“It is never entirely safe to laugh at the metaphysics of the man-in-the-street.”

— J.W. Dunne, An Experiment With Time

I’ve spent three weeks in a state of distraction. Ten minutes here and there, cracks in time, I browsed the summer fiction issue of The New Yorker (June 9 & 16, 2008). I found several scattered signs of our times.

1. Peter Schjeldahl on a Jeff Koons retrospective at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago. Koons is a “major artist,†one of those who can “X-ray the cultures that give rise to them,†Schjeldahl begins portentously. But the culture that gives this particular rise is one in which “intelligence is obsolete.†Koons’ iconic “product line†sculptures–the latest of which, a huge steel heart, looks “incredibly costly†and “as sweet as dime-store perfume‖are turned out in a factory employing some 90 assistants. (“Rabbit,” shown here, is a stainless-steel cast of an inflatable bunny.) The steel heart, chirps Schjeldahl, “apostrophizes our present era of plutocratic democracy, sinking scads of money in a gesture of solidarity with lower-class taste.†And that major artist, X-ray vision-ness? “We might wish for a better artist to manifest our time, but that would probably amount to wanting a better time.â€

1. Peter Schjeldahl on a Jeff Koons retrospective at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago. Koons is a “major artist,†one of those who can “X-ray the cultures that give rise to them,†Schjeldahl begins portentously. But the culture that gives this particular rise is one in which “intelligence is obsolete.†Koons’ iconic “product line†sculptures–the latest of which, a huge steel heart, looks “incredibly costly†and “as sweet as dime-store perfume‖are turned out in a factory employing some 90 assistants. (“Rabbit,” shown here, is a stainless-steel cast of an inflatable bunny.) The steel heart, chirps Schjeldahl, “apostrophizes our present era of plutocratic democracy, sinking scads of money in a gesture of solidarity with lower-class taste.†And that major artist, X-ray vision-ness? “We might wish for a better artist to manifest our time, but that would probably amount to wanting a better time.â€

2. Annie Proulx, “Tits-Up in a Ditch.†This is the sloppily-tricked-out, unreinforced Humvee underbelly of the want-of-a-better-time-to-live-through. A story about Dick Cheney’s Wyoming and Dick Cheney’s Iraq War, in which a young woman, Dakotah, begins her “descent into the dark, watery mud†of our time, when she discovers that the only words she has to describe her Iraq experience are the gnawed-end clichés of the grandfather she hates.

3. Ron Chast cartoon book: “How to Live on One Hour of Sleep Per Night.â€

4. Vladimir Nabokov, “Natasha.†A newly-translated story whetting our appetite for the unfinished novel, The Original of Laura, to be published despite Nabokov’s dying request that it be burned. Scatter has considered the dilemma, to burn or not to burn. We’re a bit ambivalent, can see both sides of the match, but we’re eager to read it. Great “Natasha” sentence: “The music of geographical names.â€

5. Tobias Wolff, “Winter Light.†Faith sparked by bleak Ingmar Bergman film; and not.

6. Louis Menand on a biography of Ezra Pound. Menand passes over Pound’s Fascist period without even discussing whether it compromised his art. Perhaps in our time we’re ashamed to address this question? Or don’t care? I’m not sure that’s what compromised Pound’s art, but the thought reminded me of what I read in Russell Banks’ Dreaming Up America (Seven Stories Press, $21.95, 144 pages), a transcript of Banks’ commentary for a French television documentary about American cinema. Banks discusses the mythmaking movies that are “occasionally subversive†but most often “serve the pleasures of the powers that be,†starting with the “fountainhead†of American cinema, The Birth of a Nation. Dreaming Up America is a brilliant little book, but in an analysis that emphasizes the dark racism at the heart of America’s story, how useful is it to repeat the old saw about the art of The Birth of a Nation, which presents, as Banks notes, the “bloody, brutal work of the Ku Klux Klan†without apology and “as a point of prideâ€? “It cannot be ignored,†says Banks, that The Birth of a Nation is an extraordinary film—one that’s loathsome ethically, and that’s politically and spiritually loathsome as well, and yet artistically it’s great.†Why not say simply that it’s awful, with no redeeming value at all.

7. Wallace Stevens. Not named in Menand’s list of poets and writers around Pound, and I think of his poem “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird.” Here’s one way:

I do not know which to prefer,

The beauty of inflections

Or the beauty of innuendos,

The blackbird whistling

Or just after.

8. Elizabeth Kolbert on Bucky Fuller, who called himself “Guinea Pig B,†and did a lot of weird stuff, including inventing the ever-leaky geodesic dome and coining “spaceship earth.†The erratic genius has us scratching our figurative heads still. To sum up the puzzle, Kolbert quotes Hugh Kenner, who said he could make Fuller’s talk “seem systematic. I could also make it seem like a string of platitudes, or like a set of notions never entertained before, or like a delirium.â€

9. James Wood on God and the problem of suffering in the world. Is suffering punishment for sin, a test of virtue, or evil to be vanquished by God? Stay tuned, as the world goes “hellmouth.” Wood catalogs a newspaper’s inky current of despair: earthquake, cyclone, bomb attack, missile strike, torture. In the face of this, there are the ranters for belief, the ranters for unbelief, and the ranters with “an aggrieved nostalgia for belief.” I prefer the quiet nonbeliever Melville, who could “neither believe, nor be comfortable in his unbelief,” as Hawthorne reported, and who “pretty much made up his mind to be annihilated.”

10. Nancy Franklin reviewing summer TV’s “Swingtown.†Dreary me. But Franklin envies the young actors in it, who “have to live through the seventies only once.â€

11. The Talk of the Town. Over the Memorial Day weekend, Fordham University hosted a conference, “The Sopranos: A Wake,” including a four-hour bus trip to “Sopranos” locations in New Jersey. Meanwhile, archaeologists hail Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Skull, expecting “a spike in kids who want to become archaeologists” when they go to university. I don’t know.

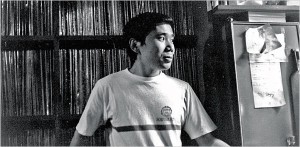

12. Haruki Murakami, “The Running Novelist,†an excerpt from the forthcoming memoir, What I Talk About When I Talk About Running. Matter-of-factness may seem a strange charm to claim for a writer. But that’s what I love about Murakami’s stories, whether they are realistic, or veer off into surreal fantasy. Told as matter-of-factly as the ingredients on a box of Kashi cereal. Writer sees as readers do: “And with each work my readership—the one-in-ten repeaters—increased. Those readers, most of whom were young, would wait patiently for my next book to appear, then buy it and read it as soon as it hit the bookstores.†I’m no longer that young, but I begin a Murakami book when I pick it up from the display, pay for it without breaking stride, find a safe, out of the way corner where I won’t be run over by a truck or struck by lightning, and finish it, work and family be damned. Next.

12. Haruki Murakami, “The Running Novelist,†an excerpt from the forthcoming memoir, What I Talk About When I Talk About Running. Matter-of-factness may seem a strange charm to claim for a writer. But that’s what I love about Murakami’s stories, whether they are realistic, or veer off into surreal fantasy. Told as matter-of-factly as the ingredients on a box of Kashi cereal. Writer sees as readers do: “And with each work my readership—the one-in-ten repeaters—increased. Those readers, most of whom were young, would wait patiently for my next book to appear, then buy it and read it as soon as it hit the bookstores.†I’m no longer that young, but I begin a Murakami book when I pick it up from the display, pay for it without breaking stride, find a safe, out of the way corner where I won’t be run over by a truck or struck by lightning, and finish it, work and family be damned. Next.

OK, that’s only twelve. But I’m superstitious. And they don’t number the thirteenth floor of hotels, either; or so I’m told.

*Photo of Haruki Murakami at his jazz bar, Peter Cat, in Sendagaya, Tokyo, 1978.