“By and large, time moves with merciful slowness in the old-fashioned world of writing. … (T)he rhythms of readers are leisurely. They spread recommendations by word of mouth and ‘get around’ to titles and authors years after making a mental note of them. … A movie has a few weeks to find an audience, and television flits by in an hour, but books physically endure, in public and private libraries, for generations.”

John Updike, The Writer in Winter

Collected in Higher Gossip: Essays and Criticism, 2011

By Bob Hicks

Mr. Scatter contends that time is not an arrow: we all live in several pasts, several presents, even a few futures. At any moment, and in separate yet overlapping ways, we are old and young, conservative and radical, classical and modernist. We are ever-shifting texture, contradictions that forge ahead and loop back on ourselves. Crusty old children. Impetuous adults. Civilized wild creatures. Logical irrationalists. Mysteries, even to ourselves.

In that sense reading and writing may be the most human of the arts. They follow us, and sometimes lead us, into these bewilderments of emotion and thought – the places that may not make sense, but simply are. Books explain things, and smudge them up. They are private pleasures that draw us beyond ourselves. And they are time-travelers. They can be “new” to any given reader at any given time, sometimes even when that reader has experienced them before. O miracle divine!

In that sense reading and writing may be the most human of the arts. They follow us, and sometimes lead us, into these bewilderments of emotion and thought – the places that may not make sense, but simply are. Books explain things, and smudge them up. They are private pleasures that draw us beyond ourselves. And they are time-travelers. They can be “new” to any given reader at any given time, sometimes even when that reader has experienced them before. O miracle divine!

This year, Updike’s notion of the “merciful slowness” of literature sets the table for my annual recap of my year’s readings. Considering the rivers of writing that flow into the great literary ocean in any given year, it’s a foolish quest. Yet I feel curiously compelled to undertake what amounts to a private reckoning in a public space. These books, all of which I read in 2011, engaged me. I believe in them, and like most readers in most times and places, I feel an urge to pass my enthusiasms on to someone else who might enjoy them just as much.

This is not a best-of-2011 listing. A few of the books were new last year. Several others have been kicking around for quite a while. In subject and style they sprawl all over the place, from classic animal fable to the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation to the wonders of the Louvre and the woes of Henry Miller and Anais Nin. That sort of leaping-about is the way life actually works for most of us, and it’s the way I like it. The discipline of writing opens up the world. And it isn’t simply, or even primarily, about what’s new, although a steady flow of fresh energy is necessary to its continuing health. How can we understand the new without some familiarity with the old? Why would we want to try?

Here are fifteen books, old and new, that for one good reason or another have stuck with me. I’m a little surprised to see no classics on the list, and shocked to realize that only one of the fifteen is by a woman writer. This seems both highly unusual and a little embarrassing: I resolve to cut back on the testosterone and get in better literary balance during 2012.

The Love Lives of the Artists: Five Stories of Creative Intimacy, Daniel Bullen. So you think Kim Kardashian’s got a complicated sex life? What about Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir? Or Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo? In this fascinating new series of linked profiles, Bullen looks at matters of sex and love through these two artistic couples and three others: Lou Andreas-Salome and Rainer Maria Rilke, Alfred Stieglitz and Georgia O’Keeffe, and Henry Miller and Anais Nin.

The Love Lives of the Artists: Five Stories of Creative Intimacy, Daniel Bullen. So you think Kim Kardashian’s got a complicated sex life? What about Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir? Or Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo? In this fascinating new series of linked profiles, Bullen looks at matters of sex and love through these two artistic couples and three others: Lou Andreas-Salome and Rainer Maria Rilke, Alfred Stieglitz and Georgia O’Keeffe, and Henry Miller and Anais Nin.

In addition to being artists, all of these couples were, well, more than couples. They lived together, and often apart, in open relationships of one sort or another. Some were married to third parties for economic or even emotional security. Some rode any hobby-horse that happened by. Some were serial monogamists, or even serial polygamists. Mentor/acolyte relationships were common: Andreas-Salome with the younger Rilke, for instance, and the established Stieglitz with the emerging O’Keeffe. Sometimes the sex cooled down but the emotional and intellectual bonds stayed strong. And often these lovers stressed the honesty and high-mindedness of their affairs while they were cheating (if the word meant anything in their lexicons) on others.

One of the things that Bullen explores is the role of intimacy in the artistic temperament. All ten of these people were adventurers in their personal lives as well as in their art; most declared that they were inhabiting brave new worlds. They were unquestionably exotic creatures. Andreas-Salome made herself conspicuously known to both Freud and Adler (and Nietzsche), and even took her own uncredentialed hand at psychoanalysis. Nin embarked on an incestuous affair with the concert-pianist father who had abandoned her many years earlier, while Miller, the celebrator of the widely sown seed, began to long for exclusivity. While most of the group shrank from the idea of children, who might have diverted their energy from their art and personal lives, Rivera dropped kids casually, like dumplings in a stew, and then pretty much ignored them. The idea of selfishness – that artists must be selfish, in service to their art – is central, even in these couples’ sometimes desperate mutuality: As Bullen writes, “There were moments when the artists could almost not endure their emotions, but the pressure to create – and to earn each other’s love by creating – was almost overwhelming.”

Bullen tells these stories with cool passion: Just the facts, ma’am, but the facts are plenty fascinating. The stories seem almost like extended written versions of First Encounters, Edward and Nancy Caldwell Sorel’s long-running series of vignettes in The Atlantic about famous people meeting famous people. Bullen concentrates on the aftermaths of those meetings, and the inspirations and wreckage that ensued. He reports scrupulously and writes well, and hints only briefly at his own feelings about his artists’ actions and moral decisions. As a result, he’s created a kind of moral mirror, allowing readers to see bits of themselves, or at least bits of their own attitudes, in what they read. Are these artists sacred monsters (as Bullen refers to Kahlo and Rivera), or simply monsters, or somehow sacred? Depends on how you view the glass. And while it’s true that everyone’s understanding of morality is different and different understandings can be equally valid, it’s also true that applying a rule of exceptionalism — artists simply live differently from other people — is a slippery slope. Moral exceptionalism seems rampant on Wall Street and in Washington, D.C., too. Still, Bullen’s artists are brilliant and undeniably different, and part of the fascination of their lives is of the train-wreck variety. I tend to think of them as purple cows: I’d rather see than be one.

Miss Lonelyhearts, Nathanael West. A rumbling freight train of comedy and horror: Young newshound with hopes and aspirations is stuck writing a lovelorn column and enters his own private hell. West mixed sex, religion and violence into an urban version of American Gothic in this 1933 novella, which I first read in my 20s in a $2.95 paperback version that also included West’s Hollywood Gothic The Day of the Locust. What Updike wrote about private libraries is true: Almost forty years later I picked the same paperback from my shelves and entered West’s astonishing world anew. Malcolm Cowley used the word “tenderness” to describe this savagely hilarious story of spiritual desperation. He was right.

The Louvre: All the Paintings, Erich Lessing and Vincent Pomarede. Note to tourists: It’s not all about Mona Lisa. My coffee-table book of the year, and it’s a good thing my coffee table has sturdy legs. This oversized book has 766 pages and includes images of 3,022 paintings, from Giotto to Goya with all the stops between. Many of the reproductions are thumbnails, but they’re all here – the entire painting collections of one of the world’s great museums – and the slipcovered volume includes a DVD-ROM that allows you to see any of the works as large as your computer screen will allow. For scholars and enthusiasts alike, a vital source of information and browsing pleasure. I’m looking right now at a piece I’ve never laid eyes on in the flesh, The Guitar Player Watched From Above, by an artist I don’t know, David Tenier the Younger, painted in about 1640, and it makes me think of another masterfully high-humored Lowlands painter of the Golden Age, Frans Hals. And so what if the painting’s almost four centuries old? Except for his costume, this roguish guitarist could be sitting in an industrial-eastside Portland bar, singing for his drinks. Paintings are time-travelers, too. The book isn’t just a pretty face, either. The commentaries are concise and illuminating.

The Louvre: All the Paintings, Erich Lessing and Vincent Pomarede. Note to tourists: It’s not all about Mona Lisa. My coffee-table book of the year, and it’s a good thing my coffee table has sturdy legs. This oversized book has 766 pages and includes images of 3,022 paintings, from Giotto to Goya with all the stops between. Many of the reproductions are thumbnails, but they’re all here – the entire painting collections of one of the world’s great museums – and the slipcovered volume includes a DVD-ROM that allows you to see any of the works as large as your computer screen will allow. For scholars and enthusiasts alike, a vital source of information and browsing pleasure. I’m looking right now at a piece I’ve never laid eyes on in the flesh, The Guitar Player Watched From Above, by an artist I don’t know, David Tenier the Younger, painted in about 1640, and it makes me think of another masterfully high-humored Lowlands painter of the Golden Age, Frans Hals. And so what if the painting’s almost four centuries old? Except for his costume, this roguish guitarist could be sitting in an industrial-eastside Portland bar, singing for his drinks. Paintings are time-travelers, too. The book isn’t just a pretty face, either. The commentaries are concise and illuminating.

An Object of Beauty, Steve Martin. With this fiercely funny novel of the New York art scene from the boom-boom eighties to the bust-bust aughts, Martin has taken on and possibly surpassed Woody Allen as our most literary American movie comedian. His tale of the rise and fall of the fiendishly attractive and grotesquely ambitious wheeler-dealer Lacey Yeager and her misadventures among the Old Masters and the New Marauders is more than just an insider’s keen dissection of the meeting-place of art and commerce. It’s also a lacerating look at the seductions and impulses of our late and partially lamented Gilded Age. Martin might have titled it What Makes Lacey Run? The best literary entertainment I read in 2011, with the bonuses of a gifted satirist’s edge and a likable humanist’s quality of mercy. Did you know that Maxfield Parrish and a larcenous soul can make you rich?

Daniel Martin, John Fowles. Another rediscovery from the private library. I read this long and complex novel when it came out in 1977, and last year finally read it again. It holds up well. Fowles’s hero may be a displaced Hollywood screenwriter from the ever-so-current seventies, but both he and his author seem to have nineteenth century turns of mind: There are bits of Hardy in the writing, and an old-fashioned sense that literature is more than a story; it’s also a philosophical reckoning. As in a Henry James novel, the writing can be knotty and a little exasperating, but you push through the thickets and discover long open meadows of reward. Daniel Martin is about romance and seduction and betrayal and discovering not just one’s own true core but also how to respect the unreachable core of someone you love – a much more difficult and humanizing achievement. Fowles is a little out of fashion these days. He’ll return.

The Most Beautiful House in the World, Wytold Rybczynski, and At Home: A Short History of Private Life, Bill Bryson. The trouble with too much writing about architecture is that it’s not really about buildings, it’s about sculpture. This is particularly true in architectural criticism, which tends to look at new buildings before they’ve actually been inhabited – before anyone’s had a chance to kick off their shoes, try the places on for size, lounge around a bit and see how they work on a daily basis. A house is not a home, and a building is not a work- or gathering-place. Rybczynski, with his 1989 account of how his desire to build a boat gradually morphed into the designing and construction of his family home, and Bryson, whose late 2010 historical ramble inspired by clues lent by the Victorian English country parsonage in which his family lived, approach the question of living spaces from the inside out. Rybczynski is the sanest and most elegant architectural writer I know of, a man who respects practicality, history, and above all, context (“I once saw a thatched cottage on a windswept slope in Carmel, California – it didn’t remind me of Devon but of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs”). Bryson is a born and practiced entertainer, with an open and curious mind — a mechanic of the intellect, fascinated by how common things work and the stories of how they came to be. At Home is a cultural history based on objects and spaces ordinarily taken for granted – the lives that time and human nature, more than artist/architects, have sculpted for us to inhabit.

The Scandalous Adventures of Reynard the Fox, Harry J. Owens, illustrated by Keith Ward. “The bitter enemies of Reynard the Fox held that he was a liar, thief, hypocrite, betrayer, outlaw, seducer, traitor, murderer; a red scourge, a galloping pestilence, a stench in the nostrils of all law-abiding citizens. Reynard replied that this was all a lot of bunk.” From Holiday Press in Chicago, the 1949 gift edition of this “modern American version” of the tales of the scalawag European trickster fox, whose exploits are so old that Chaucer borrowed from the stories in The Canterbury Tales. It’s a vigorously retold and beautifully printed edition, with sly illustrations by Keith Ward, and a lovely tale of unburied treasure to go with it: Mrs. Scatter discovered this copy for $19.95 (original penciled-in price $65) during a ramble through the shelves at Powell’s City of Books. And folded inside was a typed letter from author Owens, dated May 2, 1945 from Flossmoor, Illinois and addressed to “Dear Burton,” that reads in part: “We all regret that the limited edition has been delayed beyond the trade edition, but I guess it couldn’t be helped. Jerry Stepanek says if Burt Barr had been here to keep after the goddam thing, the suchavitch woulda been out a hell of a long time before this, war or no goddam war.” Here’s to brick-and-mortar bookstores. You won’t find that sort of thing on your Kindle.

The Scandalous Adventures of Reynard the Fox, Harry J. Owens, illustrated by Keith Ward. “The bitter enemies of Reynard the Fox held that he was a liar, thief, hypocrite, betrayer, outlaw, seducer, traitor, murderer; a red scourge, a galloping pestilence, a stench in the nostrils of all law-abiding citizens. Reynard replied that this was all a lot of bunk.” From Holiday Press in Chicago, the 1949 gift edition of this “modern American version” of the tales of the scalawag European trickster fox, whose exploits are so old that Chaucer borrowed from the stories in The Canterbury Tales. It’s a vigorously retold and beautifully printed edition, with sly illustrations by Keith Ward, and a lovely tale of unburied treasure to go with it: Mrs. Scatter discovered this copy for $19.95 (original penciled-in price $65) during a ramble through the shelves at Powell’s City of Books. And folded inside was a typed letter from author Owens, dated May 2, 1945 from Flossmoor, Illinois and addressed to “Dear Burton,” that reads in part: “We all regret that the limited edition has been delayed beyond the trade edition, but I guess it couldn’t be helped. Jerry Stepanek says if Burt Barr had been here to keep after the goddam thing, the suchavitch woulda been out a hell of a long time before this, war or no goddam war.” Here’s to brick-and-mortar bookstores. You won’t find that sort of thing on your Kindle.

The Ingram Interview, K.B. Dixon. Portland novelist Dixon is a happy contradiction, a cool miniaturist in a city of feverish literary expressionists. It’d be intriguing to see his rough drafts, because nothing’s rough in the finished manuscripts, which reveal a diamond-cutter’s precision. Dixon’s novels are made up of quick clipped scenes, usually interior monologues, that suggest a dry detachment even if the narrator is embroiled in an ungodly personal mess. The Ingram Interview, published in 2011, is written as a series of brief answers to questions posed by an unnamed interviewer to a retired English prof who’s been, in the cover copy’s words, “kicked out of an assisted-care facility because he was depressing the other residents.” And that’s not the half of it. You can read a Dixon novel and wonder if there’s anything to it at all. Yet there it sticks, stubbornly and almost mockingly, in your mind. I wrote about The Ingram Interview here.

On the Rez, Ian Frazier. The further adventures of confessed Indian wannabe Frazier and his Oglala Sioux buddy Le War Lance, following 1989’s Great Plains. In 2000’s On the Rez, Frazier explores the poverty and politics of the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation with clear-eyed sensitivity. Included is the tale of SuAnne Big Crow, a high-school basketball star and cultural heroine who was killed in a car wreck in 1992. Frazier intersperses a lot of history of broken promises and cultural thefts with his portrait of a place that, in spite of its extreme poverty, supports an enduring and evolving culture. This is, in interesting ways, the real “real America.”

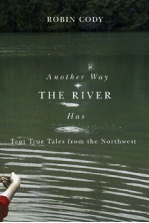

Another Way the River Has: Taut True Tales from the Northwest, Robin Cody. This recent collection of short pieces by the Portland novelist (Ricochet River), essayist and chronicler of place is part journalism, part memoir, and entirely a loving if open-eyed portrait of the Northwest lands and waters that have shaped him. “The River” is actually two rivers: the Clackamas, which runs through the timber town of Estacada, where he grew up; and the Columbia, the mighty highway that begins in the high wilds of Canada and tumbles with a ravenous swirl into the Pacific at Astoria. In The Turtle, a clunky old craft that falls into his hands, Cody explores the byways and eddies of the Lower Columbia, dropping in for a baseball game in Clatskanie or a getaway called Sand Island off of St. Helens. To make ends meet, and to learn a few things, he drives a schoolbus on a route for special-ed kids and referees basketball games involving a team of deaf players. He ambles out to the desert for the Pendleton Round-Up and thinks about the mysteries of the steelhead. All the while, he seems to be saying, “Look at the land and the water! This is what’s real! This is where you live!”

Another Way the River Has: Taut True Tales from the Northwest, Robin Cody. This recent collection of short pieces by the Portland novelist (Ricochet River), essayist and chronicler of place is part journalism, part memoir, and entirely a loving if open-eyed portrait of the Northwest lands and waters that have shaped him. “The River” is actually two rivers: the Clackamas, which runs through the timber town of Estacada, where he grew up; and the Columbia, the mighty highway that begins in the high wilds of Canada and tumbles with a ravenous swirl into the Pacific at Astoria. In The Turtle, a clunky old craft that falls into his hands, Cody explores the byways and eddies of the Lower Columbia, dropping in for a baseball game in Clatskanie or a getaway called Sand Island off of St. Helens. To make ends meet, and to learn a few things, he drives a schoolbus on a route for special-ed kids and referees basketball games involving a team of deaf players. He ambles out to the desert for the Pendleton Round-Up and thinks about the mysteries of the steelhead. All the while, he seems to be saying, “Look at the land and the water! This is what’s real! This is where you live!”

Irons in the Fire, John McPhee. Tough to let any year slide by without reading something by McPhee, one of the most consistently engaging reporters of our time. In 2011 it was this collection of essays from 1997, ranging from cattle-rustling in Nevada to geological criminology to an auction of exotic cars and the curious case of an undersized boulder with an oversized public profile, Plymouth Rock. McPhee has the gift of making you interested in anything that interests him, and over the years that’s covered a plentiful lot.

In My Old Age, Charles Deemer. The Portland playwright/novelist/screenwriter put out a slim volume of poems last year, each dealing in a stripped-down and vital way with the realities, diminishments and occasional rewards of growing old. Age, Deemer has discovered in his 70s, is a biological reality and a spiritual trick. One can be, and often is, 73 and 37 and 17 all at the same time. It’s keeping straight which is still capable of what that’s the problem. I wrote about In My Old Age here.

Second Fiddle, Rosanne Parry. Another Portland area novelist, Parry specializes in books for young readers, and as is so often the case, the matter of age is often almost incidental. Parry has a way of getting inside the minds and emotions of kids in a way that reminds you that childhood is a complex moral and intellectual country, often not all that different from adulthood except in experience. This one’s set in Europe in the waning days of the Cold War and involves a trio of teen-aged Army brats who also make up a chamber-musical group and, after rescuing an almost-dead Estonian soldier in the Russian army shortly after the fall of the Berlin Wall, take off on a secretive journey to Paris that involves them in all sorts of political and personal adventures. I wrote about Second Fiddle here.

Just Food, James E. McWilliams. You can disagree with a lot of things in this book about food systems and the problems of feeding the world as it faces an unprecedented population explosion. The book exudes a certain Malthusian alarmism, and some of McWilliams’ critics have accused him of shilling for the chemical companies. Certainly McWilliams, who is personally vegan although he promotes the cultivation of seafood as an efficient way to feed a lot of people, deliberately pushes his arguments to extremes. Yet he also says some interesting things that need to be said. Sometimes local isn’t better than global: efficiencies of scale and transportation can make the environmental costs of agribusiness cheaper than less efficient local organic farming. Organic isn’t always better than conventional: because of lower yields, it requires more acreage to create the same amount of crops and so can eat up land that might otherwise remain undeveloped. Chemical farming did help save millions or even billions from starvation during the Green Revolution, and still has a role to play in the feeding of future billions. Science is not necessarily the enemy. Genetically modified food isn’t automatically evil, and if employed carefully might create a lot of good. Food purity is becoming a religion, and like all religions it discourages a careful analysis of the facts. The answers aren’t easy – and if Just Food gets that essential point across to a sometimes self-satisfied foodie world that thinks it can have its cake and eat it, too, it’s done a good thing.

*

This is a good place to mention also that the art book Beth Van Hoesen: Catalogue Raisonné of Limited-Edition Prints, Books, and Portfolios was published in 2011 by Hudson Hills Press. I wrote the lead essay for the catalogue, and wrote about the process for Art Scatter here.

This is a good place to mention also that the art book Beth Van Hoesen: Catalogue Raisonné of Limited-Edition Prints, Books, and Portfolios was published in 2011 by Hudson Hills Press. I wrote the lead essay for the catalogue, and wrote about the process for Art Scatter here.

While we’re on the subject, here are our reading reports for those antiquated years, 2010 and 2009:

ILLUSTRATION, top right: Jean-Honore Fragonard, “The Reader,” ca. 1770-72. National Gallery of Art/Wikimedia Commons

Pingback: K. B. Dixon's book The Ingram Interview is reviewed by critic extraordinaire Bob Hicks on ArtScatter.com - Inkwater()