This morning I discovered via Facebook feed that the great American literary sensation Nancy Drew is 85 years old, making her quite possibly the oldest 16-year-old super sleuth in history. That got me to searching for this story, which ran originally in The Oregonian on October 12, 1997. A revised version later ran in the late, lamented magazine Biblio.

________________________________________________

Here’s to you, Nancy Drew. You were my first true love. My first safe true love.

Sure, there were others. Freckled Norwegian girls with hair like hay and eyes as swift as mountain streams. Lipsticked, rounded girls in cashmere sweaters that clung to peach-soft skin. Porcelain dolls of unapproachable sophistication. But they were dangerous, because they were real, and liable to utterly destroy the hesitant intentions of an awkward boy.

Ah, but you, you forthright, striding, titian-haired marvel. You, you crime-busting beauty in your little blue roadster.

You were a flash, an action. A wonderful blank, waiting to be filled in. Made of printer’s ink and imagination, you were the speeding American vision of a bright future. An ideal, a fantasy, a goal. You were not for attaining. You were for setting the standard. You were the New American Woman.

Thank heavens for the printed page. With real girls, I was pretty much doomed to be tongue-tied and star-struck. With you, I had a relationship. And it was about all sorts of things, perhaps the least of which was puppy love (you were not, essentially, romantic, though you were a creature of romance). It was about literature and the secrets of writing. It was about boldness and courage and the declaration of self. It was about waking to the possibilities of a bigger world. It was about laughter and embracing the ability to enjoy. It was about doing right and fighting wrong. It was, in several pertinent senses, about growing up.

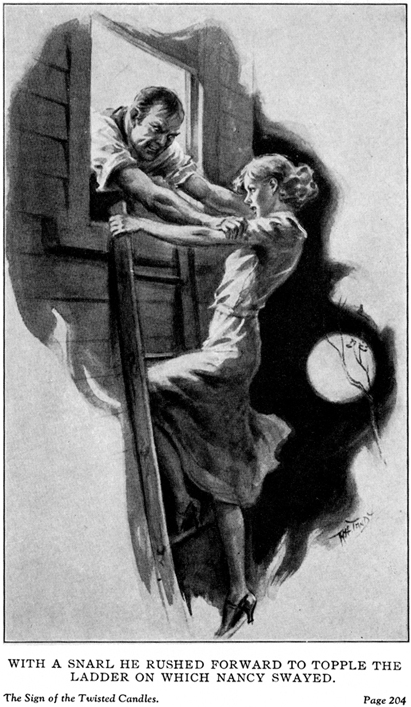

Not, of course, that I realized it at the time. At the time you were just a darned good read, a queen of the cliffhanger. How, in The Secret of the Old Clock (the very first Nancy Drew mystery, published in 1930), would you get out of the closet where the vicious thief Sid had locked you so he could make his getaway? Why, in The Hidden Window Mystery (No. 34), does Luke cry out in terror when you start to pull the lever to the trap door in the haunted house?

The pseudonymous writer Carolyn Keene resolved such questions quickly, but they were no less gripping when stumbled across on the page, most typically at the end of a chapter.

*

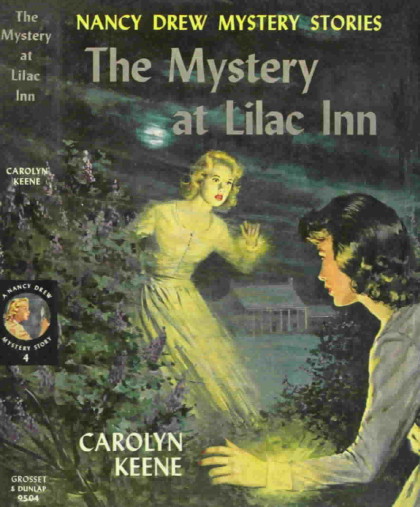

Things both odd and obvious trip us into memory. My madeleine, in this case, was straightforward: news that Portland’s Northwest Children’s Theater proposed to produce a stage adaptation called Nancy Drew: Girl Detective, a loose adaptation of The Clue of the Dancing Puppets and The Mystery at Lilac Inn.

Ah, a new generation cluing in to Nancy Drew! What a marvelous idea!

it isn’t so much a revival as a continuation, because Nancy has never stopped. From the famous original blue covers (now worth a minor mint as collectors’ editions), to the splashy graphics of the ’50s and ’60s, through the wretched mistake of The Nancy Drew Files in the ’80s and on to this decade’s sort-of return to the classic format, Nancy has sold more than 80 million copies in 17 languages.

By the time of Crime in the Queen’s Court (No. 112, published in 1993), the girl detective’s shiny blue roadster has become a perky blue Mustang. But she’s still sniffing out wrongdoing, still poking her nose into other people’s business, still hurling herself into physical danger and escaping through pluck, luck and quick wits.

In nearly 70 years she’s grown from a high-spirited, independent 16-year-old into a high-spirited, independent 18-year-old. Her dad, the famous criminal lawyer Carson Drew, is still flying out of town on important business and smiling benignly on his daughter’s escapades. Her doting housekeeper, Hannah Gruen, is still fixing late snacks and wringing her hands anxiously over Nancy’s impetuousness.

Athletic George and pudgy Bess are still palling around with Nancy in the endless summer of upper-crust River Heights, and Ned, her college-age boyfriend, still hangs around the edges of the pages, there as an abstract but rarely really playing a role in the poised teen-age supersleuth’s everyday life. Somehow, this diamond-tiara child of the Depression has emerged unscathed and barely aged amid the new-money hustle of the Silicon Society.

*

Let me propose an idea: Nancy Drew is Katharine Hepburn. Or maybe her younger sister.

Marie Curie, Amelia Earhart and thousands of other women may have accomplished more in real life. But how many have done more than Hepburn and Drew to popularize the notion of the New Woman, unfettered by custom or the whims of men? How many woman pilots, engineers, firefighters, lawyers, business executives would there be without the splendid example these two set? How many men would still be pining for a meek little ego-builder instead of marrying a challenger, a prodder, an intellectual partner?

It’s no surprise that in her most famous roles, Hepburn starred opposite two of the strongest men in movie history: Spencer Tracy and Cary Grant. Few other actors could stand up to the energy, stamina and sheer capability that was as inseparable a part of Hepburn as her regal air.

Katharine Hepburn and Nancy Drew are simply more accomplished than anyone around them. Nancy is a crack horsewoman (The Secret of Shadow Ranch, No. 5). Hepburn is a sportswoman who excels at everything from tennis to golf (Pat and Mike). Nancy is a smooth, spur-of-the-moment actress who makes up stories easily in pursuit of vital information. Hepburn slips into a screwball disguise in pursuit of her goal (Bringing Up Baby). Nancy is an expert on everything from the habits of homing pigeons (Password to Larkspur Lane, No. 10) to medieval stained glass (The Hidden Window Mystery, No. 34). Hepburn is a world-class lawyer (Adam’s Rib) and political reporter (Woman of the Year).

Financially, both are considerably better than well-off. It never bothered me that Nancy was rich. Like Hepburn in Holiday and The Philadelphia Story, and like the young noblefolk in Shakespeare’s comedies, that simply eliminates economic concerns so that true character can be revealed. Despite the protestations of Marxist critics, it’s also a pretty attractive fantasy. Who wouldn’t like the freedom to fly on a whim to an Arizona dude ranch or buzz up to the lake for a summer holiday or check into a luxury hotel?

And when it comes to respect, Hepburn has nothing on Drew. Criminals instinctively fear her powers of deduction. Police, politicians and other adults lean forward intently while she speaks, and trust her judgment implicitly: They spring to action to carry forward her plans.

Young and female, Nancy simply ignores the possibility that either accident might be an impairment in doing exactly what she wants; and, miraculously, neither is. Like the grand Hepburn, she blithely rewrites society’s rules, creating a deliciously free reality for herself and pointing the way for others to follow in her steps. Boo! Go away, you fusty old traditions and prejudices. I am a woman. I am a force of nature. I am at least your equal. I will do as I wish.

The Drew-as-Hepburn thesis has another side, too. Dorothy Parker, writing about Hepburn’s performance in the play The Lake, famously wrote that “she ran the whole gamut of emotions from A to B.” In Hepburn’s case, Parker was a better quipster than a critic. But in hard cold fact, Nancy Drew never gets much farther through the alphabet. She is a concept, an action, an exciting predictability. She has little inner life. Like Dick Francis’s likably interchangeable heroes in his racecourse mysteries, she will encounter physical danger, she will outthink her opponent, she will take the moral high road, and she will prevail. But she is no Hamlet. No one will ever argue about her peculiarities of personality or her motivations. Nancy acts, therefore she is.

*

For some reason the Hardy Boys, who were supposed to be the boys’ alternative to Nancy Drew, never rang my chimes. I ate up John R. Tunis’s exciting, moralistic sports stories (Iron Duke, Highpockets) and Robert A. Heinlein’s zoomy space operas and, of course, at an earlier age, the adventures of that porcine platitudinizer, Freddy the Pig. All of this pulp mixed together in a narrative stew with the likes of Gulliver, Huck Finn, Jim Hawkins, ancient Greek heroes, Atticus Finch, 1984, Sport magazine, Readers’ Digest Condensed Books, Tortilla Flat and William Faulkner’s Yoknapatawpha County to create an emerging sense of literary style and possibility.

In my crowded household, everyone read: With nine bodies and not much space, it was the best way to gain a little privacy. And often, what one kid brought into the house, others would end up reading, too. One of my sisters, 19 months older, always seemed to have a Nancy Drew or a Trixie Belden hanging around. And pretty soon I was like a hawk at a rabbit hole, circling impatiently for her to finish the latest so I could get my claws into it.

Not that I would ever take a Nancy Drew out of the house. In those days boys were boys and girls were girls, and being caught by the guys with a “girl” book in your hands would have been as mortifying and unthinkable as being caught playing with dolls. So Nancy became a private obsession, indulged only at home and never talked about with anyone else. (How many other younger brothers went to similar lengths to hide their own secret obsessions with the girl detective?)

*

They say you can’t go home again, and sometimes they’re right. Revisited, the romanticized past can seem a dull, shrunken, tattered place. Rereading Nancy Drew, I began to see pulp and tired plotting where once I had seen sparkle and adventure. The writing seemed flattened, perfunctory, formulaic. Why had I enjoyed these books so much? Was my memory that faulty, or was it just that the stories weren’t written for the benefit of a 49-year-old man?

A bit of both, and more. Many writers have slipped inside the name “Carolyn Keene,” which was dreamed up by an editor named Edward Stratemeyer, who plotted the first four books and then turned over the series (along with such others as the Bobbsey Twins and the Hardy Boys) to ghostwriters.

One woman, Mildred Wirt Benson, wrote 22 of the first 25 Nancy Drew adventures. In the ’50s, Stratemeyer’s daughter, Harriet Adams, became supervisor and final editor. She also rigorously rewrote all of the early stories for a “modern” audience, eliminating a few quaint references and some uncomfortable racial stereotyping but also scrubbing away much of the individuality and style that Benson achieved.

For a while, things got even worse. In the ’80s a horrible mistake called The Nancy Drew Files occurred, in which the teen sleuth was unnaturally grafted onto a gothic romance format. In their eager pursuit of the Sassy generation, the series’ writers lost sight of the all-important fact that the essence of Nancy is a dynamo, but also a virgin.

Nancy started paying attention to her suntan and her nails, and she began to wonder whether she should tone down her assertiveness so she could hang on to handsome hunk Ned. In Fatal Attraction (Nancy Drew Files, Case 22, 1988) our proud Katharine Hepburn turns into a cut-rate Morgan Fairchild:

“Ned poured some lotion into his hand and began to smooth it gently on her bare shoulders. After a minute he bent forward and kissed the tip of her ear. `How about if I drive you into River Heights tonight?’ His voice was as soft and gentle as his fingertips.”

Balderdash. How could such a literary perversion have come to be?

*

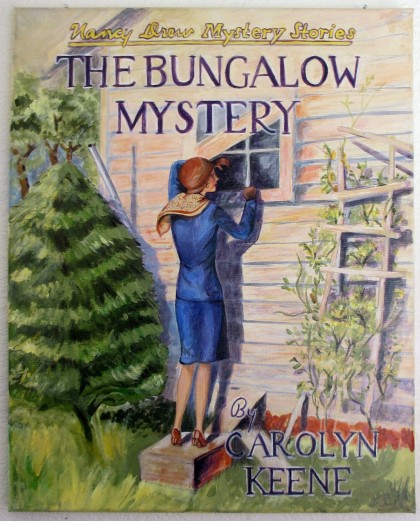

Then I picked up the third story, The Bungalow Mystery, in Mildred Wirt Benson’s original 1930 version. And there I was. Home.

In its original, the mystery has vivacity, sparkle, wit and style. It is plainly the work of a storyteller who understands not just plotting, but also the pleasure of putting the particular proper word in the particular proper place, creating the particular creative combinations that raise mere extended writing into literature. Yes, it’s juvenile literature, conceived on a small scale and tethered to the necessities of its pell-mell plot. But it manages an economy of language and flavor of style that place it in the same family, if lower at the table, with Ernest Hemingway.

Here’s how Carolyn Keene opens The Bungalow Mystery:

“ `Don’t you think we should turn back, Helen? It’s getting dreadfully dark out here on the lake and I don’t like the look of those big black clouds.’

“As Nancy Drew addressed her chum, Helen Corning, she gazed anxiously up at the sky and then out across a long expanse of water to the distant shore.”

Here’s how Hemingway opens “The Old Man and the Sea”:

“He was an old man who fished alone in a skiff in the Gulf Stream and he had gone eighty-four days now without taking a fish. In the first forty days a boy had been with him. But after forty days without a fish the boy’s parents had told him that the old man was now definitely and finally salao, which is the worst form of unlucky, and the boy had gone at their orders in another boat which caught three good fish the first week.”

Two books, two direct declarative approaches, two quickly established styles, two easy evocations of portent and danger.

There is much humor in the composed breathlessness of The Bungalow Mystery, and a few outright, if unintended, laughs. What tips Nancy off that the man pretending to be Jacob Aborn, guardian to her friend Laura Pendleton, is actually the evil impostor Stumpy Dowd? He doesn’t have a single servant, he makes Laura clean the house, he won’t give Laura spending money or let her shop for clothes. Then, in Laura’s words: “You haven’t heard the worst. He even took my fur coat away from me.”

Poor match girl! Insufferable villain!

*

Of course, Hollywood has learned a tough lesson about young heroines: They don’t sell. Girls will go to see a “boy” movie, but boys won’t go to see a “girl” movie.

It’s usually true with books, too: If they’re about girls, the boys are outta here. So half of young Americans miss out on Pippi Longstocking, Little Women, Ramona Quimby.

Their loss. And without these literary avatars of feminism, how will they recognize their Katharine Hepburn when she happens along?

So here’s to you, Nancy Drew. I was never Ned, and I will not whisper seductively or nibble your ear. I know you’ll modestly claim you didn’t really do much. But thanks for the good times.