What is craft? What is art? What is folk art? Outsider art? Contemporary art?

Are the distinctions real? Do they matter, or are they intellectual games people play, rococo road blocks in the path of direct emotional response to aesthetic objects?

Oh — and what’s a museum supposed to be, anyway?

Dumb questions, maybe. Or, as I prefer to think, basic questions — and sometimes, when you’re staring a big change in the face, basic questions are very good things to ask.

Here’s another one: How many museums does a city need to have a healthy critical mass?

Like a lot of people, I’ve been pondering the impending takeover of Portland’s financially sinking Museum of Contemporary Craft by the expansion-minded Pacific Northwest College of Art, a merger that might become final next month. The question at this point is no longer, “Is this a good idea?”. Barring the sudden swooping down from the heavens of a previously unsuspected angel, some sort of merger seems necessary if the museum is to survive, and this is the one that’s been worked out. So the question now is, “How will this work to the best long-term advantage of both institutions?”

Lots of people have been thinking about this, including The Oregonian’s D.K. Row, Port’s Jeff Jahn, and fellow Scatterer Barry Johnson, on his alternate-universe blog (and Oregonian column) Portland Arts Watch. And we’re in the midst of a series of public forums on the subject. So let me come at it a little sideways.

A couple of weeks ago I had a long lunch with Namita Wiggers, the craft museum’s curator, and Rebecca Burrell, its marketing specialist. What I detected from them, as others have also, is genuine enthusiasm for the possibilities — an enthusiasm that seems not just the rush of gratitude and relief that a drowning person feels when she catches onto a lifeline, but an excitement over how an alliance with the art school can strengthen the museum.

Then I spent some time with the museum’s new book, Unpacking the Collection: Selections From the Museum of Contemporary Craft, and I was reminded to what an extraordinary extent the history of this organization is linked to the history of ceramics in Oregon and elsewhere.

Earlier, I decided to take advantage of a trip to Seattle a couple of months ago by visiting the nearby Bellevue Arts Museum, hoping that a look around might offer some new perspectives on the Portland museum’s problems and possibilities.

The Bellevue museum is the next-nearest museum to Portland that’s devoted to craft (the second-closest, actually; there’s the Museum of Glass in Tacoma, but that museum, although it’s absolutely rooted in a craft ethic, also has a much narrower focus). With the Museum of Contemporary Craft, the two Puget Sound museums create the northern outposts of an emerging West Coast circuit of craft museums that includes San Francisco Museum of Craft + Design and the Museum of Craft and Folk Art, also in San Francisco. (There are others in California and the Southwest, too, as well as the Canadian Craft Museum, in Vancouver, British Columbia.)

The redefining of the Museum of Contemporary Craft comes at a time when craft itself is being redefined. It used to be easy. Craft was the art of the utilitarian and the handmade — an art of the people, appreciated even by the privileged. It often got clumped with words like “folk,” “naive,” “outsider” and “ethnic,” although its most consistent hallmark was a sophisticated simplicity of form.

The redefining of the Museum of Contemporary Craft comes at a time when craft itself is being redefined. It used to be easy. Craft was the art of the utilitarian and the handmade — an art of the people, appreciated even by the privileged. It often got clumped with words like “folk,” “naive,” “outsider” and “ethnic,” although its most consistent hallmark was a sophisticated simplicity of form.

But the worlds of craft and “high” art have been drawing closer together for a long time now. Craft is becoming conceptual and metaphorical, often giving a token nod to its practical roots as it strives to become an object of pure contemplation or social commentary. And contemporary artists are freely adopting the materials and forms of craft to their own purposes, so it’s often difficult or impossible to say whether a specific work is “craft” or “art.” It’s a smudgy landscape where the fences aren’t defined. And while some fret over that, others see opportunity. “I find those smudgy areas exciting,” Wiggers says. “That’s where the interesting stuff is.”

Then, what makes a craft museum a museum of craft? And is there a danger that, in pursuing the brass ring of high art, the craft world loses its moorings and becomes neither one nor the other, but some floating, indeterminate thing? Is that a problem? In what ways is or should the Museum of Contemporary Craft be different from the Portland Art Museum?

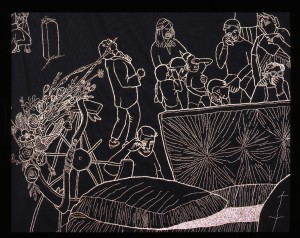

It’s not difficult to imagine the craft museum’s current shows of work by textile artists Darrel Morris and Mandy Greer being presented instead at the art museum. Nor is it difficult to imagine M.K. Guth’s recent installation at the Portland Art Museum, after its annointment by the Whitney Biennial, being featured at the craft museum. The art museum’s excellent collections of Native American and Asian art are suffused with fine craftsmanship, and in fact Native American art is often a staple of craft museums — as it should be, because so much of it reflects the essence of the idea of the beautiful everyday object.

It’s good to remember, as a look through Unpacking the Collection suggests, that the Museum of Contemporary Craft is something of an accidental museum. It was founded in 1937 as the Oregon Ceramic Studio, and its original emphasis was on the “Studio” — it was a place to make objects, not to collect or catalog or display them, although exhibitions were a part of the program almost from the beginning. It was very much an active player in the 20th century ceramics movement, and over the years it did collect a lot of objects, helping to tip it eventually from a place to make art to a place to sell and display it. If the original focus was narrowly on ceramics, it has broadened. And many of the pieces in the permanent collection of more than 1,000 works are high-quality, made by artists including Robert Arneson, Linda and Joe Apodaca, Tom Hardy, Shoji Hamada, Lydia Herrick Hodge (who founded the ceramics studio), Peter Voulkos, John Mason, Ken Shores, Gertrud and Otto Natzler, Sam Maloof, Frank Boyden, Toshiku Tazeaku and, more recently, Kyoko Tokumaru, Rick Bartow and Hildur Bjarnadottir. Notice that a lot of those names are equally familiar in fine-arts circles.

It’s good to remember, as a look through Unpacking the Collection suggests, that the Museum of Contemporary Craft is something of an accidental museum. It was founded in 1937 as the Oregon Ceramic Studio, and its original emphasis was on the “Studio” — it was a place to make objects, not to collect or catalog or display them, although exhibitions were a part of the program almost from the beginning. It was very much an active player in the 20th century ceramics movement, and over the years it did collect a lot of objects, helping to tip it eventually from a place to make art to a place to sell and display it. If the original focus was narrowly on ceramics, it has broadened. And many of the pieces in the permanent collection of more than 1,000 works are high-quality, made by artists including Robert Arneson, Linda and Joe Apodaca, Tom Hardy, Shoji Hamada, Lydia Herrick Hodge (who founded the ceramics studio), Peter Voulkos, John Mason, Ken Shores, Gertrud and Otto Natzler, Sam Maloof, Frank Boyden, Toshiku Tazeaku and, more recently, Kyoko Tokumaru, Rick Bartow and Hildur Bjarnadottir. Notice that a lot of those names are equally familiar in fine-arts circles.

In its years on Corbett Avenue the museum evolved from studio to gallery to gallery/museum, but it wasn’t until its move downtown in summer 2007 to the DeSoto Building project in the North Park Blocks, with high-quality gallerist neighbors Froelick, Blue Sky, Augen and Charles A. Hartman, that it fully emerged as a museum. That makes it a baby in the museum world, although a baby with a long lineage. And at the root of its problems is that it tried to be a grownup when it hadn’t developed its structural muscles yet. There’s a huge difference between a gallery and a museum, and most of it doesn’t show on the surface. If all goes well, linking with the structurally more stable art college could help the museum step more responsibly into maturity.

Which leads to the big question in a lot of minds: How is this merger going to work, anyway? If the tie-in with the college brings financial and structural stability, will it also significantly alter what the museum is and what it does? How will the school, whose main interest is educating contemporary artists, connect artistically with the museum, whose focus — indeed, whose entire purpose — is craft? People are looking at the vital world of design, an especially important field of interest in Portland, as the connecting link. That could be a very good bet.

But if design and those “smudgy areas” of contemporary craft and art make the museum and the college potentially congenial partners, what happens to the focus on more traditional handmade objects — that stubbornly individual crafted scene that’s still a lively and, to many people, crucial part of artmaking in the Pacific Northwest? Even if the school approaches this takeover with the best intentions (and it seems to be proceeding in a genuinely benevolent, if of necessity not entirely disinterested, way) will its own agenda gradually engulf the museum’s? What sort of firewalls are being put in place to ensure the museum’s independence within its larger circle of dependency?

“You’re looking at one of the best firewalls,” the museum’s Burrell said, nodding her head toward Wiggers. The museum’s curator, Burrell added, is not a person to be easily steamrollered.

True enough. Wiggers has knowledge, and vision, and a healthy stubborn streak, all good qualities in a curator, and she is likely to stick up fiercely for what she thinks is right for the museum. But organizations need to look beyond individuals: Even if she’s the best firewall in the world, what happens when she’s gone? Clear lines of authority and purpose need to be drawn institutionally, maintaining some structural distance even as the two organizations actively seek ways to collaborate on projects to the benefit of both. Mergers are tricky under the best of circumstances, and trickier yet when one partner enters the merger from a position of weakness, as the museum does here.

True enough. Wiggers has knowledge, and vision, and a healthy stubborn streak, all good qualities in a curator, and she is likely to stick up fiercely for what she thinks is right for the museum. But organizations need to look beyond individuals: Even if she’s the best firewall in the world, what happens when she’s gone? Clear lines of authority and purpose need to be drawn institutionally, maintaining some structural distance even as the two organizations actively seek ways to collaborate on projects to the benefit of both. Mergers are tricky under the best of circumstances, and trickier yet when one partner enters the merger from a position of weakness, as the museum does here.

The Bellevue Arts Museum has its own problems, not least of which is its location in the dead zone of downtown Bellevue, a collection of shiny, characterless national chain outlets: It’s as if the Bridgeport Village shopping center were Portland’s urban core. Foot traffic is sparse, and museum admission is a hefty $9 — perhaps the hangover from a staff embezzlement a few years ago that left the museum’s coffers reeling and was an acute embarrassment. And unlike Portland’s craft museum, it has no permanent collection of its own.

But it also has a handsome building (with free parking in the basement!) that has ample space for three well-displayed exhibits, allowing it to mix its program for a variety of tastes. When I visited, the mix was smart. “American Quilt Classics 1800-1980,” a touring exhibition assembled by North Carolina’s Mint Museum of Craft + Design, played to tradition with taste and intelligence. “Intertwined” was a superb show of contemporary basketry, from gorgeous Native American and Japanese to cutting-edge pieces, from the collection of Sara and David Lieberman. And I was lucky to get in on the end of “Melt,” Tip Toland’s show of fascinating life-sized, hyperrealistic clay figures along the lines of Duane Hanson or John De Andrea, but with Toland’s own sweet and very human twist. (Toland was an artist in residence at Contemporary Craft Gallery, one of the Portland craft museum’s earlier identities, in 1983.) Among them, the three shows covered a lot of craft/art territory.

More importantly, the Bellevue museum is part of a Seattle/Puget Sound cluster of museums that overlap, intersect, and prod one another, creating a lively scene that is greater than any of its parts. There are Bellevue; the Tacoma Glass Museum; the Northwest-centric Tacoma Art Museum; the representationalist Frye; the contemporary Henry Art Gallery; and at the center, the generalist Seattle Art Museum, with its Asian art satellite in Volunteer Park.

That’s the museum critical mass that Portland lacks, and it’s why the Museum of Contemporary Craft deal is bigger than itself — it’s the only thing that’s keeping Portland from being a one-museum town. That makes its survival — and its ability to define its own place in the firmament, even when the lines of contemporary art and craft are getting fuzzier — of heightened interest to the whole arts community. The Portland Art Museum is a good regional general-interest museum, but it can’t be all things to all people, and it shouldn’t have to be. There’s not just safety in numbers, there’s vitality, too. A strong craft museum takes some pressure off and creates some interesting cross-currents. A good contemporary art museum, which people have been trying unsuccessfully to get going at least since the days of the Portland Center for the Visual Arts in the 1970s and ’80s, would up the ante even more.

Academic galleries at Lewis & Clark, Reed, Marylhurst and Clark College run good, challenging programs, but they aren’t museums, and it’s unfair to ask them to be. Salem’s Hallie Ford and the Jordan Schnitzer at the University of Oregon have stimulating programming but are a little far-flung, and Maryhill Museum, in its clifftop desert fortress more than 100 miles east of town, stands in splendid idiosyncratic isolation.

Good museums don’t just show what’s hot and sellable — that’s what commercial galleries do. Museums take a long view. They collect and they nurture. They hold the past, and they constantly reassess it in light of the present and future. They look for the next big moment. They catalog, they restore, they make judgments about what’s significant and what is not so much. They bring the outside world of ideas inside their walls. They are monkish, and they are populist. They matter to the most esoteric of specialists and the most casual of visitors. They uphold standards, and they entertain. They do stuff for almost nobody to see, and stuff for almost anybody to see. They’re marvelous places, really, or at the least, marvelous possibilities.

Today, the Museum of Contemporary Craft is a marvelous possibility. It needs to make sure its new partnership is creative instead of partisan. It needs to shoot for the future that design and contemporary art promise. It needs to hold on to the past with resolution but not nostalgia. It needs, god help it, some structural and financial terra firma to stand on. And it needs to understand that in a one-and-a-half-horse town, a lot more than a two-dollar bet is riding on how it runs the race.

Pingback: Heard any good theater lately? | Oregon ArtsWatch()