By Bob Hicks

It’s possible Mr. Scatter should have kept his mouth shut.

There he was, scanning the shelves at the local outlet of a mega-mega multinational book store, when a man and his son approached, trailing a clerk behind them. The boy looked to be 10 or 11, and he and his father had seen something on television about a new movie version of Gulliver’s Travels coming out later this month (Jack Black stars as a travel writer on assignment to Bermuda), and they thought it’d be fun to read the book before they saw the movie. But what version?

“You probably want one of the adaptations,” the clerk said helpfully. “The language is modernized, and they’re a lot easier for kids to read than the original.”

“You probably want one of the adaptations,” the clerk said helpfully. “The language is modernized, and they’re a lot easier for kids to read than the original.”

Having fulfilled her function, she walked away, never having mentioned that most adaptations also snip out big uncomfortable chunks of the text.

Father and son stood undecided, not sure whether to go for the condensed version or the real thing.

“Buy the original,” Mr. Scatter found himself saying. “It’s lots better.”

Well, it is. Jonathan Swift‘s novel, first published in 1726 under the title Travels into Several Remote Nations of the World, in Four Parts, by Lemuel Gulliver, first a surgeon, and then a captain of several ships, is one of the most hacked-at and sanitized books ever written, and those are the versions, unfortunately, in which most people encounter it. That seems to be largely because its fantastical elements (little people, giants, talking horses, flying cities) tilt it toward the catch-all of children’s literature, despite its often coarse detail and sophisticated adult themes. It is, underneath the flimsiest tissue of whimsy, a scabrous satire on European morals and politics, and quite rude on the subject of bodily functions, and such things will never do for the young and tender-cheeked. (Nor is it the only book to be hogtied and forcibly hustled into the children’s playpen in spite of its original intentions. It’s a bit of a jolt to remember that the Grimm folk and fairy tales, which have been so resolutely cleansed and prettified for nursery and adolescent consumption in the almost 200 years since the brothers first published them, were themselves sanitized versions of older, even more savage folk traditions.) In brief: Take out the scruffy parts of Gulliver’s Travels and you’ve ripped out its heart and soul.

Still, it wasn’t Mr. Scatter’s call, as he realized when the gentleman smiled and thanked him and walked off with a copy of the real thing.

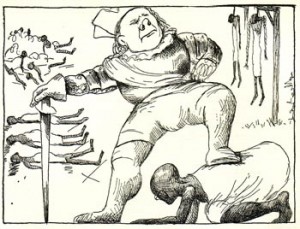

What had Mr. Scatter done? If a person’s goal is to keep the young innocents eternally innocent, giving a child this book as Swift wrote it is like hiring a wolf to babysit a flock of sheep. Did father or son have any idea what they were about to get into? Could Swift’s measured 18th century language possibly hold the lad’s interest? And what would the parental units think when the boy inevitably came to the infamous scene in which the giant Gulliver, faced with the emergency situation of dousing a fire engulfing the Liliputian palace, whips down his pants and unleashes his bladder on the flames below — a scene left out of most of the sanitized versions?

What had Mr. Scatter done? If a person’s goal is to keep the young innocents eternally innocent, giving a child this book as Swift wrote it is like hiring a wolf to babysit a flock of sheep. Did father or son have any idea what they were about to get into? Could Swift’s measured 18th century language possibly hold the lad’s interest? And what would the parental units think when the boy inevitably came to the infamous scene in which the giant Gulliver, faced with the emergency situation of dousing a fire engulfing the Liliputian palace, whips down his pants and unleashes his bladder on the flames below — a scene left out of most of the sanitized versions?

Mr. Scatter isn’t sure. But when he brought up this tricky moral situation with the Older Educated Daughter, she recalled reading Gulliver when she was about 12 and being both utterly unprepared for and utterly fascinated by the fire-fighting solution. That got Mr. Scatter to remembering when the OED was about 9 and visiting a book shop on Orcas Island in the San Juan chain. She curled up on the book shop’s floor with a thick and detailed version of the Greek myths (something far beyond Bulfinch) and, when she decided to buy it, was faced by a clerk determined to steer her instead to a simplified children’s version. The OED stubbornly held her ground, the clerk gave up with a sigh, and the OED proceeded, over the next several days, to devour the book. Later, at university, she studied classics and learned to read ancient Greek. There’s an argument to be made for the real stuff, and we can hope the good father and son, both of whom seemed pleasant and intelligent people, find their unexpurgated Gulliver both challenging and rewarding.

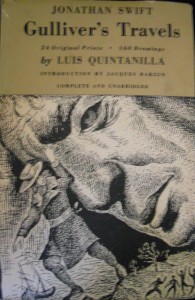

Mr. Scatter may have poked his nose into their business because, by coincidence, he had just finished re-reading Gulliver, in a 1947 edition he’d picked up at Powell’s City of Books that includes 160 drawings and 24 prints by the Spanish illustrator Luis Quintanilla. It was one of those terrific Powell’s finds: a fine book in an excellent edition, well-preserved, and just $14.95. Old expurgated editions can cost a lot more, and in this case, Quintanilla’s drawings are so well-matched to the narrative that they seem an organic aspect of it.

Mr. Scatter may have poked his nose into their business because, by coincidence, he had just finished re-reading Gulliver, in a 1947 edition he’d picked up at Powell’s City of Books that includes 160 drawings and 24 prints by the Spanish illustrator Luis Quintanilla. It was one of those terrific Powell’s finds: a fine book in an excellent edition, well-preserved, and just $14.95. Old expurgated editions can cost a lot more, and in this case, Quintanilla’s drawings are so well-matched to the narrative that they seem an organic aspect of it.

Quintanilla is an intriguing figure, an excellent draftsman and finely calibrated satirist who had lived the sort of life that gave depth and vigor to his drawings. Born in 1893, he moved to Paris in 1912 and three years later, as France was enveloped in war, returned to neutral Spain. During the teens and ’20s he became friends with Hemingway (his son, in a timeline of Quintanella’s life and career, says it was his father who first told Hemingway about the running of the bulls in Pamplona) and several of the leaders of what would become the Spanish Republic. In 1934 he was arrested for being a member of the Revolutionary Committee, and became an international cause celebre, with writers and intellectuals from Malraux to Dos Passos pushing for his release. Freed after about eight months, he later criss-crossed the war zone making drawings, and in 1938 did a series of drawings satirizing Franco and the fascists. In 1939 he left for the United States and a 37-year exile that would last until 1976, when he returned to Spain. Two years later, he died.

In other words, Quintanilla had experienced much of the worst that Europe had to offer. And when Crown Publishers conceived of this project shortly after the end of World War II, a fresh look at Swift’s masterpiece must have seemed potent and timely. It was no good time to forget the forces that had plunged the world into a savage war, and Swift was there with some incisive reminders. The ferocity of the Yahoos and the inadequacy of the rationalist Houyhnhnms had just been forcibly illustrated. The jet fighters and flying bombers that wreaked havoc from the skies made the airborne capital city of Laputa seem less a matter of fantasy or science fiction than just another report from the laboratories and factories of technological advancement. And in a world in which the sub-microscopic secrets of the atom had resulted in a resoundingly macroscopic destructive bang, Gulliver’s startling encounters with scale in his sojourns with the Lilliputians and the Brobdingnagians might have seemed prophetic. Swift provided an explanation for the horrors that the “civilized” world had just encountered, and also, in a strange way, a measure of solace, because no such savage satire is possible without a corresponding desire for social and moral correction. By the conclusion of his tales, Gulliver might have curdled into a sort of hermetic lunacy. Swift, his creator, had not.

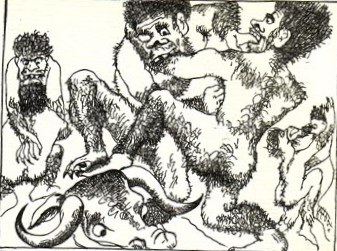

With this edition, Quintanilla seems to have captured the rudely physical spirit of his book in much the way that Robert Crumb unearthed the extreme physicality of the scriptural tales in his Book of Genesis. In both cases, apparently fantastical stories are rooted in the corruptible realities of the flesh. And in Quintanilla’s case, those realities reflect Gulliver’s view of human history as “… an heap of conspiracies, rebellions, murders, massacres, revolutions, banishments, the very worst effects that avarice, faction, hypocrisy, perfidiousness, cruelty, rage, madness, hatred, envy, lust, malice or ambition could produce.”

With this edition, Quintanilla seems to have captured the rudely physical spirit of his book in much the way that Robert Crumb unearthed the extreme physicality of the scriptural tales in his Book of Genesis. In both cases, apparently fantastical stories are rooted in the corruptible realities of the flesh. And in Quintanilla’s case, those realities reflect Gulliver’s view of human history as “… an heap of conspiracies, rebellions, murders, massacres, revolutions, banishments, the very worst effects that avarice, faction, hypocrisy, perfidiousness, cruelty, rage, madness, hatred, envy, lust, malice or ambition could produce.”

We are, after all, only human. And if that’s not a children’s story, it’s a great one for growing up. Any bets on how Jack Black’s going to handle such a rude reality in Bermuda?

*

ILLUSTRATIONS, from top:

- Luis Quintanilla, illustrator, Yahoos fighting, “Gulliver’s Travels,” Crown Publishers 1947.

- Dust jacket for the Quintanilla edition, which has an introduction by Jacques Barzun.

- Luis Quintanilla: Gulliver quenching the Fire in the Royal Quarters of the Empress.

- Luis Quintanilla: Gulliver petted and fondled by the Brobdingnag queen’s maids of honor.

- Luis Quintanilla: Gulliver Explains European Politics to the Houyhnhnms.