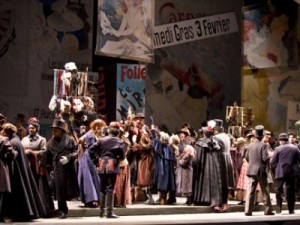

Let’s have a party: Alyson Cambridge fires up the menfolk as flirtatious Musetta in Puccini’s “La Boheme.” Photo: Portland Opera

Art Scatter remembers a time in Portland when the cornucopia of performance was overflowing and Friday evenings confronted culture-hoppers with the sobering reality that despite theoretical breakthroughs in physics and mathematics, mere human beings can still be in only one place at a time.

Oh, wait: That time appears to be now.

Last night saw the openings of the rich American musical Ragtime at Portland Center Stage, the smart playwright Steven Dietz’s comedy Becky’s New Car at Artists Rep, The Indie Concert with leading contemporary dancemakers Mary Oslund and Gregg Bielemeier at Conduit (this one has just one more performance, tonight), acerbic comedian Lewis Black at the Schnitz, Alfred Uhry’s Tony-winning The Last Night at Ballyhoo at Clackamas Rep, and the return of Stephen Sondheim’s modern classic Company at the Winningstad Theatre. Plus some other stuff.

Where to go? What to do?

We went for the guts with Portland Opera’s season-opening performance of Giacomo Puccini’s La Boheme, and came away with the glory, too: a lovely, funny, moving production of one of the most glorious operas ever written.

We went for the guts with Portland Opera’s season-opening performance of Giacomo Puccini’s La Boheme, and came away with the glory, too: a lovely, funny, moving production of one of the most glorious operas ever written.

There are those who declare loudly that the 19th century came to a close in 1924 when Puccini died at age 65, and that for all practical purposes opera died with him.

That’s turned out to be a gross misunderstanding of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, both culturally and musically. (When I told a prominent but somewhat ossified classical critic many years ago how much I’d enjoyed the Bartok I’d heard the night before, he snorted and replied: “No, you didn’t. Nobody enjoys Bartok. They only say they enjoy Bartok because they think they’re supposed to enjoy Bartok.”)

Portland Opera’s production, directed by Sandra Bernhard and featuring the gorgeous-toned Kelly Kaduce as the beautiful consumptive Mimi, reminded me that classics are of their own time and place: Boheme, which debuted in Turin, Italy, in 1896, revels in a romanticism and a deep love for melody that simply don’t exist in the contemporary arts vocabulary.

But this production also reminded me that classics (speaking of theories of relativity) don’t age. They are classic because they remain fresh. In Boheme‘s case it stays fresh because even though Puccini’s kind of romanticism seems a thing of the past, it is also buried deep in our aesthetic bones: We can’t escape it, and we don’t really want to.

Christopher Mattaliano, Portland Opera’s general manager, makes an interesting case in his program notes for Puccini’s essential modernity:

“His music has become so ubiquitous and his popularity so great that one may forget how truly original he was as an artist.

“He absorbed the modern compositional trends of his time — the use of non-traditional sounds (bells, chimes, sirens, etc.), the experiments in orchestral color and texture being used by Debussy, Mussorgsky and others, and the use of thematic material (think Wagner’s leitmotif) — without becoming a slave to any of it.

“Of course, he also had a natural gift for melody — soaring, irresistible melody, which is what most people associate with his work, and why he’s so popular with the public.

“But all of the above had a singular purpose with Puccini — to serve the drama. … He was an innate man of the theater, and his understanding of theatrical timing and effect is unsurpassed.”

I’ll leave it to others to file detailed reviews of the production (The Oregonian’s David Stabler and Barry Johnson have already turned in their glowing reports on Oregon Live, and blogger/writer extraordinaire Marc Acito has posted his on-the-spot reactions, too) and finish with a few observations:

- Puccini a consummate man of the theater? Spot on. I noticed it immediately, with the first notes from the orchestra under conductor Antonello Allemandi’s assertive baton. A lot of operas use the overture to sneak softly into the music’s themes, tiptoeing toward previews of coming attractions. Boheme opens with a dramatic bang, as vivid and bold and colorful as the paints on bohemian artist Marcello’s canvas.

- It’s sad and all that — we all know Mimi dies — but Boheme also has some very funny stretches. Stage director Bernhard plays that up especially in the second-act crowd scenes, and particularly in flirtatious Musetta’s campy frolicking in the restaurant, when her outrageous narcissistic manipulations create a tension of conflict with the soaring beauty of her song, which on record can sound like the essence of purity. This lively act as staged here reflects some of the sly cultural observation of social caricaturists such as Daumier and Toulouse-Lautrec.

- When do you turn the music off? In Puccini’s shrewd reckoning, right at the end, when Mimi dies. Until that point, the entire opera, even moments of inconsequential dialogue, is fully sung. So when the emotional climax of the evening hits — when everyone except her lover Rodolfo realizes Mimi has died — the singing stops. And the quiet — the stripped-down, simple, unadorned speaking — becomes in its contrast the most eloquent music possible. That’s contemporary. And that’s classic.

——————————-

First inset photo: Oh that this too too solid flesh should fail: Mimi (Kelly Kaduce) and Rodolfo (Arturo Chacon-Cruz) comfort one another as the end nears. Portland Opera.

Second inset photo: Seventy-six trombones and a street parade: the colorful hijinks of Act II. Portland Opera.