By Bob Hicks

Twenty-six years after she first impersonated the fabulous Sophie Tucker onstage, the big-talented Portland singer and comedian Wendy Westerwelle’s return to Soph: An Evening with the Last of the Red-Hot Mamas is a revival in more than one way. It marks Westerwelle’s own continuing return to the spotlight following her bravura turn earlier this year in Martin Sherman‘s one-woman play Rose (which I wrote about here and here) as well as a revival of interest in Tucker, a giant of 20th century American entertainment who has been lamentably overlooked in the years since her death in 1966. (She was born in 1886 in the Ukraine but arrived soon after in Hartford, Connecticut, where her family went into the restaurant business and young Sophie began singing for tips.)

You can catch up with my review of Soph for The Oregonian here, then stick around for a ramble through the pop-history parade. Westerwelle’s performance has got me to thinking about yet another revival of sorts, a historical reminder of the changing cavalcade of American popular culture and the important if sometimes embarrassing spectacle of facing up to what we’ve been as a nation and what it means to what we are now.

Soph is primarily a celebration of Tucker’s bawdy wit and rollicking style; Westerwelle isn’t looking to uncover any demons or wag her finger at the occasional ruthlessness that Tucker employed in pursuit of her career. But to Westerwelle’s credit, and to the credit of director Don Horn, who had a big hand in reshaping the script, neither does she shy from a few uncomfortable facts, such as Tucker’s vaudeville beginnings performing “coon songs” in blackface. It was a standard format in vaudeville, the grinning minstrelsy and exaggerated drawls of the happy watermelon-loving “colored folk” as performed by white (and sometimes black) entertainers.

Soph is primarily a celebration of Tucker’s bawdy wit and rollicking style; Westerwelle isn’t looking to uncover any demons or wag her finger at the occasional ruthlessness that Tucker employed in pursuit of her career. But to Westerwelle’s credit, and to the credit of director Don Horn, who had a big hand in reshaping the script, neither does she shy from a few uncomfortable facts, such as Tucker’s vaudeville beginnings performing “coon songs” in blackface. It was a standard format in vaudeville, the grinning minstrelsy and exaggerated drawls of the happy watermelon-loving “colored folk” as performed by white (and sometimes black) entertainers.

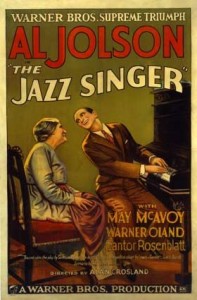

Coon songs spawned a protean offspring that has stayed in American pop and musical culture, sometimes explicitly and sometimes subversively: one way to look at the ruder extremes of gangster rap is as an ironic reaction to the fears, stereotypes and put-downs of coon songs, which were every bit as popular, sometimes selling in the millions of copies. Al Jolson famously got down on his knees and belted out the coon tradition in the first full-length talkie movie, The Jazz Singer. Amos ‘n’ Andy kept it going for decades on the radio and television. It weighs, probably unfairly, on the reputations of great artists such as Louis Armstrong and Cab Calloway, whose eagerness to entertain is criticized in some circles as Uncle Tomism. (Terry Teachout’s new biography Pops argues vigorously against the charge in Satch’s case, and anyone who’s ever listened to Armstrong’s radical recordings from the 1920s with his Hot Five and Hot Seven knows better, anyway.) The tradition crops up at the oddest and most casual moments in old movies such as the otherwise innocuous 1948 Cary Grant comedy Mr. Blandings Builds His Dream House, in which a residual Mammy character (she’s the family maid) saves the day by coming up with a down-home slogan for a new ham product. Black artists from Robert Colescott to Kara Walker and Portland’s Arvie Smith have satirized the minstrelsy tradition. So have actors such as Godfrey Cambridge in the Melvin Van Peebles movie Watermelon Man, and Eddie Murphy in the likes of Trading Places and the Beverly Hills Cop movies.

We’ve been down this street before, with arguments about how Shylock should be portrayed in The Merchant of Venice, and even whether the play should be performed at all. And of course there have been many arguments over Mark Twain’s use of the name “Nigger Jim” in The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, and whether the appellation doesn’t disqualify from the canon the book that many critics have called the greatest novel ever written by an American. The issues aren’t easy, and while it’s a good thing to face such things squarely as part and parcel of our collective past, it’s also easy to understand the fear and loathing that such references incite. In a way our cultural willingness to face the fears of the past has played a key role in the congressional battle over repealing “don’t ask don’t tell,” a cultural anachronism (it’s easy to forget that it was actually a step forward in its time) that seems finally on its way out the door despite the doomsayings of Sen. John McCain and the usual on-air natterers.

Making Tucker’s performances in blackface more interesting historically and personally is the fact that she was Jewish, and made no bones about it, and undoubtedly faced roadblocks of her own in the entertainment business because of it. The Holocaust was still in the future, but the makings of it were all around, plain to see for anyone on the outside looking in. Still, show business had rules, and if you wanted to succeed in it, you had to pay attention to them: You want a spot in the show, young lady? Sure. Put on some cork. Here’s your lyrics. If you were ambitious, you tended to bide your time until you could set your own rules.

Tucker was extraordinarily ambitious, and she knew how the business worked. Though it’s not in the current slimmed-down version of Soph, her advice to the young Oregon crooner Johnnie Rae (Cry) is locally famous: “If you want to make it in show business, kid, get the hell out of Portland.” Yet surely it meant something that when Tucker sang in blackface she tried to do it “right”: She was known for studying voice and performance with black performers and hiring black composers and musicians at a time when doing so wasn’t easy. And it’s true that she abandoned blackface as soon as she felt she could. She claimed that producers funneled her toward minstrelsy because she was too fat and plain-looking for friskier roles. The joke is that, like Mae West, she became famous for her sexual playfulness and bawdy patter.

A lot of people have argued that America is more Rome than Greece. We’re a country of pragmatists, not artists; of engineers, not philosophers. We live by the rules of expediency. Of course, that’s an overstatement: the reality is far more complex. But expediency is important. To reach an objective, we do what it seems we need to do when we need to do it. It’s as true in our popular culture as in our intellectual, political and social cultures. For a variety of reasons, mostly having to do with the subterranean fears and resentments of our great racial divides (and if you think they’re history, just scan through the comment posts on the Web sites of The Oregonian and almost every other American newspaper) coon songs were written and performed because they had a huge and appreciative audience. They were money in the bank — so much so that some of the most popular coon songs were written by black lyricists and composers, who knew their market and gave it what it wanted.

Was Sophie Tucker wrong to perform in blackface? No doubt. At an important level, any perpetuation of a bad tradition is a capitulation. We continue to fight in Afghanistan and Iraq because, well, that’s the way things are: who are we to change the way of things? But advancement rarely comes prettily. Good emerges from bad. Few performers actually enjoyed doing blackface. “That day has passed with the softly flowing tide of revelations,” the African American composer Bob Cole, author of the popular 1898 comedy A Trip to Coontown, later remarked. By acknowledging the worser part of ambition in Tucker’s life, Westerwelle and Horn have done Sophie, and American history, right. It’s pragmatic. What happened, happened. It’s part of the story, and not the whole story. Remember the past, but don’t get stuck in it. Think about it, learn from it, be humbled by it, be aware of its ghosts. And move on. Who knows? Maybe someday people will scratch their heads the way we do now about the very idea of coon songs and say, incredulously, “You mean, there was a time when gay couples couldn’t get married?”

*

PICTURED: Wendy Westerwelle as Sophie Tucker in “Soph: An Evening with the Last of the Red-Hot Mamas.” Photo: Triangle Productions/John Rudoff.