By Bob Hicks

Actors have a parlor trick they like to pull out to amaze and amuse their non-thespian friends. I’m not sure if it has an accepted given name, but I sometimes call it the “laugh-cry game.” It’s simple, really: They cover their faces, start making an odd guttural sound, and challenge you to tell whether they’re laughing or crying. In terms of technique, both actions come out of the same place.

It’s fitting that the art of acting is so often depicted with drawings of the tragic and comic masks, because the comic and tragic are so often barely a whisker’s width separated from each other. Tragedy gets the respect. Comedy gets the love, if often reluctantly. But really, the balance is a lot closer. Remember, Chekhov insisted his mournful plays were comedies.

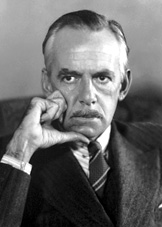

I think of this because the big deal in Puddletown this weekend is Saturday night’s opening of Long Day’s Journey Into Night, Eugene O’Neill‘s imperial American classic, at Artists Repertory Theatre. This production has Serious written all over it. A co-production with Australia’s Sydney Theatre Company, it stars occasional Oregonian William Hurt as the destructive Tyrone family patriarch, and it drew sparkling reviews in its recently closed Sydney run. I look forward to it not just because it arrives with stellar recommendations but also because O’Neill was in a very real sense the father of American theater, our first true genius. That he was such a morose son of a bitch was the luck of the draw. France got Moliere, the satiric comedian. England got Shakespeare, the astonishing Everyman. We got Old Bleak House, and few writers have ever done bleak better: O’Neill paints loss in despairingly seductive strokes of love.

I think of this because the big deal in Puddletown this weekend is Saturday night’s opening of Long Day’s Journey Into Night, Eugene O’Neill‘s imperial American classic, at Artists Repertory Theatre. This production has Serious written all over it. A co-production with Australia’s Sydney Theatre Company, it stars occasional Oregonian William Hurt as the destructive Tyrone family patriarch, and it drew sparkling reviews in its recently closed Sydney run. I look forward to it not just because it arrives with stellar recommendations but also because O’Neill was in a very real sense the father of American theater, our first true genius. That he was such a morose son of a bitch was the luck of the draw. France got Moliere, the satiric comedian. England got Shakespeare, the astonishing Everyman. We got Old Bleak House, and few writers have ever done bleak better: O’Neill paints loss in despairingly seductive strokes of love.

Good laughs are nothing to sniff at.

I am hardly a Reader’s Digest man (although as a boy I was, thanks to my beloved grandmother’s annual Christmas gift of a renewal subscription) but I wholeheartedly agree with the sentiment behind the magazine’s trademarked feature, Laughter Is the Best Medicine. Our times can be tragic enough. A little good comedy helps us bear up under them.

I was reminded of that by the Portland dance troupe BodyVox‘s announcement of its new season, which will include a Halloween-season spectacle called BloodyVox (the picture at top is from it) as well as a program devoted to the wonderfully silly short films of frequent BodyVox collaborator Mitchell Rose. BodyVox is a gifted company, but humor is often looked on suspiciously in the cloistered world of contemporary dance, and as a result, BodyVox, which shares the brash and essentially optimistic spirit of America before it burdened itself with the sins and responsibilities of Rome, gets short-sheeted in the rumpled bed of critical opinion. That’s tough to laugh off, although BodyVox seems to manage it.

Even O’Neill sometimes needed a break from himself, and Artists Rep will follow Long Day’s Journey in September and October with a fresh production of Ah, Wilderness!, O’Neill’s small-town Fourth of July nostalgia piece, the closest he ever came to writing a comedy. Ah, Wilderness! doesn’t get the props that Long Day’s does, nor should it: It’s a smaller accomplishment. Still, it’s a very good American play, and it’s part of the complex beast that Eugene O’Neill was: He liked a good laugh now and again, too.

Even O’Neill sometimes needed a break from himself, and Artists Rep will follow Long Day’s Journey in September and October with a fresh production of Ah, Wilderness!, O’Neill’s small-town Fourth of July nostalgia piece, the closest he ever came to writing a comedy. Ah, Wilderness! doesn’t get the props that Long Day’s does, nor should it: It’s a smaller accomplishment. Still, it’s a very good American play, and it’s part of the complex beast that Eugene O’Neill was: He liked a good laugh now and again, too.

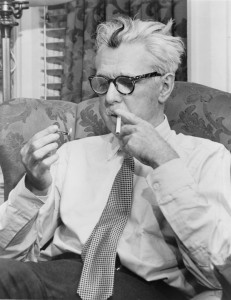

For one thing, laughter soothes the savage breast, and who knows the savagery of the breast better than a born tragedian? I like to think I’m better-balanced than O’Neill, but I’m familiar with both sides of the mask. Feeling restless and out of sorts the other day, I rustled through my bookshelves and picked out my 1959 copy of The Years With Ross, James Thurber‘s book-length reminiscence of his long social and professional friendship with Harold Ross, the legendary founding editor of The New Yorker.

What I rediscovered was a volume that is light and dark interwoven, a complex portrait of buffoonery and admiration, valor and sheepishness, friendship and competition, grace and venality. Thurber, that gentle wit, could be savage about his old friend, and condescending, and sometimes just plain mean. He made a caricature of this largely unschooled man of the wide unwashed West, making sport of his real or imagined gaucheries — and then, with the flick of a phrase, he brought you up short with the beauty of the man’s soul and the singular greatness of his talent. The things that words can do!

What I rediscovered was a volume that is light and dark interwoven, a complex portrait of buffoonery and admiration, valor and sheepishness, friendship and competition, grace and venality. Thurber, that gentle wit, could be savage about his old friend, and condescending, and sometimes just plain mean. He made a caricature of this largely unschooled man of the wide unwashed West, making sport of his real or imagined gaucheries — and then, with the flick of a phrase, he brought you up short with the beauty of the man’s soul and the singular greatness of his talent. The things that words can do!

Adam Gopnik, in his introduction to the most recent paperback reprint of The Years With Ross, pronounced Thurber “… among the most moving and soulful, not to mention one of the funniest, twentieth-century American writers.”

Gopnik elaborates:

He was also probably the best and purest tonal writer we’ve ever had. Thurber is a tonal writer in the simple sense that his is a voice we know rather than a set of jokes we laugh at. Where almost every comic writer before him comes at us in aphorisms or epigrams — or else in the epigram’s cousin from Milwaukee, the wisecrack — Thurber just makes sentences. … Thurber is memorable in paragraphs and pages rather than in lines. He doesn’t “turn phrases”; he just turns the corner on to the next sentence. No one worked harder or went further to slim down the space between American speaking and writing voices, between the way we talk and the way we write.

An even earlier American literary comedian, Mark Twain, was also a humorist rather than a joke-teller, although like Thurber he could pull off a rip-roaring joke when the occasion called for it. Twain, a kind of flip-side O’Neill, could be devastatingly serious behind the clown mask, as I believe Thurber, in his smaller and quieter way, also could be. Thurber was a civilized New Yorker with roots in Columbus, Ohio, and he exploited the comic possibilities of modern urban neurosis as well as anyone this side of Cole Porter (Peru, Indiana). Still, you can find a little bit of hayseed and a broad streak of restless frustrated frontier energy in a lot of his characters and situations, and those things made Harold Ross (Aspen, Colorado, before it became a playground of the fabulously fabulous) in many ways an ideal Thurber hero.

Thurber’s approaches to writing and humor rose from closely observing the shambling inventiveness of the natural American oddball, a type that has often leaned more heavily on native shrewdness and immediate experience than on the accumulated wisdom of the ages. This exaggerated fellow (think Mike Fink, Davy Crockett) is pre-Twain, perhaps a creation of the rowdy Jacksonian era, although Yankee Doodle Dandy suggests he might be even older: whatever his roots, he’s at once appalling, heroic, and uproariously funny.

Thurber’s approaches to writing and humor rose from closely observing the shambling inventiveness of the natural American oddball, a type that has often leaned more heavily on native shrewdness and immediate experience than on the accumulated wisdom of the ages. This exaggerated fellow (think Mike Fink, Davy Crockett) is pre-Twain, perhaps a creation of the rowdy Jacksonian era, although Yankee Doodle Dandy suggests he might be even older: whatever his roots, he’s at once appalling, heroic, and uproariously funny.

Maybe we don’t have the sort of innocence anymore to appreciate this sort of force of nature, or we’d be celebrating the broad proletarian wit of Sarah Palin. (Or maybe not. Ross was a good deal more genuine and vastly more accomplished in his chosen profession than the Sage of Wasilla. If Tina Fey is a wit, Sarah Palin is barely half that.) Like any good artist, Thurber ruthlessly refined his raw material. Gopnik quotes the great Joseph Mitchell‘s explanation of what distinguished the work of his fellow New Yorker writers: each had “a kind of wild exactitude of his own.” “Wild exactitude” goes a long way toward describing the sort of editor, and man, that Harold Ross was, at least the Ross that Thurber presented to the world.

In the end, Thurber’s comic portrait of Ross is anything but comic. No, that’s not right. It’s comic, but it opens into something much bigger than it seems. Ross dies, of course. After he gives up most of his pleasurable vices, the Big C gets him. Literarily speaking, this could be pathetic, a mere limping into denouement. Thurber doesn’t allow that. He turns the corner on to the next sentence, and the next, and the next, and finally, astonished, I realized I was weeping for this strange and lovely man, Harold Ross, whom I had never known, who died in 1951, when I was not quite four years old.

Maybe Long Day’s Journey Into Night will have the same effect. If it doesn’t, will that be a tragedy?

*

ILLUSTRATIONS, from top:

- What’s holding things up? Jamey Hampton in “BloodyVox.” Photo: Michael Shay, Polara Studios

- Robyn Nevin and William Hurt in “Long Day’s Journey Into Night.” Photo: Brett Boardman

- Eugene O’Neill in 1936, when he won the Nobel Prize for literature. Nobel Foundation/Wikimedia Commons

- James Thurber in 1954. Library of Congress, New York World-Telegram & Sun Collection/Wikimedia Commons. Photo: Fred Palumbo, World Telegram staff photographer

- Harold Ross during World War I, about 1918. Wikimedia Commons