By Bob Hicks

The new baby arrived the other day, and it’s a whopper: 12.2 inches long, 10.3 inches across, almost 2 inches thick and 8.5 pounds. It came after a labor so long you don’t want to contemplate it, but when it finally arrived it came out handsome and beautifully illustrated.

The new baby arrived the other day, and it’s a whopper: 12.2 inches long, 10.3 inches across, almost 2 inches thick and 8.5 pounds. It came after a labor so long you don’t want to contemplate it, but when it finally arrived it came out handsome and beautifully illustrated.

Coffee tables across America have been put on alert: Brace yourselves. The new kid’s big.

Beth Van Hoesen: Catalogue Raisonné of Limited-Edition Prints, Books, and Portfolios has just been published by Hudson Hills Press, in association with the Oakland Museum of California, Racine Art Museum in Wisconsin, and the University Museums, Iowa State University, Ames.

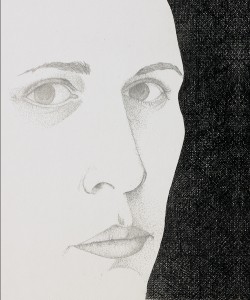

Van Hoesen, who died late last year at age 84, was a longtime San Francisco artist who specialized in printmaking, taking as her subject the small things of life: animals, insects, flowers, babies, fruits and vegetables, dolls, portraits. She also drew and made prints of a lot of nudes — a portfolio of her male nudes was one of the first projects published by the Bay Area’s fabled Crown Press — and completed a little-known but highly intriguing series of portraits of people from the punk scene in San Francisco’s Castro District, near the old firehouse where Van Hoesen and her husband, the tapestry designer and watercolorist Mark Adams, lived and worked for close to 50 years. Physical veracity was extremely important to her, and in the best of her work that attention to truthfulness was much more than skin-deep.

I wrote what became the catalogue’s lead essay, Becoming Perfect, which is primarily about Van Hoesen’s drawings, both finished pieces and preparatory drawings for her hundreds of prints. In the end, her work is really about the magic of the line, and getting it right.

The idea of a catalogue raisonné is to publish illustrations and details on as many pieces of an artist’s work as you can get your hands on. In Van Hoesen’s case that’s an awful lot, and fresh pieces kept showing up during the course of work on the catalogue. Quite a few that I hadn’t seen before ended up in the book. If I’d seen some of them before I started writing I’d have paid more attention in my essay to her early drawings and prints, from the mid-1940s through the 1950s, when she was a student and soon after. They can be imitative and illustrative, as the works of young artists so often are, but they also had an easy, wryly funny charm and a quirky off-centered quality all their own. Later her work became both surer and more rigorously contained.

A project like this is both a scholarly undertaking and a picture-book. It’s important for a record to be made. It’s also pleasurable simply to look through the pictures, and from that vantage the words play definite second fiddle. The hard work on this project — work which other people did — was gathering and collating the artworks and digging out all the vital technical and historical detail on them. It was Anne Kohs’ energy, persistence and design that drove the project. The unsung hero is Diane Roby, who handled huge amounts of the research on the artwork and gave me good advice in the process. The book is distinguished by an excellent introduction by the erudite California artist, collector and writer Joseph Goldyne, who was also my co-author on another, much smaller, Van Hoesen catalogue, The Observant Eye, for the Fresno Art Museum, and who knows how to tell a good story over lunch. My thanks also to the deft and perceptive Michelle Piriano, my editor through most of the project, who taught me a good deal about writing for a specialized audience. And the catalogue was produced by Seattle’s excellent Marquand Books.

One of the great things about working on this project and another related to it is that it introduced me to a stimulating variety of California artists who provided the broad artistic milieu in which Van Hoesen flourished. Many of them I knew about, at least glancingly — people like Richard Diebenkorn, Frank Lobdell, Imogen Cunningham, David Park, Robert Arneson, Wayne Thiebaud, Roy DeForest. Others I came to know about and admire: Gordon Cook, Ruth Asawa, Joan Cook, Robert Bechtle, Nathan Oliveira, and three in particular who became both excellent sources and people I took an instant liking to: the painter and intaglio printer Timothy Berry, the talented and gregarious nonagenarian painter Theophilus Brown, and the photographer Diana Citret, who sometimes modeled for Van Hoesen and Adams’ weekly drawing group.

Big project, big baby: 592 oversized pages, 1,147 color plates, 8 black & white plates. It’s available through Powell’s, Amazon, Barnes & Noble and other outlets.