Art Scatter has followed with more than passing interest the ongoing debates over the future of journalism in the U.S. I started to type “newspapers,” because the rapid decline of the large corporations that own most of the larger daily newspapers in the country has already wiped out thousands of journalist positions in the country, at exactly the moment that television and radio news have also hit the skids. But we now understand that “newspaper” and “journalism” are not synonymous, that in fact journalism of wildly varying quality can be found just about everywhere, from newspapers to electronic media to digital media. Even at comedy clubs.

Just to get everyone up-to-date with the latest arguments about the decline of journalism and how to reverse it, we have some links!

The most radical suggestion I’ve heard recently for saving the free press comes from Robert W. McChesney and John Nichols, writing in the The Nation. I knew Mr. McChesney back when we both worked at the Seattle Sun, a now-defunct alternative weekly paper, in the late 1970s. In fact, he succeeded me as publisher at the Sun, though I don’t think he lasted as long as I did before he escaped to academia. He’s now a professor in the Department of Communications at the University of Illinois, and he’s devoted his career to describing and critiquing the power of tightly controlled corporate media in various manifestations.

McChesney and Nichols argue that our idea of a free press needs to be expanded exponentially and funded by government subsidies. Some would be indirect in the form of $200 tax credits for taxpayers who subscribe to a daily newspaper of their choice. “We could see this evolving into a system to provide tax credits for online subscriptions as well.” For a paper like The Oregonian, that would add up to something approaching $60 million, though McChesney and Nichols are hoping for something better than The Oregonian. And, in fact, they are hoping that competitors to The Oregonian enter the field.

They also want direct subsidies to fund public journalism along the lines of European models. They even want to fund extensive journalism programs in public schools — how else can you get young people excited about what’s going on their world? And really, that’s the role of journalism in a democracy: to keep we, the citizens, both and informed about and engaged in our government, our culture and our sports teams. OK. I added those last two part myself.

I think of Steven Berlin Johnson as a futurist who sees the future in the past, and his speech at SXSW in Austin on the future of media does exactly that. He extrapolates from his experience with the rapid expansion of tech journalism during the past 25 years or so, and doesn’t really see a problem. Sure, there will be dislocations, but the quantity and quality of journalism as a whole is likely to expand as rapidly as the quality of one of its parts, tech journalism. And frankly, when I think about it, he might be right already for national-level issues. But it’s the local where we live, and the local where we have the greatest fear about the loss of journalism. Twenty fewer commentators on the stimulus package wouldn’t be such a great loss. One fewer person covering Portland Public Schools on a regular basis would get us down to near-zero. Would a little niche-ecology of bloggers rush in to fill the void? I’m thinking of greater outreach by the school district itself and the teachers’ union, maybe the PTA, along with various educational observers of various stripes. Maybe so. Johnson is a smart guy, so he could be right. And his suggestion can be easily followed — do nothing!

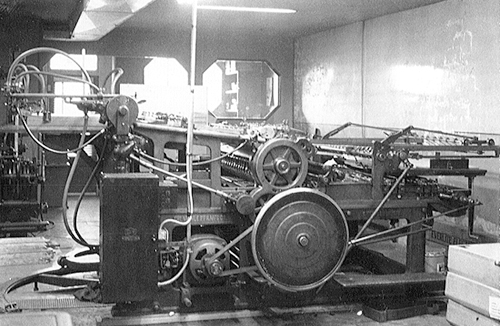

Which is where Clay Shirky, an Internet theoretician, ends up in his looping essay on the history of information revolutions. We can debate his “read” of recent American media history, which boils down to expensive printing presses losing out to cheap online servers. (McChesney and Nichols, for example, would probably suggest that the mega-media corporations became addicted to the massive profit margins of newspapers and failed to invest in them, instead wringing every penny out of them that they could.) But his essay is still a fascinating tour of the press since Gutenberg.

We’ll stop for now with an short essay by Alan Mutter from his Reflections of a Newsosaur blog. Mutter has been a journalist, though he moved on to the Silicon Valley, and his blog attempts 1) to describe how dire things are for the news business, and 2) what positive signs he sees out there for the future. That’s what the linked post does.