly twists and rhythms, in the Klansmen’s sheets. The furtiveness of the eyes behind the eye slits. And — what’s this? — are those modern tennis shoes on one of the murderers’ feet? What century is this?

Part of the power of these paintings — and they are very powerful — comes from their unlikely fusion of painful subject matter and the pure pleasure to be found in fine and vigorous craftsmanship.

Gaither’s art is an altogether subtler thing. Taking the traditional women’s art forms of quilting and stitching, she embeds them with messages both broad and particular. Her 2007 quilt “(un) Conscious Collective Connotations,” for instance, is all white and pretty, with a string of pearls spelling out the word BLACK, in white: It’s there, but almost lost. Its matching quilt, all in velvety black, spells out WHITE — twice, both times in black. The racial dichotomy is there and not there, hidden and unmistakable.

A 2003 piece, all valentine-frilly, called “How Much Longer?” expands on the question with a series of stitched quotations: “We don’t do black hair.” “The white woman told my grandma, ‘If you put that hat on your head, no decent white woman can ever wear it.'”

The piece that stands out among Gaither’s works here, and demands despite its surface prettiness to be scrutinized like an essay or historical document, is a quilt stitched in the august gold of the law, and framed with golden feathers. On one side in large letters is stitched “MARYLAND THE FREE STATE CODE 1860 LAW.” This is, as the date makes clear, on the cusp of the War Between the States. In much smaller letters are rules, regulations, bannings and prices for Negro infractions, all spelled out with the inevitability of law. On the other side are images of chains, an American eagle, African figures and the following quotes stitched into the fabric: “What a strange civilization Maryland represented! Here was a society that somehow combined medieval traits like aristocratic traditions, a Catholic training, and the institution of slavery, with the most modern democratic political practices.” And: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness …” In a nutshell: The comfort of home handiwork, the discomfort of not forgetting.

Cruz is known nationally for her sensuous, undulating, richly colored meditation quilts, pieces that are at once mysterious and soothing and practical, and unabashedly in pursuit of beauty. Smith’s stern historicity and Gaither’s social politics may well be embedded in her work, but Cruz’s art primarily looks forward: It’s an embracing “yes” to life.

Her outstanding piece here, one that dances with the sophistication of the great piece of music that partly inspired it, is called “Dancing to Coltrane/A Love Supreme,” and it is literally that but also its own joyous creation, an embodiment of Cruz’s own spirit.

It’s interesting that of these three artists, the non-Northwesterner, Gaither, is the most contemporary and conceptual. Smith’s historical narratives, with their hint of muralism, and Cruz’s handiworks reshaped into artistic abstraction, share the firm rooting of so many Pacific Northwest artists in a sort of geological allegiance to the natural world around them. Conscious or unconscious, this is true of representational and abstract artists alike, from the Runquist brothers to Carl Morris to Lucinda Parker to Michael Brophy and James Lavadour. If it often leaves them misunderstood or ignored or written off as regionalists by the larger art world, this fundamental sense of the concrete also distinguishes them. Somehow, for many artists, black, white, or brown, this landscape is inescapable.

Cruz spells out this blending of the here and there in her artistic statement for this show: “‘Dancing to Coltrane/A Love Supreme’ is the memory of a spirit dance, a magical moment while driving along the Columbia Gorge. November 1995. Riding alone except for the music, the opening notes of ‘A Love Supreme’ accompanied the turn of a bend just as a spectacular vista presented itself … the river, the rolling hills, the sun shining bright, me on a mission of love to visit a dear friend … it was beauty, pure amazing beauty in complete harmony with the music. The synchronicity of the sounds, the visuals and my own spirit at that moment still amaze me.”

And then, a benediction: “I pray the blessings of the Ancestors continue.”

The ancestors who waited, in chains, at the ends of ropes, with little hope for themselves but hope for their children or children’s children or children’s children’s children. The ancestors, waiting to enter at freedom’s door.

— Bob Hicks