Writing is the act of accepting the huge shortfall

between the story in the mind and what hits the page.

– Richard Powers

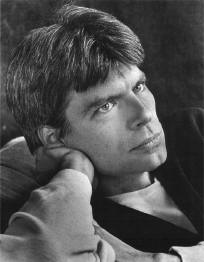

Richard Powers is a real test for readers in this day and age. His novels aren’t especially difficult but they are long and they do make you think. And once you taste the waters of any of his nine you’ll want to drink them all in. I’m still captivated by the cover of his first, Three Farmers on Their Way to a Dance, with its photograph by August Sander that forms the basis for the interrelated stories of three Dutch and German stepbrothers on the eve of World War I, a computer techie in contemporary Boston, and the narrator P., who discovers the photo in a Detroit museum and brings it to life with research and imaginative musings. The novel tells the story of photography and how it has documented the brutalities of the twentieth century in a way that makes previous centuries’ horrors we only read about a little less real. But Three Farmers on Their Way to a Dance is also a very personal and affecting story.

Richard Powers is a real test for readers in this day and age. His novels aren’t especially difficult but they are long and they do make you think. And once you taste the waters of any of his nine you’ll want to drink them all in. I’m still captivated by the cover of his first, Three Farmers on Their Way to a Dance, with its photograph by August Sander that forms the basis for the interrelated stories of three Dutch and German stepbrothers on the eve of World War I, a computer techie in contemporary Boston, and the narrator P., who discovers the photo in a Detroit museum and brings it to life with research and imaginative musings. The novel tells the story of photography and how it has documented the brutalities of the twentieth century in a way that makes previous centuries’ horrors we only read about a little less real. But Three Farmers on Their Way to a Dance is also a very personal and affecting story.

Powers’ background in physics, computer programming, music and English studies finds its way into his novels in very intellectual and sophisticated forms. He is one of the smartest writers I’ve ever read, but it is the emotional core of his novels that is so amazing. I wouldn’t miss his appearance at the Literary Arts special event, Thursday, March 6, at 7:30; Portland Art Museum Fields Sunken Ballroom, 1119 S.W. Park Ave. Tickets are $15.00: www.pam.orgor 503-226-0973.

I hardly know where to begin. Plowing the Dark will resonate with Pacific Northwesterners. It involves alternate stories about a Seattle woman working on a virtual reality project, including a version of van Gogh’s Bedroom at Arles, and a young American teacher held hostage in Beirut, whose only escape is through the virtual reality of his imagination. It’s also a neat love story. So is Galatea 2.2, Powers’ fifth and shortest novel, about a writer named “Richard Powers,” who tries to teach a computer to appreciate literature (the Pygmalion story) and recalls the circumstance of writing his four novels, all of which resemble the real Powers’ books. Galatea 2.2 is a good way to catch up with, or catch onto, this wonderful writer.

A different kind of love story, The Time of Our Singing, interweaves the saga of a biracial family with the history of America during the crucial years of the civil rights era. The Stroms (as ironic as that name might be) have three children who react in different ways to their biracial status. Forces threaten to pull them apart, but pride in their parents’ relationship holds them together. They wonder how their parents could marry and raise mixed-race children, and seem so oblivious to racism. Their parents’ answer is very willful: they wanted their children to live, not black, not white, but “beyond race.†A romantic view, but there is a romantic element in all Powers’ novels that shines through their cerebral quality.

Powers’ stories blend narrative realism with a structured complexity that reflects his admiration for literary modernists like Joyce and Proust, along with some of the imagination-stretching playfulness of Pynchon. But most of all I remember, novel to novel, gripping personal stories of family relationships, illness, love and love lost or love not quite reachable. (I’d declare they’re sentimental, i.e., they make me weep, but that seems too much to try to explain just now.) No more gripping than in his ninth novel, The Echo Maker, which won him the National Book Award last year. It’s the story of a young man named Mark, injured in a truck accident, and his sister Karin, who quits her job to take care of him. Mark awakens with Capgras Syndrome, a delusion that his sister is an imposter and that his familiar world has been recreated by agents of a power out to get him. His paranoia leads those around him to question their own pasts and the nature of the world we inhabit at the beginning of the new millennium.

The story is set on the Platte River in Nebraska, with the annual return of the ancient-looking and endangered sandhill cranes as backdrop. I grew up a couple hundred miles north of there in South Dakota, and I know what he means when he says there’s something “utterly featureless†about that stretch of America from South Dakota to Oklahoma. Ole Rolvaag documented the lives of nineteenth century Dakota immigrants in Giants in the Earth, a novel suffused with the loneliness of that immense and estrangement-inducing space. A space, not as empty of things as it was then, but still lonely. It’s a natural place for The Echo Maker, a stark mystery of human memory and something of an environmental mystery, too. And there’s an immense sadness powering the story as well. The sadness of the thought that we are aliens in a world that on occasion seems like the right and likely place for us to be. The sadness of the thought that we may never get the story right.

I’m curious what Powers will say in person, if we’ll recognize the romantic storyteller buried behind all those words.