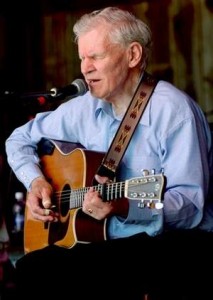

The inimitable Doc Watson died today at age 89. He was an American original, partly by being a true American traditionalist. I love his music and my idea, at least, of who he was. I wrote the following piece on him for The Oregonian, where it ran on June 1, 1997. I’d change a few things if I were writing it today, but it’s still worth a look if you knew Doc’s music, or if you didn’t but wish you had:

By Bob Hicks

On Father’s Day, the deep past visits Portland. And maybe, as popular music seeks a way out of its morass of superstardom, the future will too. Because try as we might to pretend it never happened, the past is part of us, and it shapes what we will be.

Thank goodness Doc Watson is helping to carry it.

Thank goodness Doc Watson is helping to carry it.

American music rarely sounds better than when Watson plays it. His easy-gliding voice is as fresh and sweet as the first bite of a mountain apple, and he is very likely the finest, most influential flat-top guitarist of his era.

He is, in short, a legend. But as far as popular musical consciousness goes, he is also, like the grand tradition of American optimism that he represents, in danger of fading away.

Semiretired since his son and partner Merle died in a tractor accident in 1985, Watson is about to make his first Portland appearance in eight years. On June 15, two days after opening this year’s Britt Festivals in Jacksonville, he’ll play a barbecue picnic at Oaks Amusement Park. And he will carry on his aging and unassuming shoulders the strength and possibilities of time itself.

At 74, Watson is a bridge back to the sounds and ideals from which we sprang: Irish-Scottish folk ballads, African-American field songs, Delta blues, mountain-fiddling tunes from Saturday-night dances and back-porch gatherings, age-old lullabies, church songs, Civil War stories, railroad songs, even Tin Pan Alley tunes and rockabilly.

Good music comes from someplace, and Watson’s is redolent of community — of people who share experiences, outlooks, territories. The specific someplace most important in the forming of his music is the Southern hill country that produced scratch farmers, cotton pickers, coal miners and string bands.

Listen to the high humor and plain poetry in his 1962 recording of the traditional song “Sweet Heaven When I Die.” It’s a song pregnant with the measured dreams and practical desires of a people used to having hard dirt beneath their fingernails:

“Beef steak when I’m hungry. Whiskey when I’m dry. Greenbacks when I’m hard up. Sweet Heaven when I die.” Or listen, from the same set, to the way that Doc’s amazingly fluid guitar picks the lead fiddle line to “Carroll County Blues,” sliding and chopping in perfect synchronicity along with fiddler Fred Price. This is a Watson trademark: the guitar as a narrative, melody-carrying instrument. And it’s a show of virtuosity all the more incredible because it sounds so easy.

Unquestionably, Watson is a keeper of the past. We can hope he helps carry us into the future, because American popular music is in crisis.

True, in some ways it’s thriving. Fine musicians playing in a plenitude of styles and traditions pack the highways, beating from town to town and club to club. World music is beginning to have an effect much bigger than its pallid sales. Every city has its own band of musical stalwarts — people such as Portland’s Janice Scroggins, Jim Mesi, Kelly Joe Phelps, Ron Steen and Rebecca Kilgore. But these keepers of America’s music are practically ignored by a business in which almost anything but musicality counts.

The main stream of pop has been ripped from its roots, turned shallow and so commodified that a person can hardly flick the radio dial without fear and trembling. In the age of arena rock, it’s the light show, the lewd lyrics, the tattoos, the decibels, the attitude that win the big payday: the adolescent up-yours of kids whose pocket change calls the tune of a billion-dollar industry. Rap has rejected its original social consciousness in favor of prepackaged poses. Jazz is massively ignored. Nashville is a rhinestone cliche. From CD jackets to huge outdoor stages, manufactured rebels pout in unison, packing their tirades to the bank.

And somewhere, someone is searching for the one thing that’s been left out of the carefully contrived package: the actual music.

For that person, slowing down and listening to Doc Watson would be an excellent place to start.

Blind after birth

Watson’s story is so deeply American you could write a ballad about it. One of nine children, he was born March 3, 1923, in Deep Gap, N.C., son of a banjo-playing farmer and a mother who sang. Soon after, young Arthel, as he was christened, began to go blind.

Doc thus became another in a line of fine American musicians who happened not to be able to see, from Blind Lemon Jefferson to Ray Charles to Stevie Wonder. Add George Banman Grayson, the blind fiddler from the ’20s who was a friend of Doc’s banjo-playing father-in-law, Carlton Gaither.

Grayson is a stitch in the complex quilt of community that helped produce Doc Watson the artist. The fiddler was kin to the Sheriff Grayson who captured the killer Tom Dooley, whose family the Watsons knew. Dooley’s story became a national sensation through a watered-down ballad by the Kingston Trio that helped spark the great folk revival of the late 1950s. And it was that revival that led serious musical students back into the woods and valleys and deltas of the South, looking for true traditional players.

One of those earnest scholars, Ralph Rinzler, discovered Watson, who was scratching out a living playing lead electric guitar in a rockabilly band in nearby Johnson City, Tenn.

Self-taught virtuoso

Far from the star-making machinery of the music industry, Watson had plenty of time to work on what really counted: the music itself. He had taught himself to play guitar and mandolin, and somewhere along the way he picked up enough banjo to be legitimately considered a virtuoso.

Some of what Watson has recorded sounds literally from another century, such as “East Virginia,” whose oddly inverted lyrics seem from an earlier version of the English language:

“I was born in old East Virginia, North Carolina did I go. There I courted a fair young lady, what was her age I do not know.” It sounds like ancient hills: a stretched-line vocal, flat and weary and bursting the seams of its scansion. Hearing the likes of this song is jolting and invigorating. It takes you to another place, another age, another way of envisioning life. But you won’t hear it in the arena.

The big money of modern music rejects skill and subtlety in favor of the obvious, the outrageous and the merely novel. It detests yesterday, because if you remember yesterday, you might not buy today’s new sensation, which will be old and forgotten tomorrow. Rock culture — at least at its highest, most hyped layer — has perverted the natural process, in which you get famous because you’re good. No wonder the musical pumpkin has been smashed.

Watson never bought in. Instead, he developed the two things an artist needs: a strong community of tradition, and the ambition to look beyond it to the bigger world. His music has some deep influences, among them Mississippi John Hurt, the Delta blues singer, and Jimmie Rodgers, the yodeling railroad man. You can hear other voices, from Bill Monroe to Maybelle Carter to Bob Wills, the king of country swing. The hollers, hymns and blues of the black South are there, too. But Watson is most remarkable for taking his many influences and transforming them into his own bubbling stew of American styles and cultures.

Think of the way he adapts Rodgers’ famous yodel, refashioning it from an exuberant whoop of a coda into part of the song itself: a sudden sliding falsetto that then drops back to the main line. It’s as if he’s so tickled by the music, he just can’t help himself.

That, too, is a Watson trademark: His music is a river running with humor. His darkest lament and most mournful wail are just a jump-beat away from unbounded joy. And how many musicians give their audiences the gift of joy?

Wisdom of the masses

Singing through the cynicism of a jaded age, Watson speaks to the old, discredited strain of American optimism — not as a sentimentalist but as a practical man seeking to live a full and satisfying life. His music is a balm. It understands the sweetness of endurance. It engages the mystery that is life.

The Doc Watsons of the world are the hope of the democratic experiment — the belief that, left alone, common people will discover not only what is right, but also what is beautiful. No matter how hard the opposite is hyped.

People defend the nihilism and curdled self-obsession of modern music by pointing to the excesses and sins of the culture that produces it. Maybe. But if hardship is the litmus, how do you explain the mountain music that shaped Doc Watson? This is music from a time and place without electricity or plumbing, endured by people who worked hard and lived short. Yet their music reflected joy, humor, purpose and a sophisticated view of the varieties of human experience.

It seems fitting that Watson arrives in Portland on Father’s Day, because the learning, refining and passing on of traditions has been his life’s work. This is the way life, and music, ought to be: changing and freshening, but building on what has come before. Good music is meant to be heard not in an arena, but by a small crowd at a time, with everybody close to touching range. A picnic seems just right. A barbecue even better. A barbecue with Doc Watson , almost irresistible.