The primary piece of writing on my reading list this weekend was Inara Verzemnieks’ profile of Brad Cloepfil, which was a hybrid of sorts, marrying facts about the architect and his buildings, but also offering an account of life on the ground inside those buildings and an approach to thinking about his work. It even gets, gulp, philosophical. I was a little too close to the process of this story to supply a full-fledged analysis of it, let alone a “judgment”, but it is the jumping off point for the rest of this post.

The primary piece of writing on my reading list this weekend was Inara Verzemnieks’ profile of Brad Cloepfil, which was a hybrid of sorts, marrying facts about the architect and his buildings, but also offering an account of life on the ground inside those buildings and an approach to thinking about his work. It even gets, gulp, philosophical. I was a little too close to the process of this story to supply a full-fledged analysis of it, let alone a “judgment”, but it is the jumping off point for the rest of this post.

Lurking within Inara’s story is a debate between Ada Louise Huxtable and Nicolai Ouroussoff, and not just over Cloepfil’s renovation of the Museum of Arts and Design at 2 Columbus Circle, either. About everything. I’ll start with Huxtable just because she’s just the best. She puts Ouroussoff on notice immediately in the lead of her review in the Wall St. Journal: “the reviews have set some kind of record for irresponsible over-the-top building-bashing,” she writes, and she must be referring to him, because no one was quite as vitriolic as he was (that I’ve found in print, anyway).

So, why did Ouroussoff and others respond the way they did to Cloepfil’s building? “Mr. Cloepfil is a very cool, very restrained architect with a minimalist sensibility; his work is out of sync with a public increasingly desensitized by today’s can-you-top-this hypersensationalism and the expectation of in-your-face “icons.”” Which is basically what Cloepfil himself says in Inara’s story.

At a certain point, he [Cloepfil] said, he had looked around and realized that a lot of the celebrated architecture taking place “was about screaming, a kind of competition of novelty that I realized I would lose. That’s just not a conversation I can participate in — it’s not what I’m interested in. I’m not clever enough and quick enough and sensational enough, and so all I could do was identify … a kind of architecture that I thought people would hear. That there could be a counter-voice to the kind of excess and extremism that’s out there, you know — that kind of conservative thinking that says either it is or it isn’t … . And I use the word ‘quiet,’ but I don’t really mean it that way, because it’s hard to talk about this kind of work in a way that doesn’t make it sound diminutive … . I just think it’s incredible that something that is quiet and thoughtful and precise and introspective can be considered almost a radical act!”

That might sound a bit theoretical, but Inara is at her best explaining the effects Cloepfil’s buildings have on the ground, inside — which are startlingly complex, actually, to those of us who think of a room as four straight walls and a door. And here Huxtable, who actually has the same problem with Cloepfil’s building as Inara does (a band of restaurant windows added late by the client to the design), concurs again: “there is enchantment inside.” And I’m sure that has to do with Cloepfil’s considerations of “thresholds” and using “dichotomies” to explore “in-between” spaces and his recent thoughts about buildings as “disclosures”.

Ouroussoff’s utter condemnation in his New York Times review even tossed over Cloepfil’s careful consideration of interior spaces, calling them “poorly detailed” — citing two problems inside (the inclusion of strips of wood separating the glass channels from the floor, and some drywall that keeps the incision that is Cloepfil’s central gesture in the building from reading as a “continuous cut,” in Ouroussoff’s words). His judgment: “the project is a victory only for people who favor the safe and inoffensive and have always been squeamish about the frictions that give this city its vitality.”

Ouroussoff’s utter condemnation in his New York Times review even tossed over Cloepfil’s careful consideration of interior spaces, calling them “poorly detailed” — citing two problems inside (the inclusion of strips of wood separating the glass channels from the floor, and some drywall that keeps the incision that is Cloepfil’s central gesture in the building from reading as a “continuous cut,” in Ouroussoff’s words). His judgment: “the project is a victory only for people who favor the safe and inoffensive and have always been squeamish about the frictions that give this city its vitality.”

So, here, he must mean Ms. Huxtable? And just to make sure we got the message, he included 2 Columbus Circle in his list of buildings that he wishes could be destroyed, along with Trump Place, Madison Square Garden and several others. His indictment concludes: “a mild, overly polite renovation that obliterates the old while offering us nothing breathtakingly new.”

I have enjoyed how wide-ranging Ouroussoff has been in his choice of subjects to review for the NY Times. I suppose that’s a must — the biggest, boldest projects are rising in Asia these days or in renascent Europe, not the U.S. He writes an entertaining review, knows his way around a sharply turned phrase, enjoys being in the middle of things. But since his discussion of Cloepfil, I’ve been reading him a bit more carefully, because though I was willing to grant the “imperfect” nature of the renovation (Huxtable’s word), I didn’t see it as “timid” (Ouroussoff’s). Cloepfil is not timid. And in subsequent reviews, I think I’ve detected a pattern emerging, a simple one, a dichotomy if you will: the timid versus the bold. Anything that is bad is timid; anything that is good is bold, even revolutionary. But only when it suits his purposes.

Here’s his lead to a review in November of a proposal for a new museum in Berkeley, Calif., by Toyo Ito (pictured above): “I have no idea whether, in this dismal economic climate, the University of California will find the money to build its new art museum here. But if it fails, it will be a blow to those of us who champion provocative architecture in the United States.” A champion of provocative architecture. So, Ito is a provocateur? The model of the design shows a building that isn’t “square” or “glass”, that is inventive and interesting to look at, but hardly, post-Gehry, a provocation.

Ouroussoff then praises Ito for some of the same things that I would praise Cloepfil for: “For decades now, Mr. Ito has ranked among the leading architects who have reshaped the field by infusing their designs with the psychological, emotional and social dimensions that late Modernists and Post-Modernists ignored. They have replaced an architecture of purity with one of emotional extremes. The underlying aim is less an aesthetic one than a mission to create a more elastic, and therefore tolerant, environment.” Those pesky psychological, emotional and social dimensions! Those thresholds, those private spaces that open up to the rest of the world somehow!

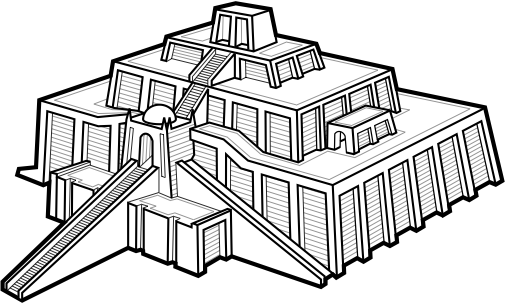

And then his latest review of I.M. Pei’s new Museum of Islamic Art in Doha, Qatar, a ziggurat on a man-made island, that gets very close to the same kitsch that infects designs up and down the Arabian peninsula, from Kuwait on down, the wavy buildings, the buildings that rotate, the new cities planned to look like Venice with an Arabian twist. Here’s the key line from Ouroussoff’s lead: “its clean, chiseled forms have a tranquillity that distinguishes it in an age that often seems trapped somewhere between gimmickry and a cloying nostalgia.” Yeah, but aren’t you the avowed champion of provocative gimmickry?

And then his latest review of I.M. Pei’s new Museum of Islamic Art in Doha, Qatar, a ziggurat on a man-made island, that gets very close to the same kitsch that infects designs up and down the Arabian peninsula, from Kuwait on down, the wavy buildings, the buildings that rotate, the new cities planned to look like Venice with an Arabian twist. Here’s the key line from Ouroussoff’s lead: “its clean, chiseled forms have a tranquillity that distinguishes it in an age that often seems trapped somewhere between gimmickry and a cloying nostalgia.” Yeah, but aren’t you the avowed champion of provocative gimmickry?

And then this amazing paragraph: “Many successful architects today are global nomads, sketching ideas on paper napkins as they jet from one city to another. In their designs they tend to be more interested in exposing cultural frictions — the clashing of social, political and economic forces that undergird contemporary society — than in offering visions of harmony.” Champion of provocative architecture? No way. Now he wants intimate harmony. Do these words mean anything?

And then this amazing paragraph: “Many successful architects today are global nomads, sketching ideas on paper napkins as they jet from one city to another. In their designs they tend to be more interested in exposing cultural frictions — the clashing of social, political and economic forces that undergird contemporary society — than in offering visions of harmony.” Champion of provocative architecture? No way. Now he wants intimate harmony. Do these words mean anything?

I’m sure they do. Ouroussoff is a smart guy, and if he were forced to in a court of law, he could come up with a dazzling set of explanations that would also chastise the likes of Art Scatter for even bringing it up. But I find it all a bit of a muddle, and I’m nothing if not an enemy of a “foolish consistency”. Now, if I were to visit Doha, then I might find Pei’s museum as charming and moving as Ouroussoff; I doubt it, but I might. I’ll undoubtedly get a kick out of Ito’s building if it ever gets built. It looks perfect for Berkeley somehow. And maybe I’d even agree with him about Cloepfil’s building, once inside it. But it’s not about agreement; it’s about intelligibility.

And so I find myself nodding as I read Huxtable and the phrase, “today’s can-you-top-this hypersensationalism and the expectation of in-your-face “icons””. Because I think Ouroussoff is part of the creation of the hypersensationalism and the instant icons, and his analysis is too indiscriminate to be convincing — what is good about it? And yes, he was part of the record-setting “irresponsible over-the-top building-bashing” that Huxtable describes, the leader of the pack when it came to 2 Columbus Circle, but on what ground? Surely not on the same ground on which he praised Ito or Pei and seemed to oppose gimcrackery and hypersensationalism himself. It doesn’t make sense to me.

And goodness knows we need an architecture critic we can trust, one with a decent travel budget. We’ve worried here about the totalitarian dimension of the fantasy architecture proposed and being built in the new global economic centers. And yes, I’ve shown my hand: In much of it I sense the same kitsch we see in 20th century totalitarian architecture, kitsch on a massive scale, kitsch beyond cute or even ironic. Evil kitsch, not the lava lamp in the closet. It’s provocative, I will grant. But as much as I am amazed by the energy this kind of capital formation can generate — the tallest buildings in the world! entirely new cities! — I am even more alarmed by the threat it suggests, this money without democracy. Of course, writing this at the end of 2008, financial institutions tattered and flapping in the wind, maybe the threat of capital formation will be the least of our problems.