So Monday night I was jammed against a wall at Jimmy Mak’s, scribbling down words of wisdom from Portland’s reigning creative economy king, architect Brad Cloepfil of Allied Works. I got there a little late: Cloepfil had already been introduced by Randy Gragg, editor of Portland Spaces magazine, the sponsoring organization, and had begun a preparatory slide show of his recent work, most notably his remake of the Museum of Arts and Design at 2 Columbus Circle in New York. And the room was completely filled; I was lucky to get my little piece of wall. But even in my scrunched state, I found it difficult to resist Cloepfil. He’s clear-headed, speaks directly, has a dry sense of humor, doesn’t conceal his real feelings (maybe the martinis had something to do with that) and most important, has an obvious passion for Portland, what it is and what it could become.Â

So Monday night I was jammed against a wall at Jimmy Mak’s, scribbling down words of wisdom from Portland’s reigning creative economy king, architect Brad Cloepfil of Allied Works. I got there a little late: Cloepfil had already been introduced by Randy Gragg, editor of Portland Spaces magazine, the sponsoring organization, and had begun a preparatory slide show of his recent work, most notably his remake of the Museum of Arts and Design at 2 Columbus Circle in New York. And the room was completely filled; I was lucky to get my little piece of wall. But even in my scrunched state, I found it difficult to resist Cloepfil. He’s clear-headed, speaks directly, has a dry sense of humor, doesn’t conceal his real feelings (maybe the martinis had something to do with that) and most important, has an obvious passion for Portland, what it is and what it could become.Â

Â

He was also comfortable with Gragg’s moderation, maybe because Gragg was a Cloepfil supporter during his years of writing architecture criticism for The Oregonian (full disclosure: where I edited him for several years). It’s hard to get the gist of 90 minutes of talk, so I’ll resort to picking out the most provocative quotes, roughly in the order in which they occurred Monday night.

Continue reading A little Brad Cloepfil wisdom coming your way

American Earth: environmental writing for the age(s)

“He had merely waked up one morning again in the country of the blue and had stayed there with a good conscience and a great idea.”

–Henry James, “The Next Time”

American Earth: Environmental Writing Since Thoreau arrived on April 22, Earth Day. Edited by Bill McKibben, with a Foreword by Al Gore, and published by Library of America on acid-free paper, it is a volume designed to last for generations. But will the selection from 102 writers have relevance past our own age? Can environmental writing focus the debate on critical issues in such a way that, as Al Gore suggests, “American environmentalism will shape our standing in the worldâ€? Will folks spend $40 to find out? Lugging around this thousand-plus page book will alter my gait, but will it change my “environmental perception”? The answer to that may be weeks away as I dig in. Here, scatter-shot, are my initial reactions.

American Earth: Environmental Writing Since Thoreau arrived on April 22, Earth Day. Edited by Bill McKibben, with a Foreword by Al Gore, and published by Library of America on acid-free paper, it is a volume designed to last for generations. But will the selection from 102 writers have relevance past our own age? Can environmental writing focus the debate on critical issues in such a way that, as Al Gore suggests, “American environmentalism will shape our standing in the worldâ€? Will folks spend $40 to find out? Lugging around this thousand-plus page book will alter my gait, but will it change my “environmental perception”? The answer to that may be weeks away as I dig in. Here, scatter-shot, are my initial reactions.

Most overrated of the 102 writers. Edward Abbey. I know I cut against the grain here. McKibben describes Abbey as funny, crude and politically incorrect, “a master of anarchy and irreverence.†I don’t buy it. He was a misanthrope with a sense of privilege he expected others to respect. To wit, McKibben’s description of a day spent with Abbey at his “beloved†Arches National Monument: “Because he refused to let me pay tribute in the form of a $5 dollar admission fee to park rangers at the gate, we instead drove for miles, took down a fence, and forced my rental car through a series of improbable rutted washes to reach our goal, cackling the whole way.†Why not an all-terrain vehicle?

Continue reading American Earth: environmental writing for the age(s)

Artists in China: Good foreign policy

A Jeff Koons planted in the yard of the new American embassy in China. And not just a Koons “Tulips” sculpture, either. Work by Maya Lin and Louise Bourgeois will also be there. Robert Rauschenberg and Martin Puryear, too. According to the Art Newspaper, the U.S. government is spending $800,000 on (mostly) commissioned artworks for the embassy, a mix of Chinese and American artists. And for once, I’m totally aligned with American foreign policy. China needs the subversion of Puryear, the gentle suggestions of Lin and maybe even the imaginative flights of Koons, which should fit in well in the go-go Chinese economy. A very small number of people will see them, of course, but it’s the idea of the thing: Art suggests an alternative reality, an alternative foreign policy, a new way of thinking about things. And if I were a Kantian, I might suggest a new Spirit.

A Jeff Koons planted in the yard of the new American embassy in China. And not just a Koons “Tulips” sculpture, either. Work by Maya Lin and Louise Bourgeois will also be there. Robert Rauschenberg and Martin Puryear, too. According to the Art Newspaper, the U.S. government is spending $800,000 on (mostly) commissioned artworks for the embassy, a mix of Chinese and American artists. And for once, I’m totally aligned with American foreign policy. China needs the subversion of Puryear, the gentle suggestions of Lin and maybe even the imaginative flights of Koons, which should fit in well in the go-go Chinese economy. A very small number of people will see them, of course, but it’s the idea of the thing: Art suggests an alternative reality, an alternative foreign policy, a new way of thinking about things. And if I were a Kantian, I might suggest a new Spirit.

Here’s Arthur C. Danto in The Nation, describing the work of Puryear at a MoMA exhibition late last year:

Once in a while, an artist appears whose work has high meaning and great craft but, most important, embodies what Kant, in the dense, sparse pages in which he advances his theory of art, called Spirit. “We say of certain products of which we expect that they should at least in part appear as beautiful art, they are without spirit, though we find nothing to blame in them on the score of taste,” Kant wrote. I’d like to revive the term for critical discourse. Not a single piece here is without spirit, which is in part what makes this exhibition almost uniquely exhilarating.

As the American experiment in democracy has foundered in recent decades (we could argue about this, but let’s just let the assertion stand for now, yes?), American artists have become more acute about it — pointing out failures, suggesting repairs, expressing anger and embarrassment. The most concentrated dose of oppositional politics I get in Portland, is in the art galleries (and maybe you could add the clubs, theaters and independent cinemas). At its best, it achieves the nuance of Puryear, which is what attracts philosopher Danto the most, perhaps, but it is awash in spirit. And I find I need it.

China? Yes, China needs it, too. The Chinese paintings described in the linked article show that artists there are just as sensitive to the human and environmental costs of China’s Market Authoritarianism as our artists are to their situation. And the idea of dropping Francis Bacon paintings into Qatar and raising Guggenheims and Louvres in Abu Dhabi, as we’ve remarked earlier? It will be fun to see the Picassos do their stuff — I suspect that the locals won’t be allowed to see them after a while. Too hot to handle.

China? Yes, China needs it, too. The Chinese paintings described in the linked article show that artists there are just as sensitive to the human and environmental costs of China’s Market Authoritarianism as our artists are to their situation. And the idea of dropping Francis Bacon paintings into Qatar and raising Guggenheims and Louvres in Abu Dhabi, as we’ve remarked earlier? It will be fun to see the Picassos do their stuff — I suspect that the locals won’t be allowed to see them after a while. Too hot to handle.

Aesthetic politics: Obama, Dewey, Potter, IFCC

Last night, watching the primary results roll in (and a strange Gregory Peck movie on Turner Movie Classics), I was struck yet again by the John Dewey in Barack Obama’s victory speech. I know, I know: I’ve managed to locate Dewey in just about everything. I didn’t post about it, but I even detected him in Dark Horse Comics chief Mike Richardson in his speech at the Stumptown Comic Fest. Richardson was terrific, by the way. So maybe I’m monomaniacal on this subject, as obsessive readers of Art Scatter already know.

Last night, watching the primary results roll in (and a strange Gregory Peck movie on Turner Movie Classics), I was struck yet again by the John Dewey in Barack Obama’s victory speech. I know, I know: I’ve managed to locate Dewey in just about everything. I didn’t post about it, but I even detected him in Dark Horse Comics chief Mike Richardson in his speech at the Stumptown Comic Fest. Richardson was terrific, by the way. So maybe I’m monomaniacal on this subject, as obsessive readers of Art Scatter already know.

Dewey and Obama. It has to do with process. Embedded within this speech and all of the others that I’ve heard Obama give (not a VERY large number), he tells you how he thinks he is going to bring about the change he talks about (to health care, foreign policy, education, etc.). He believes that Americans want their problems solved and are “looking for honest answers about the problems we face.” He believes they have the capacity to understand when they hear something that makes sense. He thinks they are ready to sit down and listen. And he is committed to “telling the truth — forcefully, repeatedly, confidently — and by trusting that the American people will embrace the need for change.” Not just the American people, either, because his foreign policy is built on the same process: talk. And he describes what he thinks freezes our process now — “I trust the American people’s desire to no longer be defined by our differences” — and why he thinks we can change, the hopes we have in common. And all of this is straight out of the American Pragmatism playbook.

Continue reading Aesthetic politics: Obama, Dewey, Potter, IFCC

Art New$: Rothko, Ferriso, financial advice to children

From time to time, events remind Art Scatter, even resolutely non-commercial as it, that in many precincts of the dominion money is commonly thought to make the world go ’round. It certainly sets the art world to spinning when some falls its way. Two recent examples:

From time to time, events remind Art Scatter, even resolutely non-commercial as it, that in many precincts of the dominion money is commonly thought to make the world go ’round. It certainly sets the art world to spinning when some falls its way. Two recent examples:

Mystery buyer of record-setting Rothko revealed! Way back last year, when the dollar was still worth something, a painting by Mark Rothko, White Center (Yellow, Pink and Lavender on Rose), 1950, sold for $72.8 million at Sotheby’s New York. Thanks to the Art Newspaper, we now know that Emir of Qatar and his wife bought it, along with Francis Bacon’s Study from Innocent X, which fetched a mere $52.7 million. We don’t usually report art auction doings, but in this case, we must point out that Rothko went to Benson High School Lincoln High School in Portland: Study art, kids!

Portland Art museum Director makes big money! D.K. Row’s thoughtful profile of Brian Ferriso contained one little nugget that might have raised some eyebrows — Ferriso makes $295,000 a year, which is still far less than his predecessor John Buchanan was paid. That’s still a lot of pizza, which Ferriso dined on at yummy Hot Lips Pizza when he first moved to town. But it’s on the low end of what museum directors are getting these days — $300,00 to $650,000 at small and mid-sized museums in the Midwest and South, according to artsmanagement.net, which explains the phenomenon. Hey kids, forget the art: take arts management classes instead!

Scatter considers the Nabokov Dilemma

Let’s just say your mother is a potter, an accomplished potter, a demanding potter. At the end of her life she started work on a new approach and made some progress. But then she took ill and joined the ceramic guild in the sky. Her last request? Destroy that last pot. What would you do? Honor her request by breaking it into a thousand pieces or honor her life’s work by keeping it?

Let’s just say your mother is a potter, an accomplished potter, a demanding potter. At the end of her life she started work on a new approach and made some progress. But then she took ill and joined the ceramic guild in the sky. Her last request? Destroy that last pot. What would you do? Honor her request by breaking it into a thousand pieces or honor her life’s work by keeping it?

That’s the dilemma faced by Dmitri Nabokov, son of Vladimir. To destroy his father’s last manuscript, actually the 138 index cards on which was assembling his last novel in typical Nabokovian fashion, or keep it and perhaps publish it. Perhaps you already know about this, yes? It’s made the mainstream media and the literary blogs, and the New York Times had an interview with Dmitri on Sunday.

So, should Dmitri burn The Original of Laura as Vladimir asked, light index card number one (with what, a kitchen match? a lighter made especially for the occasion? toss it into a good wood fire?) and watch the stack of them turn to ash? That’s what he said he wanted. Oops. Did you catch that “he said”? That’s a crack in the door through which Dmitri inserted his foot. Because what did Vladimir really want? Because sometimes he said things that he didn’t mean. We all do. And what we say can run counter to our deepest desire. And the request seems like such a gesture, a Romantic gesture. Dmitri knew his father (he even visited him recently to help him resolve the dilemma!). And he has decided to publish Laura. Scholars and the literary public rejoice!

Personally, I imagine that Vladimir meant what he said: Burn the damn thing. It’s caused me nothing but trouble. I keep getting sick. It’s not done. It’s not good. Yet. (I give him the “yet”.) It will be a weight off my shoulders, and I need to be unencumbered as I pass across the River Styx. Actually, I ‘m sure he wouldn’t say “weight off my shoulders” and I don’t know what his views on the afterworld are. But you get the idea. It’s a reasonable point of view. Dmitri defied his father.

Continue reading Scatter considers the Nabokov Dilemma

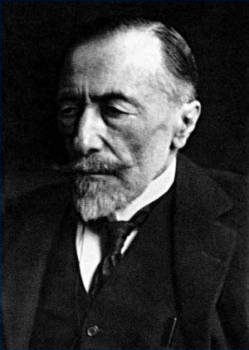

Joseph Conrad our contemporary

“At one time I thought that intelligent observation of facts was the best way of cheating the time allotted to us whether we want it or not; but now I have done with observation, too.â€

“Dreams are madness, my dear. It’s things that happen in the waking world, while one is asleep, that one would be glad to know the meaning of.â€

— Joseph Conrad, Victory

During this past week of “Mission Accomplished†ironies I have thought often of Joseph Conrad and his novel Victory, written before World War I began but not published until 1915. The book has nothing to do with war; if anything, it is one individual’s personal victory over his own skeptical detachment. In an author’s note Conrad said he had considered altering the title so as not to mislead readers, but decided against it because he thought Victory was the appropriate title for his story, based on “obscure promptings of that pagan residuum of awe and wonder which lurks still at the bottom of our old humanity.â€

During this past week of “Mission Accomplished†ironies I have thought often of Joseph Conrad and his novel Victory, written before World War I began but not published until 1915. The book has nothing to do with war; if anything, it is one individual’s personal victory over his own skeptical detachment. In an author’s note Conrad said he had considered altering the title so as not to mislead readers, but decided against it because he thought Victory was the appropriate title for his story, based on “obscure promptings of that pagan residuum of awe and wonder which lurks still at the bottom of our old humanity.â€

Do we have some bit of that glimmer of “awe and wonder†in our age of “shock and aweâ€? The one story I read at least once a year is “Heart of Darkness.†“And this also has been one of the dark places of the earth,†Marlow begins his tale. And we know what he means. Wherever we are as we read these words we know the green grass or concrete beneath us covers something in the past dark and bloody. A flight of a few hours can take us to one of several of those dark places. Our “here” can become a dark place overnight. No, Marlow says, the conquest of the earth is “not a pretty thing when you look into it too much.â€

What makes a long-dead writer our contemporary? Why do we feel such a direct connection to a nineteenth century Polish exile and sailor who began writing in English, his third language, after he turned forty? Polish drama critic Jan Kott wondered the same about Shakespeare. In Shakespeare Our Contemporary Kott writes that “Shakespeare is like the world, or life itself. Every historical period finds in him what it is looking for and what it wants to see.†And that is not because Shakespeare foretold things to come, but because, whatever the subject of his story, he filled the stage “with his own contemporaries.†Shakespeare aimed for “a reckoning with the real world.†For Kott, in mid-twentieth century Eastern Europe, it was “the struggle for power and mutual slaughter†in Shakespeare’s history plays that struck a chord. Kott also notes that in Conrad’s Lord Jim, the hero owns one book, a one-volume edition of Shakespeare. “Best thing to cheer up a fellow,†says Jim.

Why do Conrad’s novels and stories resonate with us in our time? Simply because conquest–of those inhabiting the earth, and, the earth itself, in all meridians–IS the story of our times. And, because, damned if they don’t cheer up a fellow like me!

Continue reading Joseph Conrad our contemporary

It’s the end-of-the-week scatter

By the numbers now:

1. Sister city Oregon has its tweakers, we know this because they steal our sculpture and sell it for scrap. (Well, we know it for all kinds of worse reasons, too.) Is it any consolation that we aren’t alone? The city of Brea, California, which has an active public art program, has had three bronze sculptures stolen in the past 18 months. The Wall Street Journal explains the problem as only the WSJ can (at least until Rupert Murdoch makes mincemeat of it): The main component of bronze is copper; three years ago, the price of copper was $1.50 a pound; today, it goes for $4. Walk off with a 250 pound sculpture as thieves did in Brea, and that’s a pretty nice haul.

1. Sister city Oregon has its tweakers, we know this because they steal our sculpture and sell it for scrap. (Well, we know it for all kinds of worse reasons, too.) Is it any consolation that we aren’t alone? The city of Brea, California, which has an active public art program, has had three bronze sculptures stolen in the past 18 months. The Wall Street Journal explains the problem as only the WSJ can (at least until Rupert Murdoch makes mincemeat of it): The main component of bronze is copper; three years ago, the price of copper was $1.50 a pound; today, it goes for $4. Walk off with a 250 pound sculpture as thieves did in Brea, and that’s a pretty nice haul.

A good source for local art theft news? Portland Public Art, a blog that’s a little more various than its title suggests (it takes time out for other sorts of cultural history and is devoted to local indie music), has tracked the theft of Sacagawea in Astoria, for example, and the theft of sculptures by Tom Hardy and Frederic Littman from the Vollum estate. The site also has a rockin’ blogroll, though it’s a little out of date: Art Scatter isn’t on there!

2. Walk in the garden I am still mesmerized by the notion that Sigmund Freud and Gustav Mahler spent four hours chatting together in the Dutch town of Leyden for the express purpose of improving Gustav’s marital, um, relations with Alma. And that Freud decided that Gustav had a mother fixation. Gustav later said that he didn’t agree with Sigmund, but there had been therapeutic benefits in any case. The story pops up in the entry below. They may have even walked through the botanical gardens, at left!

2. Walk in the garden I am still mesmerized by the notion that Sigmund Freud and Gustav Mahler spent four hours chatting together in the Dutch town of Leyden for the express purpose of improving Gustav’s marital, um, relations with Alma. And that Freud decided that Gustav had a mother fixation. Gustav later said that he didn’t agree with Sigmund, but there had been therapeutic benefits in any case. The story pops up in the entry below. They may have even walked through the botanical gardens, at left!

3. Save the past The Guardian newspaper has championed the preservation of artifacts in Iraq. In the latest development Iraqi officials are calling for a world-wide ban on the sale and purchase of Iraqi antiquities, hoping to remove their commercial value to looters, who have stripped 15 percent of the archaeological sites in the country, according to experts. We’ve talked about this before: Whatever your position on antiquities (should they always be returned their country of origin or not), this sounds like a good idea.

In other artifact news: German police uncovered 1,100 pre-Colombian antiquities — Mayan, Incan and Aztec — in a Munich warehouse. Several South American countries are claiming ownership, though a Costa Rican doctor insists that he obtained them all legally. Masks, gems and sculptures were part of the treasure trove. Der Spiegel has the report.

Note on sources: We visit the ArtJournal site every day, as we’ve said before. These stories were aggregated on the AJ site (which contains an impressive list of blogger/columnists as well).

I’ve got the Mahler in me

When tickets to Sunday night’s Oregon Symphony performance of Gustav Mahler’s Ninth Symphony fell my way, the Classical Music Critic’s left eyebrow arched, he peered over his spectacles and with absolutely no edge in his voice to betray him, said, “It’s long.” Long, my brother? Long? I know long. Long is when the stream of time starts to puddle up … and then flow backward, away from me. (Like the Mississippi River after the New Madrid earthquake of 1812.) You look down at your watch and it’s 8:43. Hours pass. Look again and it’s 8:37. Have you been going the speed of light? No, you’ve been in an excruciating play or concert or movie that you can’t escape, a time eddy. Having canoed through these treacherous timestreams before, and survived, “long” does NOT deter me. And the Classical Music Critic, let’s call him Stevie, realized my firm resolve, brought out a reference book that sought to de-mystify the Mahler Nine, from here on known simply as Nine, and improperly prepared, I folded my body into the torture device known as a seat in the Arlene Schnitzer Concert Hall.

When tickets to Sunday night’s Oregon Symphony performance of Gustav Mahler’s Ninth Symphony fell my way, the Classical Music Critic’s left eyebrow arched, he peered over his spectacles and with absolutely no edge in his voice to betray him, said, “It’s long.” Long, my brother? Long? I know long. Long is when the stream of time starts to puddle up … and then flow backward, away from me. (Like the Mississippi River after the New Madrid earthquake of 1812.) You look down at your watch and it’s 8:43. Hours pass. Look again and it’s 8:37. Have you been going the speed of light? No, you’ve been in an excruciating play or concert or movie that you can’t escape, a time eddy. Having canoed through these treacherous timestreams before, and survived, “long” does NOT deter me. And the Classical Music Critic, let’s call him Stevie, realized my firm resolve, brought out a reference book that sought to de-mystify the Mahler Nine, from here on known simply as Nine, and improperly prepared, I folded my body into the torture device known as a seat in the Arlene Schnitzer Concert Hall.

Nine trembles into life as a low, intermittent murmur, conductor Carlos Kalmar motioning to the deepest horns and strings to begin. And immediately Mozart’s Quintet in C Major comes to mind, the contrast of it, that deep cello rising confidently, a growly friction that emerges as a melody of sorts, one of my favorite openings. This is apropos nothing really, though Mahler’s wife Alma recounted that the composer died with Mozart’s name on his lips. (See how we grasp at the slightest biographical evidence to “understand” both what we hear and how we think about what we hear? This thought will escape from parentheses before you know it.) So, low and intermittent, emphasized by plucked notes. Some Mahler analysts claim to detect an irregular rhythm in this, and perhaps it really is there: They say it’s a musical reflection of Mahler’s heart problems, an arrhythmia captured in the beginning of his Death Symphony. (See previous parenthetical!) And then tremulousness subsiding, the heart steady, horns call us to a lush, stringy, sweet orchestral melody, pastoral even.

If we were in a story ballet, the happy shepherd would be gesturing to his happy bride-to-be from a nearby hillock. But this being Mahler, truly, we know this happy harmony will not last, and as I examine my notes afterwards, sure enough:”then darkening and bang we speed along darker, pulsing, too loud for sweet, too brassy, a crescendo and then back to the lush beginning.” In the long first movement, there are serious complications, returns to the melody, more complications. The trombones make a weird, throaty sound, competing musical lines clash and resolve in drumming, the simplest, quietest moment is abruptly overtaken. Sometimes it sound “exotic” like a Conan, to my ears both kitschy and cinematic (more on cinematic later). And then it ends, quietly, fewer and fewer resources of the orchestra invoked, heading for one high, barely audible note.

Continue reading I’ve got the Mahler in me

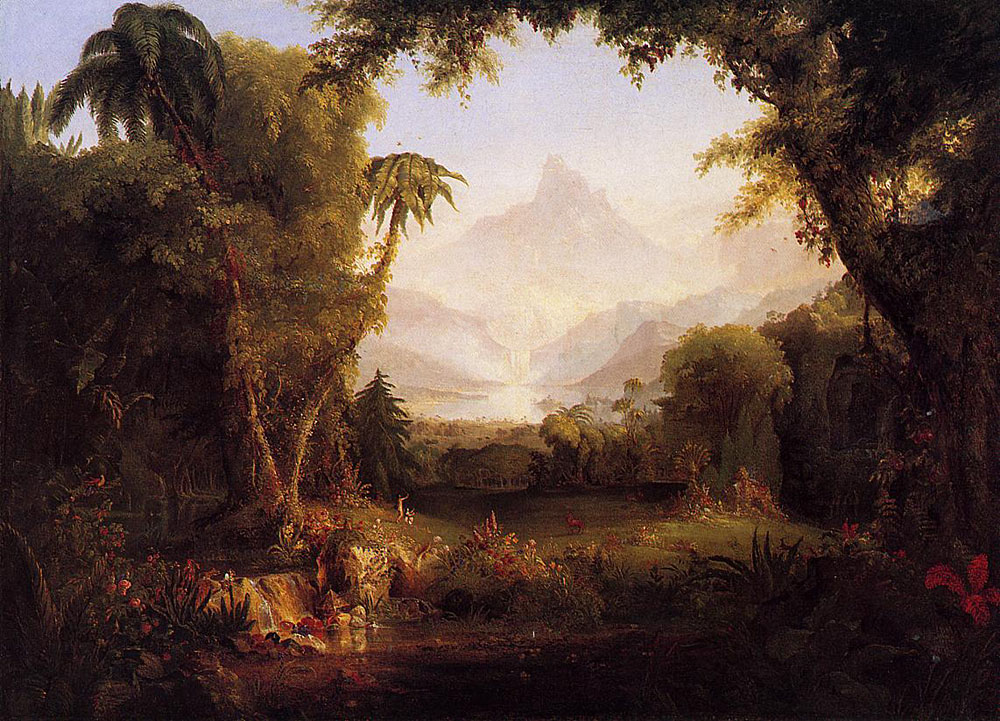

Robert Pogue Harrison: How does your garden grow?

Sickness is not only in body, but in that part used to be called: soul.

Dr. Vigil, in Malcolm Lowry’s Under the Volcano

Portlanders have a garden state of mind. Perhaps even a garden state of “what used to be call: soul.†Forest Park meanders through the city. There are the Japanese and Chinese Gardens and all the micro gardens within their perimeters. In one the “enclosing landscape,†as Edith Wharton put it, is forest, except for a panoramic vista of the city; in the other it is high-rise buildings. There is the highly-ordered Rose Garden and, within its confines, the test gardens that supplied the metaphor for Katherine Dunn’s novel Geek Love. There are community and backyard gardens, porch pots all down the block, and desk overhangs in every office. Yes, our garden varietals are many, to include the world’s smallest, Mill Ends Park, all 452 square inches of it, located at SW Naito Parkway and SW Taylor Street.

But with all the gardens and the countless hours gardening per capita, do we live in a “gardenless age†for lack of really “seeing†the gardens in our midst? Robert Pogue Harrison believes so, and I’m always inclined to suspend judgment and follow the course he charts through art, literature, philosophy, psychology and anthropology – you name it – to the clearing he finds in the woods. I’ve kicked around a bit in his new book, Gardens: An Essay on the Human Condition, but barely have disturbed its topsoil. I’ve spent more time with his earlier books, Forests: The Shadow of Civilization (1992) and The Dominion of the Dead (2003), both remarkable for elegant prose and suggestive argument that draw you back for second and third looks. Harrison takes a ruling image – forests, burials, gardens – and explores how they function in human life and institutions, how they filter through the mind as image and metaphor. What he says about gardens, that they “are never either merely literal or figurative but always both one and the other,†captures his working method in all three books. In Forests, for example, it is the realm of trees that provides the meeting ground of human history and nature, and it too defines “the edge of Western civilization, in the literal as well as imaginative domains.â€

But Gardens is not a primer on “literal” gardens or gardening. Harrison is not a gardener, and I’m not reading his book as one. My husbandry extends to mowing lawn, harvesting dog and cat leavings from the yard, and tending – contemplating – a dead bonsai tree that owns a corner of the porch.

Continue reading Robert Pogue Harrison: How does your garden grow?