By Bob Hicks

Geishas, kabuki actors, mountain landscapes, samurai scenes.

Check, check, check, check.

But what about those spine-tingling scenes of natural disaster?

The Portland Art Museum‘s collection of Japanese woodblock prints has long been a strong suit in its permanent collections, and the new exhibition The Artist’s Touch, the Craftsman’s Hand, which features about 230 prints from a collection of more than 2,500 covering the past 340 years, is a welcome and major summation of the museum’s holdings in this fascinating limb on the great tree of art. I wrote about the show in Friday’s A&E section of The Oregonian.

The Portland Art Museum‘s collection of Japanese woodblock prints has long been a strong suit in its permanent collections, and the new exhibition The Artist’s Touch, the Craftsman’s Hand, which features about 230 prints from a collection of more than 2,500 covering the past 340 years, is a welcome and major summation of the museum’s holdings in this fascinating limb on the great tree of art. I wrote about the show in Friday’s A&E section of The Oregonian.

To call that story a review is a bit of a stretch. The exhibition is far too complex to be broken down adequately in a newspaper-length piece, and I’m happy to leave the tough critical analysis to the historians and art academicians who know the territory far better than I do. What I tried to do was simply provide a cultural context for the artwork and a frame for viewing it.

In my piece for The Oregonian I concentrated on the prints’ role in fostering a sense of stability — perhaps even an illusion of stability — in the Japanese culture that the artists reflected in their works. As a generalization, that’s true.

But there are several intriguing side stories to this exhibit.

One is the undercurrent of sensuality, sometimes breaking out into outright eroticism. It’s a major theme in Japanese art, and actually underplayed in the Portland collection, but here and there it does show its head (along with other parts of the anatomy). The exhibit lacks the beautifully explicit shunga prints picturing copulation but has a few examples of the frisky but merely teasing abuna-e prints, which are in roughly the same family as American pin-ups. One, Ishikawa Toyonobu’s Woman with a Fan: Calendar Print for 1766, is a sister in spirit to a Marilyn Monroe centerfold or a Rita Hayworth calendar photo, the kind you used to see hanging on the walls of garages when gas stations still had mechanics and were called, with some justification, service stations.

My A&E story also emphasized the domestic nature of the prints, and as a generalization that’s true, too. But there are also exceptions here. One is several semi-propagandistic war scenes (often in triptychs, to give a Cinemascopic perspective) that reflect the nation’s expansionist and defensive positions on the international scene. What’s interesting is that for all the glorification of battle and reflections on the heavy toll of war, the artists still look on these prints as objects of aesthetic pleasure: We’re meant to admire the skill, imagination, and craftsmanship that went into creating the images.

And a portfolio of 36 prints by a half-dozen artists illustrating the aftermath of the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923 is an eye-opener. (All of the prints were carved by Nagashima Kiichi, printed by Tamura Tetsunosuke and published by Hoshino Seki.) The quake, registering 7.9 on the Richter scale, struck at 11:58 a.m. on September 1, with its epicenter in Sagumi Bay, about 50 miles southwest of Tokyo. Fires swept through Tokyo and Yokohama. An estimated 140,000 people died, and nearly 700,000 were left homeless. As the museum’s Asian art curator, Maribeth Graybill, notes in the exhibition catalog, “Many artists, keenly aware that they were witnesses to an event of epochal significance, spent days and weeks traversing the city and outlying districts, filling sketchbooks with firsthand impressions of the disaster.”

The resulting woodblock prints echo the formalist beauty of the Japanese printmaking tradition, but literally with a twist: Tradition, like the nation itself, has been shaken up. The images have a transitory freshness, a sense of the reportorial you-are-there. The artist Tekiho’s The Unscathed Kannon Hall of Yakenokoritaru Asakusa Temple shows the mist-enshrouded temple building indeed unscathed in the background — and in the foreground a tangle of livewire downed power lines and leaning power poles. The same artist pictures the fiercely rising plumes of The National Sumo Arena in Flames, and Taisho Janinen Kugatsu has an even more tense and twisted image of fiery destruction, Matsuchiyama, depicting the ruins of the grounds near a temple. Several prints show the human victims, standing forlornly on street corners, lining up for rice rations, at first aid stations. One shows a dog sniffing at the ground amid the rubble. Kancho Utsusu’s almost hallucinatory depiction of a twisted bridge and tilted house along the Katase River in the suburban Kugenuma District is a vision of tradition literally uprooted.

It all seems familiar in light of this year’s triple whammy of earthquake, tsunami and nuclear meltdown in northern Japan. In an odd way, these prints from the 1920s also seem to mark a more fundamental fissure — the final reckoning between the feudal and modern worlds. From this point, there is no going back. Industrialization, war, defeat, social upheaval, rebuilding, internationalism and the future lie ahead. The floating world is over. The age of sink or swim has begun.

It’s a brave, if jittery, new world. And after Japan’s defeat in World War II it’s a new world of art, too. The exhibition’s final section, of prints made after 1945, reflects the fearsome and emphatic triumph of the new. We haven’t even begun to talk about that.

*

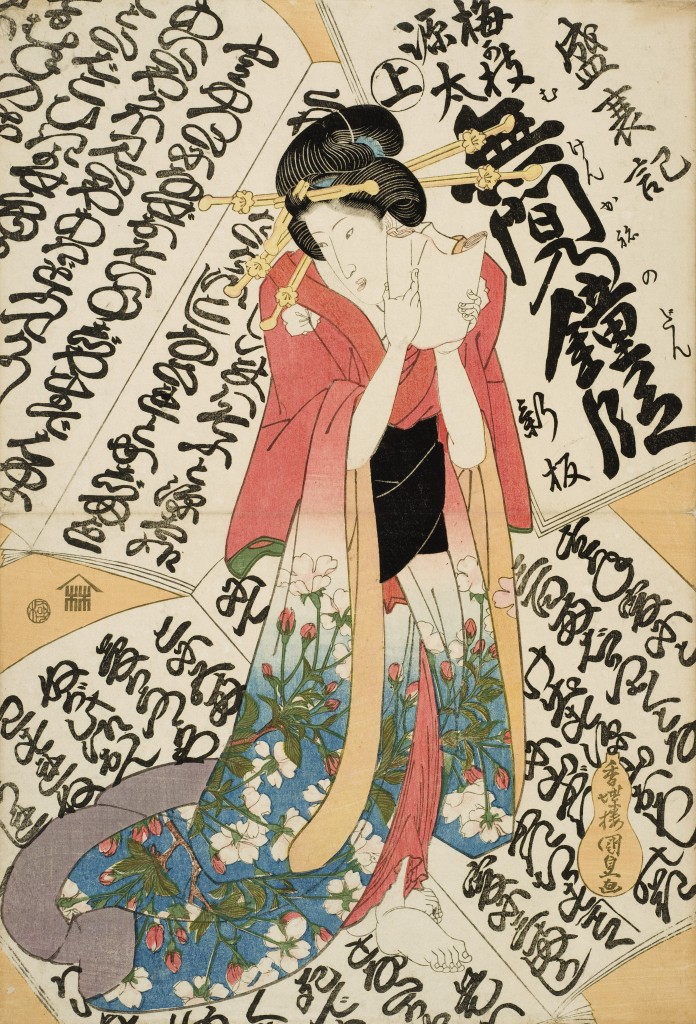

ILLUSTRATION: Utagawa Kunisada, “Young woman surrounded by the text of a libretto,” c. 1832, Portland Art Museum/The Mary Andrews Ladd Collection.