Writing is the act of accepting the huge shortfall

between the story in the mind and what hits the page.

– Richard Powers

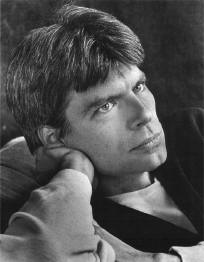

Richard Powers did not disappoint the small but very attentive group at his reading March 6. We accept on faith, I suppose, his claim that there is a shortfall between what is in his mind and what shows on his page, but we’ll never detect it, because what he writes is such a seamless weaving of disparate threads, as in the story he read that night. Called “Modulation,” and written special for his reading tour, it interweaves the stories of four people in places as various as Iraq, Sydney, Germany and an “I” state campus in the dead of winter. Different temperaments, different relations to music, but each trying to detect a secret harmony, a ghost tune they strain to hear in the global jangle of music, samplings and crossover genres, bootlegs and illegal downloads. Music – “the art that leaves nothing,” except the desire to read “Modulations” when it is published this spring in Conjunctions 50, a special anniversary collection of stories and poems by 50 writers.

Richard Powers did not disappoint the small but very attentive group at his reading March 6. We accept on faith, I suppose, his claim that there is a shortfall between what is in his mind and what shows on his page, but we’ll never detect it, because what he writes is such a seamless weaving of disparate threads, as in the story he read that night. Called “Modulation,” and written special for his reading tour, it interweaves the stories of four people in places as various as Iraq, Sydney, Germany and an “I” state campus in the dead of winter. Different temperaments, different relations to music, but each trying to detect a secret harmony, a ghost tune they strain to hear in the global jangle of music, samplings and crossover genres, bootlegs and illegal downloads. Music – “the art that leaves nothing,” except the desire to read “Modulations” when it is published this spring in Conjunctions 50, a special anniversary collection of stories and poems by 50 writers.

Powers explored the theme later in response to a question about the fate of music, or any other “intimate art” such as reading, “in an age of technological ubiquity,” as he phrased it. He’s not worried. Every age, he believes, has produced a music “surprising for its moment.” Being grounded in our “now” is second nature in his novels.

In my preview post on February 29, I said Powers is a real test for readers in this day and age, and noted that while his novels aren’t especially difficult, they are long and they do make you think. I considered again why I feel that way as I sat in the museum audience. A good part of the group appeared to be a decade or more older than Powers. These are old school readers who like the feel and heft of a book and are willing to dig in and stay the course when it leads somewhere other than a dead end. We were like older brothers and sisters proud of the younger sibling, or parents, proud of our kid, or proud that our kid knows the brightest kid in school, or just proud to know that someone that bright writes these books just for us. We were there in the wonderment at the heart of the best question all night: “How do you put it all together?”

Powers said that his writing process is top down and bottom up. From the top he starts with an elaborate outline interrelating themes and characters. But writing from the bottom, characters and events surprise, raising themes of their own, changing the arc of themes, relations of characters, and workings of plot. And then he quoted lines from Theodore Roethke’s poem, “The Waking”:

I wake to sleep, and take my waking slow.

I learn by going where I have to go.

That’s a great image for what happens in a Powers story. His novels address difficult subjects or provocative issues. In The Gold Bug Variations it is molecular biology and the music of Bach. In Galatea 2.2 it is computers and literature. In Plowing the Dark it is virtual reality and the politics of terrorism and hostagetaking. In The Time of Our Singing it is music again, as well as Strom’s scientific theories of time and the history of the American Civil Rights movement. But Powers’ learning never reads like “research.†In The Echo Maker, Capgras Syndrome, the brain disorder that makes the main character believe his sister is an imposter, becomes a metaphor for echoing themes about recognition and estrangement, including human estrangement from the natural world. Powers’ learning is just second nature, often reflected in the perfect metaphor, as in this description of a duet from The Time of Our Singing:

The tune is propelled by the simplest trick: Stable do comes in on an unstable upbeat, while the downbeat squids away on the scale’s unstable re. With this slight push, the song stumbles forward until it climbs up into itself from below, tag-team wrestling with its own double. Then, in scripted improvisation, the two sprung lines duck down the same inevitable, surprise path, mottled with minor patches and sudden bright light. The entwined lines outgrow their bounds, spilling over into their successors, joy on the loose, ingenuity reaching anywhere it needs to go.

Even if you don’t know the music, you follow the sense, in this case an allusion to the interracial marriage at the heart of the story.

But beyond Powers’ command of scientific knowledge, there is an ethical dimension in science and technology that plays out in his stories. Powers writes from the point of view, not of the Luddite, but of one who appreciates what technological advances have given us in our estimation of the world, but wonders how we bridge the gap between knowledge and responsibility. As he wrote in a 1999 essay about millennium science, “Eyes Wide Open,” “our vast increase in technical ability has not been accompanied by commensurate increase in our social or ethical maturity.” Powers says he’s not interested in explaining the science so much as in exploring the symbiotic relation between science and art, the “behind-the-scenes” humanness of scientists and what they do.

Powers is brilliant. There’s genius that bristles, mostly because it is a narrow genius and is wary, uncomfortable out of its range. And there’s genius unassuming. Unassuming, because it knows everything, with no need to bristle. Powers is the latter, I think. But to say his novels are not difficult may be misleading. Powers weaves genetic science, computer technology, neurology, photography, musicology, history and all else into the fiber of his stories, and even if I don’t understand the concepts, I never feel I lose the thread of the story.

Think about the difference between James Joyce and Thomas Mann. Modern sensibilities, but different ways of engaging the world. You have the sense Powers knows and appreciates a writer like Thomas Pynchon, full of odd tangents and willful obscurities, at play in the minefield that is modern life. But Powers’ sensibility, steeped in the modern and the postmodern, writes like an old-fashioned realist. Think of Dreiser and Norris taking on THE subjects of their day, but with the skill and sensitivity of William Dean Howells or Edith Wharton, approaching the moral and ethical complexity of Henry James. If you still reach for these writers now and then, you will find pleasure in Powers’ novels, too.

Powers said his immediate project involves having his genome sequence mapped so he can write an article about what is found there. Asked if he’s concerned about finding something in the evolutionary lineage or individual code, such as the sign of some future ailment waiting to be triggered, he responded something to the effect that he’s curious about being able to weigh the value of some piece of knowledge without being able to do anything about it. Sounds like the heart of a new novel, and echoes something Powers said earlier in the evening, quoting Peter Brook, about how we read “in anticipation of retrospection.”